Sex

Can We Trust What Men and Women Reveal on Sex Surveys?

Not completely. But ample evidence suggests there's value in their responses.

Posted July 11, 2017

Sometimes men and women appear to lie (at least a little bit) when they answer questions on sex surveys. Who can blame them? Why would people reveal their deepest, darkest sex secrets to a complete stranger? Would you?

Still, when surveyed in the proper manner (such as responding in private to well-crafted questions, with clear instructions, and anonymously without anyone ever knowing your name), people tend to self-report at least somewhat honestly about sensitive topics like sex, drug use, and criminal behavior. Fortunately for those interested in advancing sexual diversity science, several evidence-based avenues are available for telling how much people are lying (or not) on sex surveys. Let's take a look at some of that evidence.

What is Your Number?

Perhaps the most compelling evidence people do lie on sex surveys comes from responses to one's “past number of sex partners.” Typically, heterosexual men report slightly higher numbers of past sex partners than heterosexual women do. Assuming a closed-population of heterosexuals, this doesn't really add up. Somebody's probably lying in their survey responses, but it remains to be seen whether the lying comes from men, women, or both.

Actually, though, when it comes to sex differences in past numbers of partners, some evidence suggests people aren't lying at all. How can this be? Researchers have targeted three main explanations why this seemingly impossible sex difference might not involve active lying:

1) Sex Differences in Counting Strategies. When asked about one's number of past sex partners, women tend to enumerate or recall each and every past partner individually (Bill, Ted, Tony, Tim...), whereas men tend to "guesstimate" or give a rough approximation using large round numbers (around 10). Studies looking into this counting-related phenomenon have found when you insist men and women use the exact same counting strategy (everybody counts each one, or everybody guesstimates), the sex difference tends to disappear (Brown & Sinclair, 1999; Mitchell et al., 2018).

The sex difference is also reduced when asking about shorter time frames, such as sex differences in the past year (implicating elaborated counting-strategies as a likely culprit; Brown et al., 2017). Indeed, in a recent study Brown and his colleagues (2017) found sex differences in past numbers of sex partners were primarily present in response to telephone interviews (not on web-based surveys where people have more time to answer), and were only present for those with high numbers of past partners (again, implying that elaborated counting strategies are a cause). Maybe people aren't really lying, after all.

2) Sex Differences in What Counts as "Sex." Other studies have found men and women fundamentally differ in what counts as “having sex” (Wiederman, 1997). Because men consider more sexual behaviors to count as sex than women (e.g., oral sex, intimate massages), this might lead men to report, on average, higher numbers of past sex partners than women do.

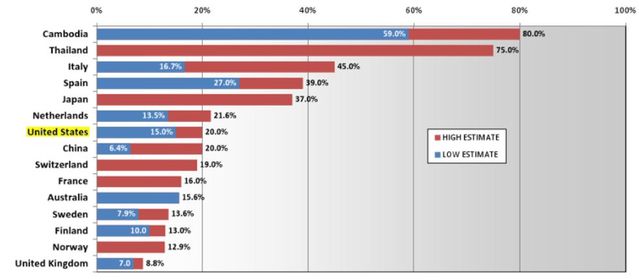

3) Sex Differences in Paying for Sex. Because sex workers are not sampled in most sex surveys (psychologists tend to fail to include them in their research samples), and vastly larger numbers of men pay for sex than women do (about 15 percent of men in USA [see chart below]; versus less than 1 percent of women; Smith, 1998), this might make it seem like men, on average, have more past sex partners than women do (Wiederman, 1997). A study by Brewer and colleagues (2000) found once the undersampling of sex workers and their very high numbers of previous sexual partners is accounted for in large representative surveys of the USA, "the discrepancy disappears."

Given pretty solid evidence of sex differences in counting strategies, what counts as sex, and payments to sex workers, perhaps men and women aren't willfully lying all that much about past numbers of sex partners. At least for the "past number of sex partners" question on sex surveys, maybe men and women just agree to disagree, so to speak. No deception required.

So, Can We Trust What People Report on Sex Surveys?

