Sex

Sex Differences in Romantic Jealousy: Evolved or Illusory?

Gender...how does it make your brown eyes green?

Posted May 11, 2016

In everyday conversation, people often use the words "envy" and "jealousy" interchangeably. Scientists, however, tend to distinguish between these two emotions. Feeling envy is about desiring the possessions or qualities of someone else (e.g., I want her wealth, I wish I had his way with words). I definitely envy Stephen Curry's jump shot.

Jealousy is different, it’s about wanting to prevent the loss of something you already have (e.g., I don't want to lose my authority over others, I wish my current romantic partner would not stray). Envy and jealousy are related emotions, for sure, but each is psychologically specific in its own way.

The feeling of romantic jealousy is something even more specific. Nearly everyone has felt it, and its effects can be devastating. Heck, it's launched a thousand ships!

Although romantic jealousy has been studied for over 100 years, it wasn't until theorizing by 1990s evolutionary psychologists that sexual scientists began to consider how men and women might experience jealousy a little bit differently, given our differing reproductive biologies.

In 1992, Buss and his colleagues used evolutionary principles to hypothesize men might get more upset at the sexual infidelity of their romantic partners (because men, but not women, face the adaptive problem of paternity uncertainty and the fitness-damaging possibility of cuckoldry—spending huge amounts of parental effort on an unrelated child, often the child of a reproductive rival). Women, in contrast, might get more upset at the emotional infidelity of their romantic partners (because women incur greater costs than men when their partner defects and devotes all status and resources to a new, often younger family).

As noted by Buss and Haselton (2005), one of the most impressive aspects of the 1990s “sex differences in jealousy hypothesis” made by evolutionary psychologists was that not a single psychologist had ever made that prediction before. Not one, ever. It took an evolutionary perspective to guide psychologists to predict men and women might get upset differently, based in part on their differing reproductive interests.

Since the early 1990s, over 100 studies have investigated whether, and to what degree, sex differences exist in the psychology of sexual versus emotional jealousy. This post contains a Top 10 List of especially informative findings regarding the sex differences in jealousy hypothesis (for most references, see Buss, D. M., & Haselton, M. (2005). The evolution of jealousy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9, 506-507; and Buss, D. M. (2013). Sexual jealousy. Psychological Topics, 22, 155-182):

1) Sex differences in sexual versus emotional jealousy are meta-analytically robust (especially when analyzed appropriately, Sagarin et al., 2012; Tagler & Jeffers, 2013).

Many factors—other than Darwinian selection pressures—influence reactions to romantic betrayal (Buss, 2013). Consequently, evolutionary psychologists do not expect all (or even most) men will always find sexual infidelity more upsetting, whereas all or most women will always find emotional infidelity more upsetting. Factors particularly affecting sex differences in jealousy responses across studies include the precise ways “infidelity” is defined, anchoring effects from the wording used on response scales, the tendency for women to generally report more intense emotions than men, and the fact that cultures vary in overall rates of infidelity.

All these factors and more might shift men’s and women’s upset responses more toward sexual or emotional infidelity in any given research study. Given these considerations, it has been argued the most appropriate way to evaluate the sex differences in jealousy hypothesis is to test for a Participant Sex × Infidelity Type statistical interaction within a given study (Sagarin et al., 2012; see also Buss & Haselton, 2005, who advocate for examining 2 separate tests: 1) sex differences in sexual fidelity reactions, and 2) sex differences in emotional fidelity reactions; when combined these effects should typically result in a Participant Sex × Infidelity Type interaction effect).

