Unconscious

An Iceberg Is Not a Good Metaphor for the Mind

It’s time for the iceberg metaphor to melt.

Posted March 1, 2020 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

by Jan De Houwer

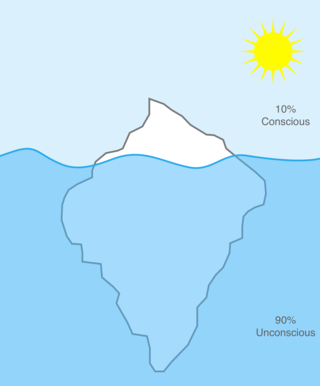

Psychological research has provided abundant evidence for the idea that thinking is not always slow, rational, controlled, and conscious. It can also be fast, irrational, uncontrolled, or unconscious. This idea has inspired numerous applications both within and outside of psychology and formed the basis of the Nobel Prize-winning work of Daniel Kahneman and Richard Thaler. But as is often the case with influential ideas, it has also led to caricatures, one of which is the image of the iceberg mind.

The iceberg mind is an oversimplification in at least two ways. First, it is based on the doubtful assumption that the mind can be neatly divided into two parts or systems that have a range of contrasting features. Whereas the tip of the iceberg is often assumed to represent mental processes that are conscious, effortful, intentional, controllable, and slow, the submerged part stands for mental processes that are unconscious, efficient, unintentional, uncontrollable, and fast. It is generally accepted, however, that these different features do not always nicely align (e.g., mental processes can be unconscious but effortful; see Melnikoff & Bargh, 2018, for a recent discussion). Even if we would divide the iceberg mind only on the basis of one feature (e.g., whether a process is conscious), it is often difficult to draw a clear dividing line (e.g., decide whether the process is conscious or unconscious).

A second simplification that is embedded within the image of the iceberg mind is the idea that the tip of the iceberg (i.e., the conscious mind) is responsible for just a fraction of what we do. This simplification glosses over the important point that conscious thinking probably controls many aspects of our unconscious thinking. Moreover, modern empirical research on unconscious thinking reveals various layers of complexity. For instance, processes that are often regarded as being at the core of the unconscious mind (e.g., implicit bias, conditioning, habits) have been shown to be consciously accessible or to depend heavily on conscious thought (see De Houwer et al., 2019, for an open access review). Rather than suggesting the existence of two separate minds, the available evidence supports the idea of a single mind that shifts between a careful, deliberate mode of operation and a quick-and-dirty mode of operation. This single-mind perspective recognizes that thinking can be fast or slow but focuses on differences in operating conditions (variations in the constraints placed upon a single system) rather than differences in operating principles (distinctions between multiple systems).

Why should we care about all of this? Caricatures such as the iceberg mind have prompted applied researchers to move away from techniques that target the conscious mind (e.g., providing persuasive verbal information) in favor of techniques that supposedly target the unconscious mind (e.g., nudging, habit formation). A single-mind view, however, allows for a much wider range of techniques to change fast, seemingly irrational thinking, including persuasive verbal information. Although behavior change will not result from simply asking people to change their fast or irrational behavior (e.g., asking alcoholics to stop drinking), a change in this type of behavior could be achieved by targeting those beliefs and quick-and-dirty inferences that drive fast and irrational behavior (e.g., training alcoholics to recognize and regulate fluctuations in their beliefs about how harmful drinking is for them; see Hogarth, 2020 , for a discussion).

In sum, although the image of the iceberg mind had merit in communicating the importance of thinking in a fast, irrational, uncontrolled, or unconscious manner, it oversimplifies the nature of the mind and limits our views on changing (fast) behavior. It’s time for the iceberg metaphor to melt.

The author wishes to thank Yannick Boddez for feedback on an earlier version.

References

De Houwer, J. (2019). Moving beyond the distinction between System 1 and System 2: Conditioning, implicit evaluation, and habitual responding might also be mediated by relational knowledge. Experimental Psychology, 66, 257-265.

Hogarth, L. (2020). Addiction is driven by excessive goal-directed drug choice under negative affect: Translational critique of habit and compulsion theory, Neuropsychopharmacology doi:10.1038/s41386-020-0600-8

Melnikoff, D. E., & Bargh, J. A. (2018). The mythical number two. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22, 280–293