Short answer: No. In my view, there should be no trusting when it comes to people's responses to questions about sex. Scientists aren't supposed to trust, they're supposed to skeptically and rigorously verify. So, conclusions about the veracity of survey responses to sex questions should depend on the best available evidence, not on ideological beliefs or what we privately think about people's tendencies to lie (or not) about sex.

Shoot, all responses to self-report surveys (whether about sexual behaviors, personality traits, personal values, or preferences for paper plate brands) should be empirically evaluated for their ability to generate useful knowledge. And one of the best ways to rigorously test whether self-reported responses (and scales formed from responses) are truthful is to formally examine the scale's psychometric properties.(Haeffel & Howard, 2010; Nunnally, 1978)

Using the best available tools, researchers have documented sex survey responses are more truthful when demonstrating psychometrically sound levels of:

a) Internal Reliability (people are consistent across many different responses asking about sex; e.g., they don't say they love casual sex on one question, and then later in the survey say they hate casual sex),

b) Temporal Reliability (people responses are consistent in what they say over time about sex; e.g., if they love casual sex today, they probably should also say they love casual sex if you ask them next week),

c) Invariant Factor Structure (people's responses about sex cluster together in meaningful ways; e.g., questions about casual sex should relate to each other in ways that seem to make sense),

d) Content Validity (people's responses about sex include relevant and representative items for all areas of sex we are interested in; e.g., did we ask about the really important aspects of casual sex, and about all the different kinds of casual sex),

e) Criterion-Related Validity (people's responses about sex concurrently correlate with external outcomes we are interested in, and predictively correlate with future outcomes; e.g., do their attitudes to casual sex properly relate to certain sex-linked biological features [e.g., genes, hormones, or brain structure variations], or how they react in a laboratory experiment about casual sex, or predict whether they engage in casual sex over the next year [e.g., self-reported mate preferences for traits such as attractiveness and status actually do predict who people end up with as partners over time; Gerlach, Arslan, Schultze, Reinhard, & Penke, 2019),

f) Convergent Validity (people's responses about sex correlate with other similar sex-related measures; e.g., answers to casual sex questions from measures of erotophilia should strongly correlate with answers to casual sex questions from measures of sociosexuality),

g) Discriminant Validity (people's responses about sex are not correlated with things like response biases; e.g., answers to casual sex questions should not be strongly associated with tendencies to lie on surveys; for instance, in one study the correlation between men's self-reported penis size and social desirability bias was quite small, but it was positive, r(164) = .16, p = .04; King et al., 2019).

There's a lot more to psychometrics than just what I've listed above, but you probably get the idea. Sexual scientists have spent decades trying to develop good sex questions (and scales created by combining responses from several sex questions), so that responses to those questions yield psychometrically sound information.

Not everyone's responses to sexual questions are entirely truthful, of course. Neither are people's responses to questions about drug use, criminal behavior, and many socially sensitive topics. Self-report survey responses can be biased due to lying, limitations of self-knowledge, misunderstanding certain words, and more (Shrout et al., 2017). Even so, psychometric evidence suggests there is enough truth revealed by many self-reported sex surveys to make them scientifically useful. Let's look at an example of a psychometrically sound self-report measure of sexuality.

Evidence of the Usefulness of Self-Reported Sexuality: Sociosexuality

Sociosexuality refers to the willingness to have sex without high levels of commitment (Simpson & Gangestad, 1991). Some people report that they are "high" in sociosexuality (e.g., agree that sex without love is OK), and some people describe themselves as "low" in sociosexuality (e.g., report they must truly love someone in order to have sex with them). Most studies have found men report they are much higher in sociosexuality than women (i.e., more willing to have sex without love or commitment; Schmitt, 2005). But can we be sure? What is the evidence that men's and women's responses to questions about love and sex are truthful? And that men and women really are different in sociosexuality?

Psychometrically, one measure of sociosexuality, the Sociosexual Orientation Inventory (SOI), has been found to possess good levels of internal reliability, temporal reliability, invariant factor structure (especially the SOI-R), content validity, criterion-related validity, convergent validity, and discriminant validity (Simpson & Gangestad, 1991; Simpson, 1998; Simpson et al., 2004). So, based on quite a bit of empirical evidence, responses to this sex survey appear to be real and scientifically useful.

