Sex

Are There Sex Differences in Pandemic Leadership?

Sex differences in leadership: Possible evolutionary–developmental origins

Posted May 7, 2021

A Guest Post:

Sex differences in pandemic leadership, and their evolutionary–developmental origins

By Severi Luoto and Marco Antonio Correa Varella

Sex differences in brain, cognition, and behavior are perennially interesting to laypeople and scientists alike. The latest point of contention has revolved around the question of whether female leaders might be more likely than male leaders to save lives during the COVID-19 pandemic, and if so, what causes these sex differences. Here, we take an evolutionary–developmental approach to explaining sex differences in cognition, behavior, and leadership in and out of a pandemic context.

Sex differences in leadership

In a recent article, we reviewed the current evidence around the question of sex differences in pandemic leadership, focusing on the COVID-19 context. We concluded that the strategic circumspection of empathic feminine health “worrier-leaders” has brought more effective and humanitarian outcomes than the devil-may-care incaution of masculine risk-taking “warrior-leaders”. As shown by most of the existing studies, female leaders, on average, reacted more quickly and decisively to the COVID-19 pandemic than their male counterparts, implementing measures that resulted in lower mortality rates (Luoto & Varella, 2021). It is perhaps not a major surprise that the 2020 Ig Nobel prize in “Medical Education” was awarded to a group of male political leaders “for using the COVID-19 viral pandemic to teach the world that politicians can have a more immediate effect on life and death than scientists and doctors can” (Tanne, 2020).

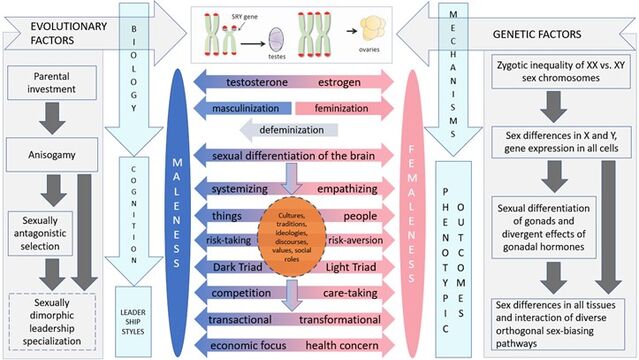

As evolutionary human scientists, it is particularly interesting to us what causes such sex differences in leadership styles and outcomes. We therefore looked at whether sex differences in leadership styles have corollaries in other psychobehavioral traits (more about their causation later). As shown in Figure 1, there are indeed many general psychobehavioral sex differences that align with sex differences in leadership styles.

Research on leadership styles has shown that women, on average, are more communal, intuitive, sensitive, and empathic as leaders than men (Luoto & Varella, 2021). Women tend to exhibit a transformational leadership style which is more relationship-oriented, whereas men tend to show a transactional leadership style which is more task-oriented. Men, on average, tend to prefer having power and being feared, while women tend to prefer gaining others’ respect and being loved. It is these differences in leadership styles, and more general sex differences in psychobehavioral traits, that appear to be reflected in women’s better success at minimizing COVID-19-related deaths (Luoto & Varella, 2021).

Note: Figure 1 outlines possible evolutionary–developmental origins and proximate mechanisms underlying psychobehavioral sex differences, including those in leadership. Sexually dimorphic leadership specialization is included as a new hypothesis, not as an established fact.

Sex differences in personality

Individual variation within each sex tends to be larger than variation between the sexes. For this reason, we depict sex differences as phenotypic continua in Figure 1, which doesn’t divide men and women into two distinct categories but rather shows the maleness–femaleness continuum on a range of sexually dimorphic psychobehavioral traits. Despite within-sex variation and between-sex overlap, numerous studies and several meta-analyses have consistently reported that males and females differ on a range of psychobehavioral traits (e.g., Archer, 2019).

Sex differences in leadership tend to be aligned with sex differences in personality (Fig. 1). For instance, women, on average, have higher scores on empathizing than men. Empathizing refers to the ability to recognize another person’s mental state (“cognitive empathy”) and the tendency to respond to it with an appropriate emotion. Men, in contrast, tend to score higher than women on systemizing, which refers to the tendency to build a rule-based system, to see patterns in systems, and/or to understand how such rule-based systems work. Sex differences in empathizing–systemizing generally range from medium to very large (Luoto & Varella, 2021).

Findings in many areas of research have consistently shown that women, on average, perceive and orient towards people with greater psychological interest, whereas men, on average, are psychobehaviorally more oriented towards objects than women are. Furthermore, men, on average, have higher risk-taking and competitiveness, and lower fear in real-world situations, lower social interests, social leadership, peer attachment, guilt, and emotional intelligence than women (Archer, 2019). Women, in contrast, have higher average levels of anxiety, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism (the tendency to experience negative emotions). These psychological sex differences may lead to women’s higher people focus in pandemic leadership, while male leaders implement riskier short-term decisions perhaps in an attempt to minimize economic disruptions (Luoto & Varella, 2021).

