Career

How Did a Fake Psychiatrist Work for 20 Years in U.K.'s NHS?

With no qualifications, she posed as a doctor and psychiatrist for two decades.

Posted March 31, 2023 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

How easy is it for someone with no qualifications or formal training to pass themselves off as a properly credentialled therapist? Could a member of the lay public pretend successfully to be a psychotherapist, counsellor, psychoanalyst, or even a psychiatrist?

Does all this confusing terminology contribute to the kind of muddle which may allow fraudsters or hoaxers free reign?

Psychiatrists are medically qualified clinicians who, as doctors, are able to prescribe medication. In many countries, these medics are also signatories on legal documents, such as those depriving the severely mentally ill of their liberty during a compelled admission to hospital.

The widespread public perception is that psychiatrists, because they went to medical school, must inevitably reside somewhere near the "top of the tree," in the hierarchy of public respect and earnings.

Therefore, surely, it is this group of professionals, whose qualifications and training are the least vulnerable to being faked?

That perception becomes threatened by the remarkable and widely reported case in the U.K. of Zohlia Alemi, who has recently been found guilty of fraud and deception. Despite not being qualified as a medical doctor, she apparently worked as a psychiatrist in the National Health Service (NHS) of the U.K. for between 19 and 22 years (estimates vary).

She may even have been on the formal medical register, the key directory of all qualified doctors, for longer.

Alemi’s deception was first exposed by journalist Phil Coleman, working for a local U.K. newspaper, The News & Star, in 2018.

The pretend doctor was first prosecuted for forging the will of a former patient. While working at a community hospital as a locum doctor in 2016, Alemi was arrested and then prosecuted for the attempt to swindle an 84-year-old widow out of her estate.

Her scheme was to inherit the woman’s entire £1.3m, but for the vigilance of a care worker, who supported the pensioner, the fraudster’s attempt was foiled.

After Alemi was prosecuted for that crime in 2018, Coleman uncovered an even deeper dishonesty: that this supposed psychiatrist had never even qualified as a doctor.

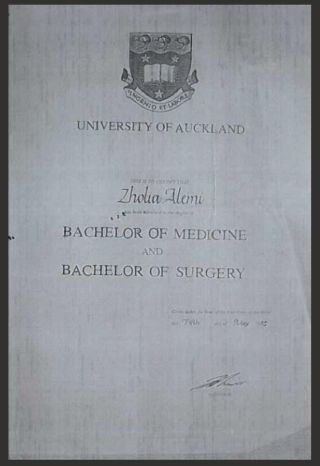

She gained entry to the U.K.’s Medical Register with clumsily forged documents—a degree certificate and a letter of verification from the University of Auckland Medical School, yet with the word "verify" misspelt.

On February 28 2023, as she sentenced 60-year-old Alemi to a seven-year jail term, Judge Hilary Manley, presiding over the case at Manchester Crown Court, highlighted the slapdash quality of the forged documents, which featured poor quality printing, grammatical errors, and blatant spelling errors.

The judge slammed the U.K. regulator of doctors, the General Medical Council (GMC), for an "abject failure of scrutiny," and called for a “thorough, open, and transparent” inquiry into the failings that allowed Alemi to work as a fake doctor and be on the medical register for 22 years. The judge also raised concerns about evidence from a GMC representative during the trial in which the court was told there was a high level of scrutiny of documents.

The judge said the court was "troubled" by the apparent contradiction over a statement from the GMC, which said documents in the 1990s were not subject to the "rigorous scrutiny" now in place.

On the GMC website, the regulator admits it received nine complaints about this 'doctor' from patients during the 23 years that Alemi was on the medical register.

The GMC claims that all these patient complaints were investigated fully by the agency. It remains unclear what sanctions she ever received from the GMC.

Nine patient complaints is quite a large number. This all contributes to the suspicion that patient concerns about doctors are not important to the medical regulator.

It also suggests that, ironically, it may have been patients, not fellow doctors, professionals with years of training, nor even the regulator of doctors, who were able to spot a fake psychiatrist for what they really were.

The judge in the trial questioned why it was a journalist who uncovered Alemi’s deception and not the GMC, suggesting, perhaps, the case calls into question the very point of a medical regulator.

As a psychiatrist, Alemi may have signed Mental Health Act papers depriving patients of their liberty for extended periods of time. Was she also involved in signing paperwork delivering electroconvulsive therapy to patients, despite, it would now appear, not being qualified to do so?

The GMC has apologised for “inadequate” checks and “any risk arising to patients as a result”. But if the GMC can't spot the difference between a real doctor and a bogus one, then they truly are not fit for purpose, as diagnosed by a recent editorial in the British Medical Journal.

The shocking case of Alemi may explain why there is now a growing demand from the public and from doctors in the U.K. to have the GMC replaced by a more responsive and intelligent regulatory authority, as evidenced by the recent popular petition on the Houses of Parliament website calling for a change of regulator for doctors.

The Alemi case, in a sense, resembles a real-life large-scale "experiment", which tests and challenges our beliefs over the vital importance and necessity of qualifications or training in the treatment of mental illness, plus all that bureaucracy that administrates these processes.

The incident echoes a controversial infamous experiment supposedly conducted back in the early 1970s, where, purportedly, eight entirely sane people apparently gained admission to 12 different psychiatric hospitals in the U.S.

The experiment, conducted by David Rosenhan, a professor of law and of psychology at Stanford University, entitled "On Being Sane in Insane Places", has since attracted controversy and criticism, but its influence remains huge, directly contributing to an overhaul of the diagnostic process in psychiatry.

Should the Zholia Alemi incident similarly make us more cautious about the very nature of ‘expertise’ in the worlds of psychology, psychotherapy, and psychiatry?

References

'Judge-led inquiry should examine Alemi fake doctor scandal' By Phil Coleman Chief Reporter https://www.newsandstar.co.uk/news/23356782.judge-led-inquiry-examine-a…

Fake psychiatrist Zholia Alemi who forged medical degree jailed By Phil McCann BBC News https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-lancashire-64797676

Were any complaints made about Zholia Alemi during the time she was practising? https://www.gmc-uk.org/news/news-archive/our-update-on-zholia-alemi/were-any-complaints-made-about-zholia-alemi-during-the-time-she-was-practising

Editor's Choice Accountable to no one, upsetting everyone: the GMC must be reformed Kamran Abbasi, editor in chief BMJ 2022;379:o2700 https://www.bmj.com/content/379/bmj.o2700).

Create a new regulator of doctors to replace the General Medical Council (GMC) https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/629226

On Being Sane in Insane Places D. L. ROSENHAN SCIENCE 19 Jan 1973 Vol 179, Issue 4070 pp. 250-258 DOI: 10.1126/science.179.4070.25