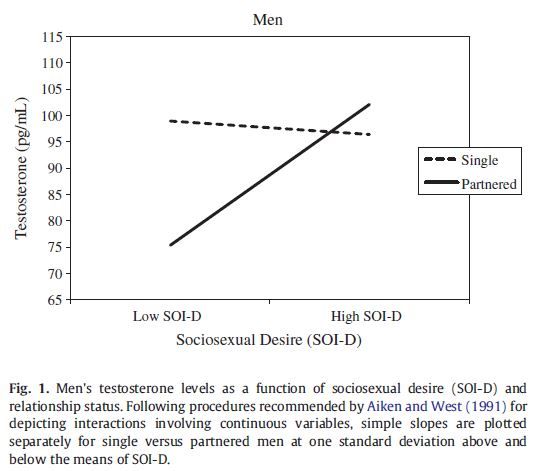

As an example of good psychometrics, self-reported sociosexuality triangulates with information across observers. SOI responses have been correlated with both observer reports and peer ratings, for instance (Gangestad & Simpson, 2000; Simpson, 1998; Simpson et al., 2004). Across numerous studies, SOI responses also are related to external criteria such as facial symmetry, finger length ratios, and hormones (Edelstein et al., 2011; Gangestad & Simpson, 2000; Simpson, 1998; Simpson et al., 2004). For example, being partnered (in a long-term relationship) normally reduces testosterone levels in men, but not among those partnered men who report on self-reported sociosexuality surveys that they still have desires for uncommitted sex (Edelstein et al., 2011).

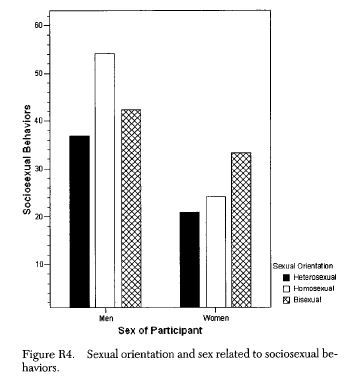

One can also compare gay men to lesbians to get purer estimate of sex differences in sociosexuality (where behavior is not constrained by the opposite sex). Gay men tend to self-report more unrestricted sociosexuality, engage in more extra-dyadic sex, and relax their short-term mate preferences more than lesbians do (Bailey, Gaulin, Agyei, & Gladue, 1994; Buss & Schmitt, 2011; Schmitt, 2005; Symons, 1979).

Lots of studies confirm these findings on sociosexuality. For example, Blumstein and Schwartz (1983) found that 76 percent of gay couples had experienced an affair, whereas only 11 percent of lesbian couples had. Bell and Weinberg (1978) found that 75 percent of gay men have had more than 100 sex partners, with 18 percent claiming to have had more than 1,000 partners (while no lesbians claimed this number of short-term sex partners).

More recently, as noted by Schmitt (2005), gay men have been shown to have identical levels of unrestricted sociosexual attitudes compared to heterosexual men, but because their mating pool consists of other men who possess relatively unrestricted sociosexuality, gay men tend to behaviorally engage in more short-term mating than heterosexual men (see chart below).

SOI responses almost always display convergent validity, relating as theorized with individual difference measures of mating motives, mate preferences, relationship initiation, relationship interaction, and early family environments (Simpson et al., 2004).

Another important tool to make sure self-reported sociosexuality is useful is to dig deep into response biases and demonstrate the SOI has discriminant validity. Schmitt (2005) looked at the response bias of impression management associated with dozens of sex-related measures and typically both men’s and women’s responses are just about equally effected (with lower levels of sexuality associated with higher impression management; but the size of sex differences was largely unaffected when controlling for impression management).

With sociosexuality as measure by the SOI, typically both women's AND men's sexual desires are reduced when controlling for impression management. The sex difference gets slightly smaller, but it is not eliminated by any means. Sex differences in sociosexuality in the USA are reduced from d = .63 to d = .57 after controlling for impression management. About a 10 percent reduction in the size. Not explained away by any means.