Women have higher pathogen disgust than men both generally as well as in the COVID-19 context (Al-Shawaf et al., 2018; Stevenson et al., 2021), which suggests that women’s decision-making may be more focused on minimizing the spread of a deadly virus than men’s. Women in the general public also showed more concern about their own and others’ health, wearing masks more frequently than men did (Galasso et al., 2020), even though COVID-19 disease severity and mortality are higher in men (Krams et al., 2020). Strikingly, women’s dreams during the pandemic had significantly lower positive emotions and higher rates of negative emotions, anxiety, sadness, anger, body content, and references to biological processes, health, and death than men’s dreams (Barrett, 2020), which indicates that women’s greater health concern and neuroticism extend from their daily lives during the pandemic even to the realm of dreams.

Finally, research into antisocial and benevolent aspects of personality has revealed sex differences in so-called Dark Triad and Light Triad traits. The Dark Triad traits—Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy—may be important in a pandemic context, which calls for coordinated, cooperative, and unselfish action. Machiavellianism is associated with exploitative behaviors, self-interest, and a ruthless lack of morality; narcissism is characterized by a sense of grandiosity, egotism, and self-orientation; and psychopathy entails antisocial behavior, impulsivity, and a lack of empathy and remorse. In contrast, the Light Triad traits—Kantianism, Humanism, and Faith in Humanity—is a complementary set of attributes which predicts prosocial rather than antisocial attitudes and behaviors (Kaufman et al., 2019). Kantianism refers to treating people as ends unto themselves; Humanism is characterized by valuing the dignity and worth of others; and Faith in Humanity refers to believing in the fundamental goodness of humans. Women tend to score higher on the Light Triad traits, while men, on average, have slightly higher scores on the Dark Triad personality traits.

In the aggregate, these psychological sex differences may mean that cautious, humanitarian responses come more naturally to female leaders, while male leaders may be more concerned with retaining the integrity of the socioeconomic system, which in some cases has led to jeopardizing population health during the COVID-19 pandemic (Luoto & Varella, 2021).

Evolutionary–developmental origins of sex differences

Psychobehavioral sex differences ultimately arise from sexual selection, sexual differentiation of the mammalian brain, sexual division of labor, and their interactions (Fig. 1). Sexual selection and sex differences in parental investment have shaped status-striving and power-seeking among men more than in women, resulting in (sometimes violent) competition, risky economic pursuits, and men taking on more leadership positions than women, particularly at higher organizational and societal levels. The mammalian pattern of inter-male competition arises partially because fertile females are a limiting resource for male reproduction, which generally leads to higher risk-taking and status-seeking in males relative to females.

Evidence of overt sex‐biased treatment by others (equivalent to what social constructionists think of as socialization into gender roles in humans) is lacking in many species of non-human animals. In the few species that have been studied, little to no difference has been found in behaviors of mothers towards female and male offspring (Lonsdorf, 2017). Nevertheless, such species show sex differences in behavioral development that resemble differences found in infant humans.

Furthermore, an analysis of 76 non-human mammal species (Smith et al., 2020) found that female-biased leadership occurred only in eight species: bonobos, ring-tailed lemurs, black-and-white ruffed lemurs, killer whales, spotted hyenas, African lions, African bush elephants, and Asian elephants (Smith et al., 2020). Male-biased leadership is therefore not limited to human societies but is also found across the mammalian lineage.

While some hold the position that socialization into gender roles causes sex differences in humans, this hypothesis is generally not supported when considering the biological, developmental, neuroscientific, and cross-national evidence more broadly (Archer, 2019; Luoto & Varella, 2021). Since evolutionary processes pre-date social conceptualizations of gender roles by several million years, a complete explanation of the interplay between social conceptions of gender roles and evolved biological predispositions would need to account for how evolutionary processes act as precursors to gender roles—a question for which evolutionary psychology provides a plausible multilevel explanatory framework (Archer, 2019; Luoto & Varella, 2021).

During critical periods of development in fetal and neonatal life, testicular secretions have permanent effects on the brain, driving sexual differentiation of the brain. There are three major classes of proximate sex-biasing factors: sex chromosome effects (the differential action of X and Y genes), and organizational and activational effects of gonadal hormones. Unlike activational effects, the early organizational effects of gonadal hormones are considered irreversible, creating various degrees of masculinization in brain, physiology, cognition, and behavior (Fig. 1).

The sexually dimorphic leadership specialization hypothesis

Given the stability, universality, and phylogenetic inertia of the sex-typical traits listed above, it is possible to infer that women’s leadership success during disease outbreaks would, because of the same sex-typical psychobehavioral characteristics, also have existed during ancestral times. After all, humans have an evolved leadership psychology, and this sex-specificity could be a part of it. There are indirect findings supporting this sex differentiation in dealing with different kinds of threats in relation to leadership, which we have discussed in detail in our full article (Luoto & Varella, 2021).

