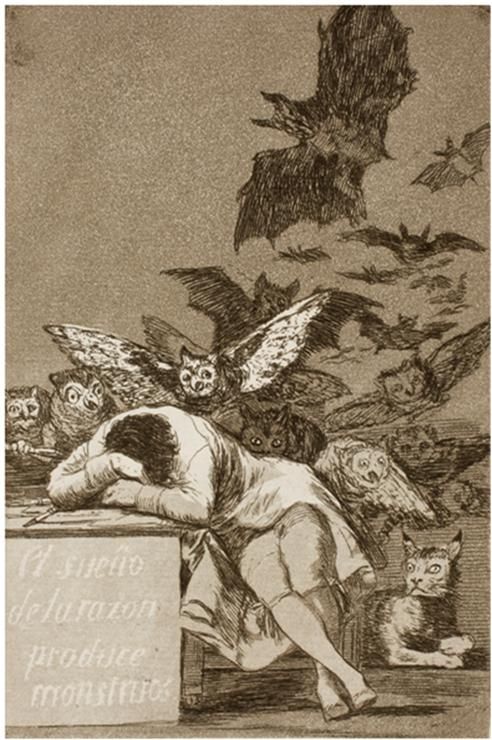

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes, “El sueño de la razon produce monstruos,” British Museum

In previous posts, we covered the dream imagery, sometimes violent, sometimes fantastic, of patients who suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder and narcolepsy. Here, we explore what happens when people physically react to their dreams, and in so doing, harm others or themselves. What normally inhibits these impulses, and what enables them?

“My husband has been punching me in the face in the morning”

The couple in my office were both extremely distressed. The woman had bruises on her face, but she was not the patient. Her husband, a physician and colleague of mine, was the patient. She told me that for several weeks, her husband had been getting up in the morning in a state of confusion and would start to pummel her face. After seconds or minutes, while she was screaming, he stopped the violence but had absolutely no recollection of what had happened or of any dream imagery to which he might be reacting. The woman was not sure whether this was a matter that she should bring to the police or to medical attention. This office visit was early in my career, and I had not encountered this type of problem before. After detailed questioning, I became convinced that my colleague had no criminal intent, but needed immediate medical treatment. I believed that he was demonstrating a form of sleep drunkenness or sleep walking, and prescribed the medication clonazepam, which abruptly reduced these symptoms. The doctor had also been sleep-deprived, which I believed contributed to his abnormal state, and I recommended that he get more sleep. Thankfully, the violence never recurred.

“I was killing my enemies”

In the early 1990s, I saw an older gentleman who had been in combat while in the military many years before. His wife complained that he would jump out of bed and strike at the air with his fists, at times injuring himself when he struck a wall or furniture. The patient would then abruptly awaken and recall that he had been reacting to violent dreams. The dreams involved enemy soldiers who were attacking him with weapons, and he was defending himself. I concluded that this patient was suffering from REM sleep behavior disorder, a condition in which patients react to their dream content. I started him on treatment with clonazepam, and he too did very well on the medication. However, there were nights when he did not use the medication, and the violent activity returned. This lapse, unfortunately, had tragic consequences: one morning he was found dead on the floor after he leapt out of bed and broke his neck.

“I was fighting off animals, maybe wolves”

Another male patient who exhibited violent activity during sleep in response to dream imagery, dreamt of being chased by animals that he could not always identify. His dreams were very realistic to him, with both visual and auditory components. He would awaken after striking a wall in the midst of dreaming that he was fighting off the animals. The animals were indistinct, but he thought they might be wolves.

“It started on our honeymoon”

A man in his 60s, who had been virtually paralyzed from the neck down from a mysterious disease for about 10 years, came to the clinic for a sleep evaluation because he was on a machine that was breathing for him and we needed to check the settings. I had never seen him before, and therefore took a detailed medical history. I was astonished to hear from his wife that his sleep had never been normal, even before he developed the neurological condition that eventually left him paralyzed. She stated that she first noticed abnormalities on their honeymoon, when he would react to violent dreams with yelling, screaming, and punching the air. For safety reasons, they ultimately slept in separate beds, and so, although the symptoms continued, it was not thought to be a major problem. About 20 years later, he started to develop symptoms of a progressive neurological disorder that would leave him paralyzed and dependent on a ventilator to breathe.