So yes, a wide range of evidence confirms the validity of self-reported sex differences in sociosexuality, with men reporting higher levels of sociosexuality than women across all studies ever conducted (Schmitt, 2005; average d = 0.74). We cannot know for certain that every single person is telling the truth to every question on the SOI (they almost certainly are not). But that doesn’t mean the information provided is useless. The best psychometric evidence we have suggests survey responses on the SOI and many other sex-related measures are scientifically useful, and reasonably close to the “truth” when asked in the right way (Andersen & Broffitt, 1988; Catania et al., 1990; Weinhardt et al., 1998).

Cross-Cultural Tests of Sex Survey Responses

Another tool for evaluating whether self-reported sex survey responses are truthful is to look across cultures with different levels of patriarchy. Because of some society's sexual double standards (SDS; the social values wherein men are rewarded for having higher sexual drives, urges, and behaviors, but women are punished for expressing their desires), men and women may present themselves in socially-desirable ways that make us think there are sex differences in sexuality. In reality, these patriarchal double standards may be leading to false impressions. Sex differences in self-reported sexuality may be science's version of fake news.

Frankly, there's quite a bit of empirical evidence suggesting the SDS no longer exists in the USA (Marks & Fraley, 2005; Milhausen & Herold, 1999) and may have even reversed (Howell et al., 2011; Papp et al., 2015). Still, if the classic patriarchal form of the SDS does exist in some cultures, it leads us to expect men are lying on sex surveys by over-reporting their sexual desires, whereas women are lying by under-reporting their sexual desires, and that these lying tendencies will be strongest in the most patriarchal cultures.

Richard Lippa’s (2009) famous BBC study of more than 50 nations is relevant here. Lippa found sex differences in sexual desire were not larger in more patriarchal cultures (as would be predicted by sexual double standards). There’s basically no relationship between the size of sex differences in sexual desire and degree to which men and women are free to be who they want to be, “For both sex drive and height, sex differences were extremely consistent across nations and they were not moderated by gender equality or associated with economic development.” (Lippa, 2009; p. 647) So, this might suggest that women feeling oppressed or constrained in how they report their sexuality does not drastically affect sex differences in self-reported sexuality (at least for sexual desires).

In a separate cross-cultural study of more than 50 nations, Schmitt (2015) found sex differences in responses to the statement, "I can imagine myself being comfortable and enjoying ‘casual’ sex with different partners” were largest in nations with most egalitarian sex role socialization and greatest sociopolitical gender equity (i.e., the lowest levels of patriarchy, such as in Scandinavia). This is exactly the opposite of what we would expect if patriarchy, sex role socialization, and sexual double standards are the prime culprits behind sex differences in self-reported sexuality (at least for casual sex attitudes).

Overall, it seems sex differences in sexual desires and attitudes are not the false result of patriarchy, sex role socialization, and sexual double standards. Sex differences in sexuality appear to be very real, and men and women responding to sex questions in different ways reveals some important truths about human nature. There are additional converging lines of evidence to this effect, actually. Many involving "tricky" experimental designs.

Additional Converging Lines of Evidence on the Usefulness of Self-Reported Sexuality

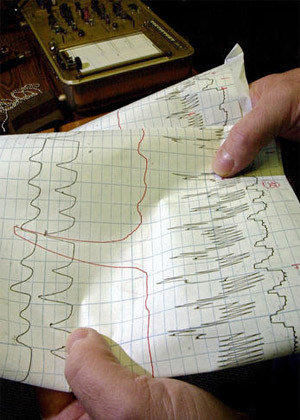

There are several "tricky" techniques that have been used to evaluate (and improve) the truthfulness of sex survey responses (Ó Ciardha, Attard-Johnson, & Bindemann, 2017). One is called the bogus pipeline procedure. Alexander and Fisher (2003) did a “bogus pipeline” study using three experimental conditions: 1) hooking people up to a (fake) lie detector and having them complete sex surveys (the lie detector was intended to elicit the highest levels of truthfulness), 2) having people complete sex surveys anonymously (which is what all sex researchers should do, by the way), or 3) having people complete sex surveys with a researcher conspicuously in the room when they were non-anonymously asked about sexuality (lowest truthfulness expected here, of course).

