Psychopharmacology

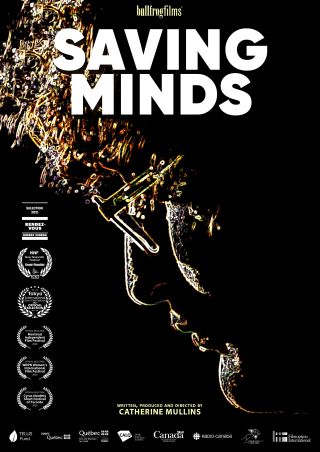

Saving Minds: A Film Review

A powerful new documentary investigates how severe mental illness is treated.

Updated February 29, 2024 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- Forced medication from involuntary hospitalization tends to worsen suffering and long-term outcomes.

- Trying to eliminate all symptoms makes their recurrence appear as relapse and encourages polypharmacy.

- Community care, social integration, and self-affirmation are shown to be viable alternatives.

“When I first met Myriam Anouk,” the narrator shares near the start of Catherine Mullins’ remarkable new documentary Saving Minds (Bullfrog Films 2024), “she was coming to terms with her life after 10 years in the mental health system.”

That deceptively simple sentence turns out to refer to nine hospitalizations in Montréal’s mental health facilities, during which Myriam Anouk (her complete first name) is forced to take medication, told when to sleep and when to get up, and, to all appearances, incarcerated in a high-security jail. Held involuntarily in such a way, she confides, “You have no rights.”

“A High Price to Pay”

What had happened to Myriam Anouk that such “treatment” could be considered appropriate, even an aid to healing and recovery? “Family was important to me,” she confides, “and my mother was my family.” When her mother—a charismatic Québécoise poet—passes, leaving behind her creative works and a legacy of more than 900 poetry readings, her grieving daughter becomes “deeply depressed. I was in mourning. I had no family.”

After such loss, Myriam Anouk entered 9 months of “intense sensations,” involving hours of walking, during which she began to hear voices. “At first I tried to rationalize them away,” she explains with customary precision and self-awareness, but soon there were five or six of them talking at the same time, and they were “very invasive.”

“You’re walking down the street, and someone calls out, ‘Myriam! Myriam Anouk!’ I’d turn around, but no one was there.”

The hospital gardens, where Saving Minds opens, are a place of sanctuary and calm in a setting lacking both. “The few times I came here,” she explains, “I was accompanied by an attendant, in search of an oasis, freedom of sorts, that I didn’t have inside.” Back under involuntary care, she is made “a prisoner again.”

In Search of an Oasis

As Saving Minds revisits what happened to Myriam Anouk, including how similar substandard care has become common across Canada and the United States, the film adds thoughtful expert commentary from psychiatrists, psychologists, psychoanalysts, researchers, fellow patients, and city-wide organizations committed to lessening her suffering so that she can live more freely.

In the case of Myriam Anouk, especially at moments of duress, that means accepting that the voices may return—an outcome some psychiatrists view as a sign of “relapse” and, thus, implicitly, that treatment has failed. (Roger, one of the patients interviewed, explains: “There’s like this attitude where … symptoms must be managed, eliminated at all costs, by any means necessary. Which leads many people to take far too many medications.”)

But is the idea of treatment failure here part of the problem, in that it is driving record amounts of polypharmacy? What if, as for Myriam Anouk, a solution lies in learning to coexist with the voices she hears, rather than using psychiatric drugs or therapy to try to block and suppress them?

With its focus on alternative approaches to severe mental illness, with less reliance on medication, Saving Minds makes clear that in orthodox psychiatric treatment, something has to give way. It may be the patient’s health that does. The system of “care” to which they’ve been entrusted is, after all, involuntary; the medication may at times be forced on those who, under other circumstances, would reject it.

The “Time” of Illness

For Daniel Bordeleau, a doctor, psychotherapist, and Jungian analyst who has treated many suffering from psychosis and severe mental illness, and whose careful listening and deprescribing proves most beneficial in reaching and supporting Myriam Anouk, “We start with the premise that you were unable to tolerate an intolerable situation. You needed an escape. So you entered an altered state. But it’s not a choice one makes.”

After three or four days of sleep deprivation, observes Robert Whitaker, author of Anatomy of an Epidemic, most of us would find that fragility neither extraordinary nor especially difficult to understand. That is one reason he and other commentators, such as Martin Harrow (author of the famous “Chicago study” on antipsychotics and their long-term outcomes) discuss the continued importance of noticing “the ‘time’ of illness,” including the patterns of stress that indicate greatest vulnerability to suffering and illness.

For Bordeleau, biology may be a “bridge” to psychology, but it is not a viable end in itself. For one thing, it leaves too much unexamined and unresolved.

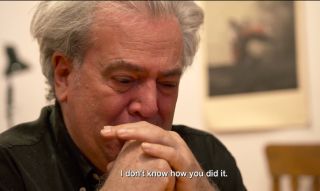

“When someone is experiencing full-blown panic, filled with fear, you must first calm them down. And you use medication for that. Otherwise, you can’t reach them psychologically.” Most of the analytic work involves finding and sustaining a perspective that can tolerate an ever-larger range of pain and happiness—the kind shown in a scene involving Myriam Anouk’s half-brother, whose eyes fill with tears as he recalls one of the times she was hospitalized. (This reviewer’s did as well.)

For the UK psychiatrist Joanna Moncrieff, also interviewed for the film, there is a “high price to pay” for atypical antipsychotics, including a significantly higher risk of heart disease, diabetes, and sexual dysfunction. When prescribed, Moncrieff advises, it should be as a last resort rather than, as common today across mental health, the recommended first-line treatment.

It is a testament to Mullins’ skill in film-making that we are led to care so much about Myriam Anouk’s evolving perspectives on her past, her residual family, her painting and writing, and the way both help her reimagine life in all its psychic complexity.

An Open Mic for Mental Health

In researching Saving Minds, a film tied to a mental health crisis in her own family, Mullins heads to Montréal’s Open Mic for Mental Health, a warm and friendly gathering where people speak freely about their experiences.

There she hears both Myriam Anouk reading her poetry and the stand-up comedy of Alo. Named after the self-healing plant (aloe vera) and a range of greetings in different languages, Alo identifies as nonbinary, is diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and is similarly put on antipsychotic drugs, with mixed results. After several manic episodes that leave them exhausted and suicidal, Alo, too, is hospitalized and spends weeks trying to navigate the city’s resources in hopes of maintaining recovery and resuming their life through comedy.

“I love to perform,” Alo delights in saying, including for the validation an audience can give. Part of their philosophy draws from Steve Martin’s observation that comedy is “the last stand of the ego”—suggesting the place where it is most vulnerable and exposed but, also, for that reason, most amenable to change.

A powerful, moving documentary about the suffering that accompanies severe mental illness, Saving Minds takes us through the promises and pitfalls of several treatment approaches, including antipsychotics and their adverse effects. As elsewhere in our culture, it finds that community support, social integration, and self-affirmation without judgment are more effective and longer-lasting than is the forced, involuntary “care” of the psychiatric hospital.

If you or someone you love is contemplating suicide, seek help immediately. For help 24/7, dial 988 for the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, or reach out to the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741. To find a therapist near you, visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

References

Saving Minds (Green Lion Productions/Bull Frog Films, 2024). Available for screening, classroom rental, and DVD purchase at http://bullfrogfilms.com/catalog/smind.html.