“I was being killed by a man wearing a mask”

Violent sleep episodes are not only the purview of men. As I recount in my book, The iGuide to Sleep, a 46-year-old woman and her husband came in to the sleep clinic because she was afraid to fall asleep.

Since childhood, she had a history of bad dreams, and dreaded going to sleep each night because of it. In most of her dreams, she was trying to protect herself from being attacked by a masked man who was trying to kill her with a knife. Her husband had been awakened by her dreams, and observed that she would yell, make fists, and strike out many times. These episodes usually began at about 1:00 in the morning. Besides making fists, she would move her head from side to side as though she was frightened and being hit. Sometimes her husband would waken her during the more severe episodes and hug her until she settled down. Then she would drift off to sleep. Sometimes, during her dreams, she hit her husband “pretty hard,” and he had the bruises to show for it. Because of all this, traveling and staying overnight at other people’s homes was out of the question. Unfortunately, the couple had experienced this trauma for most of their 28 years together.

She had never had any brain injury, infection, or loss of consciousness. She had no history or symptoms of psychiatric disorders. The good news was that I could identify the problem quickly and knew of a treatment that would solve her problem virtually overnight.

Understanding normal sleep

The states of the brain have always been mysterious. In the early 19th century, scientists believed that there were two states—awake and asleep—and the latter was thought to be a form of reversible death. In the middle of the 20th century (in the same year that the structure of DNA was discovered by Watson and Crick), we learned that there were at least three states—awake, asleep, and REM (rapid eye movement) sleep. The latter is when most of our dreaming occurs. All mammals that have ever been studied have REM sleep.

We have since learned, however, that these three states are not uniform. When we sleep and are not in REM sleep, there are different depths of sleep that we can record in a laboratory. Similarly, we know that REM sleep itself is not uniform; there are times when the eyes move and other times they do not. Except for some muscle groups, (sphincters at the top and bottom of the gastrointestinal tract and the major breathing muscles), we are paralyzed throughout REM, and cannot move or react to dream content.

Interestingly, we also know that some parts of the brain can be awake while other parts of the brain are asleep. This is something we learned from marine mammals, who may sleep with one half of their brain awake, allowing them to be vigilant while the other half of their brain is asleep. We have also learned that we do not go directly from being asleep to being wide awake and alert. Rather, there is a transition phase during which some parts of the brain—the area that controls motor activity, for example—rouse before we become mentally alert.

So what went wrong with the above patients?

We believe that the first patient, the doctor who punched his wife, suffered from sleep drunkenness. The part of his brain controlling the muscles “woke up” before the rest of his brain. Such patients are usually not reacting to what they are dreaming and have no recollection of the violent act. This is likely a variant of sleepwalking. Many people vocalize during sleep, often mumbling incoherent words or phrases, and some may yell and scream. The latter symptoms may occur as a manifestation of sleep terrors, a condition in which the patient (most often a child) appears to awaken with a blood curdling scream, face sweating, pupils dilated. These patients don’t recall dreams to which they are reacting. We don’t recommend treating these conditions unless there is a risk of the patient harming themselves or others.

The other patients, however, were reacting physically to what they were dreaming. In their cases, the mechanism that keeps one paralyzed during REM did not work properly. We call this REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. Research conducted in 1965 identified lesions in the nervous system of cats that caused them to react to dream content. It was predicted that humans might develop such a disease, and indeed it was described in humans 21 years later. Although most of the reported cases are older men, it does occur in women and younger adults. Although we usually can’t figure out what causes REM Sleep Behavior Disorder, we know that it can be caused by some medications and can be associated with diseases that result from the production of an abnormal form of a chemical in the brain called synuclein. These neurodegenerative diseases are called synucleinopathies and include Parkinson's disease, Dementia with Lewy Bodies, and multiple system atrophy. What we also now know is that about half of patients with RBD are likely to develop one of these diseases within 10 years.

For reasons that are not well understood, many patients with RBD respond dramatically to the medication clonazepam from the first night they take it. Thankfully, they may never physically react again to the attacking wolves, enemies, or faceless killers.

Reference: Postuma RB, Gagnon JF, Montplaisir JY, REM Sleep Behavior Disorder and Prodromal Neurodegeneration - Where Are We Headed? Department of Neurology, McGill University, Montreal General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada ; Centre d'Études Avancées en Médecine du Sommeil, Hôpital du Sacré-Cœur de Montréal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.