Sex differences in sexual attitudes (as measured by the Sexual Opinion Survey—a basic measure of erotophilia) remained significant across all three testing conditions. Sex differences were largest in the non-anonymous condition (d = .71). Crucially, the size of the sex difference remained stable across the anonymous (d = .37) and lie detector conditions (d = .36). This result confirms responses to sex surveys under anonymous conditions are as valid as when administered under a lie detector condition. So, sex differences in sexual attitudes do not "disappear" from view when men and women are presumably more likely to tell the truth. They are the same as when people are given true feelings of anonymity when completing sex surveys (which most sex researchers know to do; Robertson et al., 2017).

In a more recent bogus pipeline study (Fisher & Brunell, 2014), sex differences in sociosexuality were very large in the non-anonymous condition (d = 1.22), and strangely were even larger in the anonymous condition (d = 1.32). This result is really weird, and leads me to wonder about their data (I've collected data on sociosexuality from over 60 nations for more than 20 years, never once have I seen a sex difference d = 1.32 on sociosexuality; Schmitt, 2005)1.

Fisher and Brunell (2014) did find more moderately sized sex differences in the bogus pipeline condition (d = 0.60; about what I find in anonymous conditions in a worldwide sample, d = 0.74; Schmitt, 2005). Again, the key point here is sex differences in self-reported sexuality do not "essentially disappear" from view when men and women are presumably more likely to tell the truth. Any claims to the contrary are demonstrably false, based on the best available evidence.

Another "tricky" technique to evaluate the truthfulness of sex survey responses is to have people randomly respond to either a sex question or some other question for which we know the response rate. Because people completing the survey know their responses are truly anonymous and random (there is no way the experimenter can know whether a particular person answered the sex question or the other less sensitive question), we can get better estimates on how truthful people are about sex questions (and they are generally truthful; De Jong et al., 2015; Tu & Hsieh, 2017; Zimmerman & Langer, 1995). This is not to say that self-reported sexuality is always perfectly measured, as there are many challenges and limitations with self-report as a research method (Engeler & Raghubir, 2017; Graham et al., 2003; Harrell, 1985; Langhaug et al., 2010; Minnis et al., 2009; Scandell et al., 2003; Turner et al., 1997). Even so, a lot of sexual science confirms that self-reported sexuality scales can be psychometrically sound and scientifically useful (especially when administered anonymously; see Robertson et al., 2017).

Conclusion: Self-Reported Sexuality is Scientifically Useful (and Mostly Truthful)

Overall, I think the old claptrap arguments that "everybody lies on sex surveys" and “self-reported sexuality is not useful” just don’t stand up to empirical scrutiny. Self-reported sexuality of men and women often has good psychometric qualities, especially if the questions are well-designed and the survey is administered well (e.g., anonymously; Andersen & Broffitt, 1988; Dare & Cleland, 1994; Durant & Carey, 2000, 2002; Fenton et al., 2001; Hamilton & Morris, 2010; Koss & Gidycz, 1985; McCallum & Peterson, 2012; McGahuey et al., 2000; Robertson et al. 2017).

Of course, not every psychological attribute is measured equally well using self-report methods. Historically, self-reported intelligence has only a weak positive association (correlation of about .2) with objectively tested intelligence (Paulhus et al., 1998). More recently, researchers have found these associations are actually higher, with men (.61) being a little more accurate than women (.48) in estimating their own intelligence (Dahl, 2009). Still, not every aspect of ourselves is totally knowable to ourselves.

For instance, people are relatively poor at knowing the underlying reasons why they do things (e.g., motivations for why they cheat). Social psychologists often have this drilled into their graduate training, especially the classic Nisbett and Wilson article (1977). Fair enough, but this shouldn't lead to a jettisoning of the entire self-report baby with the motivational bathwater.