Based on such findings, we derived the sexually dimorphic leadership specialization hypothesis, which suggests that it would have been more effective to have male community leaders during ancestral (and recent) times of frequent wars, intergroup and intragroup aggression, and possibly during geological and other natural hazards, while during disease outbreaks and famines it would have been more effective to have female leaders (Luoto & Varella, 2021). This possible sex-specific specialization would result from the coevolution between male and female roles as leaders in which men’s and women’s psychological strengths were recurrently recruited by societies and/or followers and used for leadership in different and correspondent threat contexts based on the effectiveness of leadership outcomes in each context.

As such, the sexually dimorphic leadership specialization hypothesis is consistent with how sex differences in parental investment and mating competition have coevolved with parental care specialization. Evolutionarily, parental investment consists of two or more distinct activities: provisioning and defense. Parents may care more efficiently if they specialize in a subset of these activities when it is inefficient for a single parent to provide multiple types of care. This kind of parental care specialization occurs in many taxa (Luoto & Varella, 2021). Based on what is known on psychobehavioral sex differences and their evolution in humans, the sexually dimorphic leadership specialization hypothesis extends models on the evolution of parental care specialization to leadership types.

The sexually dimorphic leadership specialization hypothesis leads to the prediction that women, feminine individuals, or female-biased or feminine coalitions would be more motivated than their more masculine counterparts to help save lives during disease outbreaks, resulting in more effective societal responses. Convergent evidence from hunter-gatherers and large-scale post-industrial societies tends to support the sexually dimorphic leadership specialization hypothesis (Luoto & Varella, 2021). However, the hypothesis still needs to be directly tested using a variety of methods and contexts—and we do not rule out the hypothesis that sex differences in leadership are merely a coincidental byproduct of more general psychological sex differences which evolved for purposes other than leadership.

Author Bios

Dr Severi Luoto: PhD from The University of Auckland in 2020. Evolutionary scientist whose research encompasses diverse topics in evolutionary-developmental psychology, biological psychology, cultural evolution, cognitive psychology, psycholinguistics, behavioral neuroscience, evolutionary biology, and evolutionary-developmental origins of health and disease.

Dr Marco Antonio Correa Varella: PhD from University of São Paulo in 2011. Dept. of Experimental Psychology, Institute of Psychology. Researcher in evolutionary behavioral genetics, evolutionary aesthetics, and evolutionary psychology.

Key Points: Gender differences, leadership, masculinity, femininity

References

Al-Shawaf, L., Lewis, D. M. G., and Buss, D. M. (2018). Sex differences in disgust: Why are women more easily disgusted than men? Emot. Rev. 10, 149–160. doi:10.1177/1754073917709940.

Archer, J. (2019). The reality and evolutionary significance of human psychological sex differences. Biol. Rev. 94, 1381–1415. doi:10.1111/brv.12507.

Barrett, D. (2020). Dreams about COVID-19 versus normative dreams: Trends by gender. Dreaming 30, 216–221. doi:10.1037/drm0000149.

Galasso, V., Pons, V., Profeta, P., Becher, M., Brouard, S., and Foucault, M. (2020). Gender differences in COVID-19 attitudes and behavior: Panel evidence from eight countries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 27285–27291. doi:10.1073/pnas.2012520117.

Kaufman, S. B., Yaden, D. B., Hyde, E., Tsukayama, E., Austin, E., and Kaufman, S. B. (2019). The Light vs. Dark Triad of personality: Contrasting two very different profiles of human nature. Front. Psychol. 10, 1–26. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00467.

Krams, I., Luoto, S., Rantala, M. J., Jõers, P., & Krama, T. (2020). Covid-19: Fat, obesity, inflammation, ethnicity, and sex differences. Pathogens, 9(11), 887. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9110887

Lonsdorf, E. V (2017). Sex differences in nonhuman primate behavioral development. J. Neurosci. Res. 95, 213–221.

Luoto, S. & Varella, M. A. C. (2021). Pandemic leadership: Sex differences and their evolutionary–developmental origins. Front. Psychol. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.633862

Smith, J. E., Ortiz, C. A., Buhbe, M. T., and van Vugt, M. (2020). Obstacles and opportunities for female leadership in mammalian societies: A comparative perspective. Leadersh. Q. 31, 101267. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.09.005.

Stevenson, R. J., Saluja, S., and Case, T. I. (2021). The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on disgust sensitivity. Front. Psychol. 11, 600761.

Tanne, J. H. (2020). Donald Trump, Boris Johnson, and other leaders win Ig Nobel awards for teaching people about life and death. BMJ 370, m3675. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3675.