Cognition

The Battle of the Bots: Who Wins, Who Loses?

Writing is thinking and thinking is writing.

Posted February 13, 2023 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- AI-generated writing is no substitute for real writing experiences.

- Writing is a complex act that improves all forms of thinking.

- Students who fail to do their own writing are like athletes who refuse to practice.

Like others in my profession of college teaching, I have started to weigh in on the evolving artificial intelligences that can do everything from write a Shakespearean-style play to substitute as a smooth-talking television anchor. From reading news articles, websites, and other sources, my sense is that strong opinions are forming on both sides of the battle of the bots. Many scientists and engineers, business people, and others who view writing as putting a few words down on paper or a computer screen consider it a timesaver from the often arduous task of writing complete sentences and paragraphs to answer generalized questions. In the humanities, including literature and writing courses like the ones I teach, this AI revolution has very real consequences in how we teach and students learn.

Based on my own classroom experiences, I have serious reservations about the new AI writing substitutes for real writing experiences. I am convinced the negative consequences will greatly outweigh the positive influences it will have on actual learning. As every English professor knows, reading and evaluating student writing is one of the most time-consuming responsibilities in our profession. We have all experienced hours of reading student essays and watching the stack of graded papers grow larger and larger on our office desks. Each new essay adds to the ever-expanding pile. Then, suddenly, we realize we are seeing repetitive patterns in phrasing and entire sentences. Soon it becomes apparent that we have read a similar essay, or large sections of an essay, in the graded papers. We stare at the growing stack of graded papers and realize we will have to go through them again, looking for these repetitive patterns in other essays. It cannot be avoided. The integrity of the grading process must be protected so students who are legitimately doing their own writing and thinking are not the ones who are penalized, while others are rewarded.

When more of the same phrasing shows up in already graded papers, it sets off a series of other consequences. Valuable teaching time must be devoted to meeting with each student to discuss the repetitive wording and other signs of plagiarism in their essays. If these meetings reveal that the students are probably not doing their own writing, the instructor is obligated to organize the evidence and present it to a university review committee.

If a professor has 75 students, and even a handful of the essays are suspicious, this brings all other teaching and professional responsibilities to a screeching halt. Professors have an obligation to their universities and the students who do their own writing to follow the process through to its conclusion. Frequently, professors will also find themselves on the defensive unless they have thoroughly researched and found the precise sources for the essays that have suspicious signs of plagiarism.

Over time, it becomes clear that there is only one solution to this problem: professors will decide that all writing will have to be done in the classroom using offline computers or pens and pencils. Only under these supervised conditions is it possible to assure that no artificial intelligence has essentially written the essay. AI has harvested human thoughts and ideas and transformed them into something “original,” only to have some students harvest them from the AI and pretend they are “original” in their essays. In essence, two levels of subterfuge have been created, neither of which is the author’s own work.

But what will this mean for writing as a learning tool, not just a means of communication?

Writing is not just an act of putting letters and words on paper or a computer screen. It is a highly complex process that involves many different cognitive skills that must interact simultaneously to produce thoughts before communicating them. The process of going through these cognitive preliminaries strengthens all other thinking and learning skills. It can be argued that writing, when it involves all the stages in the development of an essay, ultimately leads to more complex thinking patterns that can be applied to other types of problem-solving.

These early stages in the writing process are similar to an athlete who goes through a rigorous training and practice schedule to prepare for the game. If writers allow AI to do all of this work for them, it is comparable to an athlete telling a friend, “You practice for me, but I will play in the game.” The “game,” of course, is the world outside the classroom after the student graduates.

But what happens if all writing is done in class?

Unfortunately, in-class writing does very little to develop these complex skills. Essays that are written over several days or weeks, often while students are engaged in other activities and their brains are mulling over an essay assignment, will inevitably strengthen more complex thinking patterns. This is the “full writing experience,” and the one that will most likely reap benefits for the students in all other areas of academic life and, more importantly, in whatever they choose to do later in their lives.

A few years ago, an international student came into my office and expressed an idea that had occurred to him when he was working on our most recent writing assignment. He said with considerable enthusiasm, “I just realized that writing is thinking.” When I asked him, “How did you come to that conclusion,” he replied, “While I was going through the drafts of my essay.” I congratulated him for his insights, and then he shared more of his evolving thoughts on the essay assignment. It was clear that those thoughts had evolved over several drafts and considerable thinking and rethinking of the essay prompt. The fact that the insight regarding the relationship between writing and thinking came from an international student who was writing in a second language made his observations even more remarkable.

Writing improves thinking, and thinking improves writing. However, this foundation for complex thinking and writing is not possible when artificial intelligence takes over and produces the early—and often the final—thoughts and relationships among ideas. AI will only provide a superficial forum for such interactions.

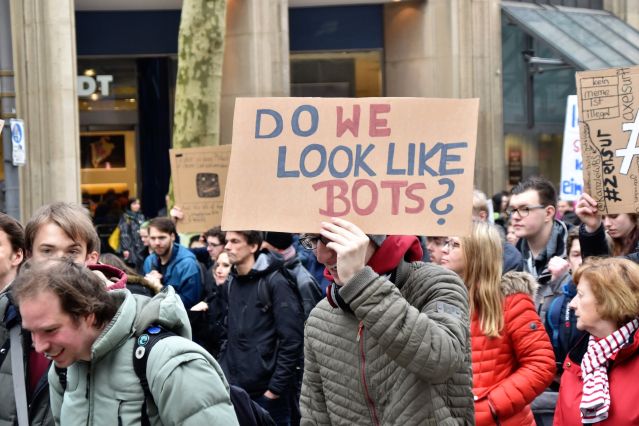

I have read that AI detectors are being developed to detect AI-written documents. Are we reaching the point where most communication will occur between two robotic devices, bypassing the human brain altogether? If so, the gathering dystopian world I have written about in several novels is assuredly overtaking and undermining our common humanity.

I have noticed that many writers are now concluding their op-eds and letters to the editor with a disclaimer regarding their use or non-use of AI assistance. So here is my disclaimer.

Note: This post was not generated by an AI determined to create the impression of impartial thinking and flawless, albeit somewhat stilted delivery of catch-all phrases that sound human, but are delivered by human impersonators without an ounce of real creativity in their soulless computer chips.