If you ask about what people generally do (e.g., the trait of regularly cheating on their partner), their self-reported answers are rather reliable and valid. Moreover, if you want to know their preferences (I would prefer an open relationship), desires (I want to cheat with several partners), or attitudes toward sexuality (I believe cheating is OK), self-report is even better at obtaining psychometrically reliable and valid information. One of the biggest predictors of someone behaviorally having an affair is whether they self-report having the attitude…"having an affair is OK.” (Treas & Giesen, 2000)

In the end, ample research suggests responses to sexuality surveys are scientifically useful (and mostly truthful). Some self-reports are more useful than others, of course, but that's a matter of rigorous evidence to decide. Blanket disbelief in the value of all self-reported sexuality does real harm to sexual diversity science. Such an ideology should be discarded, don't you think (circle one)?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Not Somewhat Moderately Completely

Discarded Discarded Discarded Discarded

Footnotes

1 Fisher and Brunell (2014) used the SOI-R (Penke & Asendorpf, 2008), possibly accounting for the rather large sex differences they observed in sociosexuality.

References

Alexander, M. G., & Fisher, T. D. (2003). Truth and consequences: Using the bogus pipeline to examine sex differences in self‐reported sexuality. Journal of Sex Research, 40, 27-35.

Andersen, B. L. & Broffitt, B. (1988). Is there a reliable and valid self-report measure of sexual behavior? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 17, 509–25.

Brown, N. R., Schweickart, O., Sinclair, R. C., & Moore, S. E. (2017). Multiple partners, multiple strategies, multiple causes. Cognitive Development from a Strategy Perspective: A Festschrift for Robert Siegler.

Brown, N. R., & Sinclair, R. C. (1999). Estimating number of lifetime sexual partners: Men and women do it differently. Journal of Sex Research, 36, 292-297.

Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (2011). Evolutionary psychology and feminism. Sex Roles, 64, 9-10. doi:10.1007/s11199-011-9987-3

Catania, J. A., Binson, D., Canchola, J., Pollack, L. M., Hauck, W., & Coates, T. J. (1996). Effects of interviewer gender, interviewer choice, and item wording on responses to questions concerning sexual behavior. Public Opinion Quarterly, 60, 345-375.

Catania, J. A., Gibson, D. R., Chitwood, D. D., & Coates, T. J. (1990). Methodological problems in AIDS behavioral research: influences on measurement error and participation bias in studies of sexual behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 339.

Dahl, D. (2009). Self-assessed intelligence in adults: The role of gender, cognitive intelligence and emotional intelligence. Canadian Journal of Career Development, 8(1), 32-38.

Dare, O. O., & Cleland, J. G. (1994). Reliability and validity of survey data on sexual behaviour. Health Transition Review, 93-110.

De Jong, M. G., Pieters, R., & Stremersch, S. (2012). Analysis of sensitive questions across cultures: An application of multigroup item randomized response theory to sexual attitudes and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103, 543.

Durant, L. E., & Carey, M. P. (2000). Self-administered questionnaires versus face-to-face interviews in assessing sexual behavior in young women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 29, 309–322.

Durant, L. E., & Carey, M. P. (2002). Reliability of retrospective self-reports of sexual and nonsexual health behaviors among women. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 28, 331–338.

Edelstein, R. S., Chopik, W. J., & Kean, E. L. (2011). Sociosexuality moderates the association between testosterone and relationship status in men and women. Hormones and Behavior, 60, 248-255.

Engeler, I., & Raghubir, P. (2017). Decomposing the Cross-Sex Misprediction Bias of Dating Behaviors: Do Men Overestimate or Women Underreport Their Sexual Intentions? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Jul 13 , 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000105

Fenton, K. A., Johnson, A. M., McManus, S., & Erens, B. (2001). Measuring sexual behaviour: Methodological challenges in survey research. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 77, 84–92.

Fisher, T. D., & Brunell, A. B. (2014). A bogus pipeline approach to studying gender differences in cheating behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 61, 91-96.

Haeffel, G. J., & Howard, G. S. (2010). Self-report: Psychology's four-letter word. The American Journal of Psychology, 123, 181-188.

Harrell, A. V. (1985). Validation of self-report: The research record. In Self-Report Methods of Estimating Drug Use: Meeting Current Challenges to Validity. National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Monograph (Vol. 57, pp. 12-21).

Hamilton, D. T., & Morris, M. (2010). Consistency of self-reported sexual behavior in surveys. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 842-860.

Howell, J. L., Egan, P. M., Giuliano, T. A., & Ackley, B. D. (2011). The reverse double standard in perceptions of student-teacher sexual relationships: The role of gender, initiation, and power. The Journal of Social Psychology, 151, 180-200.

Langhaug, L. F., Sherr, L., & Cowan, F. M. (2010). How to improve the validity of sexual behaviour reporting: systematic review of questionnaire delivery modes in developing countries. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 15, 362-381.

Lippa, R. A. (2009). Sex differences in sex drive, sociosexuality, and height across 53 nations: Testing evolutionary and social structural theories. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 631-651.

McCallum, E. B., & Peterson, Z. D. (2012). Investigating the impact of inquiry mode on self-reported sexual behavior: Theoretical considerations and review of the literature. Journal of Sex Research, 49, 212-226.

Marks, M. J., & Fraley, R. C. (2005). The sexual double standard: Fact or fiction? Sex Roles, 52, 175-186.

McGahuey, Alan J. Gelenberg, Cindi A. Laukes, Francisco A. Moreno, Pedro L. Delgado, Kathy M. McKnight, Rachel Manber, C. (2000). The Arizona sexual experience scale (ASEX): reliability and validity. Journal of Sex &Marital Therapy, 26, 25-40.

Milhausen, R. R., & Herold, E. S. (1999). Does the sexual double standard still exist? Perceptions of university women. Journal of Sex Research, 36, 361-368.

Minnis, A. M., Steiner, M. J., Gallo, M. F., Warner, L., Hobbs, M. M., Van Der Straten, A., ... & Padian, N. S. (2009). Biomarker validation of reports of recent sexual activity: results of a randomized controlled study in Zimbabwe. American Journal of Epidemiology, 170, 918-924.

Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological Review, 84, 231-263.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Papp, L. J., Hagerman, C., Gnoleba, M. A., Erchull, M. J., Liss, M., Miles-McLean, H., & Robertson, C. M. (2015). Exploring perceptions of slut-shaming on Facebook: Evidence for a reverse sexual double standard. Gender Issues, 32, 57-76.

Paulhus, D.L., Lysy, D.C., & Yik, M.S. (1998). Self-report measures of intelligence: Are they useful as proxy IQ tests? Journal of Personality, 66, 525-554.

Paulhus, D. L., & Reid, D. B. (1991). Enhancement and denial in socially desirable responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 307-317.

Penke, L., & Asendorpf, J. B. (2008). Beyond global sociosexual orientations: a more differentiated look at sociosexuality and its effects on courtship and romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1113-1135.

Robertson, R. E., Tran, F. W., Lewark, L. N., & Epstein, R. (2017). Estimates of Non-Heterosexual Prevalence: The Roles of Anonymity and Privacy in Survey Methodology. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 1-16.

Scandell, D. J., Klinkenberg, W. D., Hawkes, M. C., & Spriggs, L. S. (2003). The assessment of high-risk sexual behavior and self-presentation concerns. Research on Social Work Practice, 13, 119-141.

Schmitt, D.P. (2005). Sociosexuality from Argentina to Zimbabwe: A 48-nation study of sex, culture, and strategies of human mating. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28, 247-275.

Schmitt, D.P. (2015). The evolution of culturally-variable sex differences: Men and women are not always different, but when they are…it appears not to result from patriarchy or sex role socialization. In Weekes-Shackelford, V.A., & Shackelford, T.K. (Eds.), The evolution of sexuality (pp. 221-256). New York: Springer.

Simpson, J. A. (1998) Sociosexual Orientation Inventory. In: Handbook of sexuality-related measures, ed. C. M. Davis, W. L. Yarber, R. Bauserman, G. Schreer & S. L. Davis, pp. 565–67. Sage.

Koss, M. P., & Gidycz, C. A. (1985). Sexual experiences survey: reliability and validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53, 422-423.

Simpson, J. A. & Gangestad, S. W. (1989) Two month test-retest reliability of the Sociosexual Orientation Inventory. Unpublished data, Texas A&M University.

Simpson, J. A. & Gangestad, S. W. (1991) Individual differences in sociosexuality: Evidence for convergent and discriminant validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 870–83.

Simpson, J. A. & Gangestad, S. W. (1992) Sociosexuality and romantic partner choice. Journal of Personality, 60, 31– 51.

Simpson, J. A., Gangestad, S. W., Christensen, P. N. & Leck, K. (1999) Fluctuating asymmetry, sociosexuality, and intrasexual competitive tactics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 76,159–72.

Simpson, J. A. & Orina, M. (2003) Strategic pluralism and context-specific mate preferences in humans. In: From mating to mentality: Evaluating evolutionary psychology, ed. K. Sterelny & J. Fitness, pp. 39–70. Psychology Press.

Simpson, J. A., Wilson, C. L. & Winterheld, H.A. (2004). Sociosexuality and romantic relationships. In: The handbook of sexuality in close relationships, ed. J. H. Harvey, A. Wenzel & S. Sprecher. pp. 87–112. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Smith, T. W. (1998). American sexual behavior: Trends, socio-demographic differences, and risk behavior. National Opinion Research Center.

Treas, J., & Giesen, D. (2000). Sexual infidelity among married and cohabiting Americans. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62, 48-60.

Tu, S. H., & Hsieh, S. H. (2017). Estimates of lifetime extradyadic sex using a hybrid of randomized response technique and crosswise design. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 373-384.

Graham, C. A., Catania, J. A., Brand, R., Duong, T., & Canchola, J. A. (2003). Recalling sexual behavior: a methodological analysis of memory recall bias via interview using the diary as the gold standard. Journal of Sex Research, 40, 325-332.

Turner, C. F., Miller, H. G., & Rogers, S. M. (1997). Survey measurement of sexual behavior. Researching sexual behavior: Methodological issues, 5, 37-60.

Weinhardt, L. S., Forsyth, A. D., Carey, M. P., Jaworski, B. C., & Durant, L. E. (1998). Reliability and validity of self-report measures of HIV-related sexual behavior: progress since 1990 and recommendations for research and practice. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 27, 155-180.

Wiederman, M. W. (1993). Demographic and sexual characteristics of nonresponders to sexual experience items in a national survey. Journal of Sex Research, 30, 27-35.

Shrout et al. (2017). Initial elevation bias in subjective reports. PNAS. Published online before print December 18, 2017, doi:10.1073/pnas.1712277115 PNAS December 18, 2017.

Wiederman, M. W. (1997). The truth must be in here somewhere: Examining the gender discrepancy in self‐reported lifetime number of sex partners. Journal of Sex Research, 34, 375-386.

Zimmerman, R. S., & Langer, L. M. (1995). Improving estimates of prevalence rates of sensitive behaviors: The randomized lists technique and consideration of self‐reported honesty. Journal of Sex Research, 32, 107-117.

Ó Ciardha, C., Attard-Johnson, J., & Bindemann, M. (2017). Latency-based and Psychophysiological Measures of Sexual Interest Show Convergent and Concurrent Validity. Archives of Sexual Behavior.

Mitchell, K.R., Catherine H. Mercer, Philip Prah, Soazig Clifton, Clare

Tanton, Kaye Wellings & Andrew Copas (2018): Why Do Men Report More Opposite-Sex Sexual

Partners Than Women? Analysis of the Gender Discrepancy in a British National Probability

Survey, The Journal of Sex Research, DOI: 10.1080/00224499.2018.1481193

Brewer, D. D., Potterat, J. J., Garrett, S. B., Muth, S. Q., Roberts, J. M., Kasprzyk, D., ... & Darrow, W. W. (2000). Prostitution and the sex discrepancy in reported number of sexual partners. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97(22), 12385-12388.

King. B.M. et al. (2019). Social Desirability and Young Men’s Self-Reports of Penis Size. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0092623X.2018.1533905?

Gerlach, T. M., Arslan, R. C., Schultze, T., Reinhard, S. K., & Penke, L. (2019). Predictive validity and adjustment of ideal partner preferences across the transition into romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 116, 313-324.