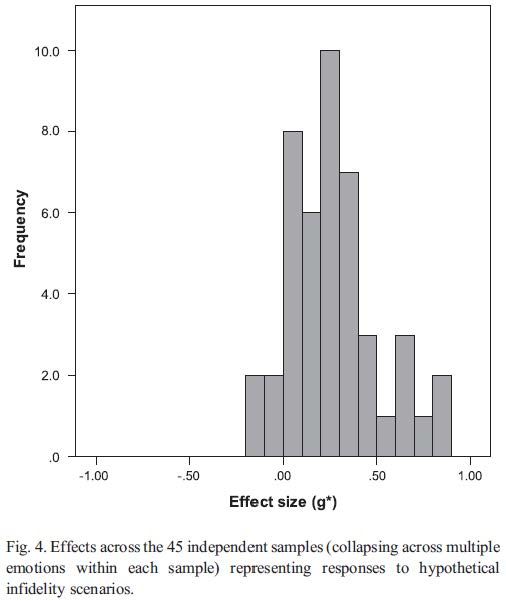

Using these appropriate statistical testing approaches, in a meta-analysis of 72 studies (Hofhansl, Voracek, & Vitouch, 2004), the overall meta-analytic sex difference in jealousy psychology was moderate to large in size (d = 0.64). Across different types of scales, sometimes the effect size is smaller. Sagarin et al. (2012) found a small sex difference d = .26 across 45 samples that only used continuous scales (forced choice scales tend to produce larger effects; see also Edlund, 2008). Even with continuous scales, though, strong effects are observed if the upper end of continuum is spread out (Sagarin, 2004).

So, overall, sex differences in jealousy should probably be considered meta-analytically robust. Larger effects are evident when using forced choice measures, and when the effect is properly tested as a Participant Sex × Infidelity Type statistical interaction.

2) Sex differences in sexual versus emotional jealousy (i.e., Participant Sex × Infidelity Type statistical interactions) are robust across cultures, including samples from the United States, Canada, England, Ireland, Norway, Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Romania, Brazil, Chile, Australia, China, Japan, Korea, and the Himba of Namibia (see Buss, 2013; Buss & Haselton, 2005).

3) Sex differences in sexual versus emotional jealousy are robust using objective physiological measures (e.g., sex differences are found in heart rate, blood pressure, corrugator brow contraction, skin conductance, and other physical responses when men and women imagine different types of infidelity; see Buss, 2013). Recently, physiological-related jealousy sex differences were observed in affective modulation of startle eyeblink responses (importantly, this research employed several statistical controls; Baschnagel & Edlund, 2016). These studies further confirm sex differences are not simply an artifact of self-report methods.

4) Sex differences in sexual versus emotional jealousy are robust when evaluating jealousy-related cognitive measures, such as involuntary attention, information search, decision time, and memory for cues to sexual versus emotional infidelity (Buss, 2013). For instance, Schutzwohl (2010) found men show greater recall of cues to sexual infidelity, women show greater recall of cues to emotional infidelity. Maner (2009) found the implicit cognitions of men and women follow predicted patterns.

5) fMRI studies reveal different patterns of jealousy-related brain activation across the sexes, supporting hypothesized sex differences in jealousy (Takahashi et al., 2006).

6) Sex differences in sexual versus emotional jealousy are robust across demographic factors such as age, income levels, history of being cheated on, history of being unfaithful, relationship type, length. Factors such as age, income, and whether participants have had children are all unrelated to sex differences in upset over sexual/emotional infidelity (Frederick, 2015; Zengel et al., 2013).

7) Sex differences in sexual versus emotional jealousy are not due to the double-shot hypothesis (emotional infidelity may imply sexual infidelity when women think about men, DeSteno & Salovey, 1996). When emotional and sexual implications are explicitly de-linked, sex differences are still apparent (Buss et al., 1999; Cramer, 2001).

8) Sex differences in sexual versus emotional jealousy show predictable patterns of automaticity. DeSteno et al. (2002) a frequent (and frequently proven wrong) critic of evolved sex differences in jealousy purportedly found no sex differences in jealousy automaticity. Schutzwohl (2008) noted DeSteno et al. (2002) did not counter balance jealousy choices in his experimental design, and when counter balanced correctly (which Schutzwohl did in a 2008 study), sex differences in jealousy do show automaticity. Questionable research practices, indeed.

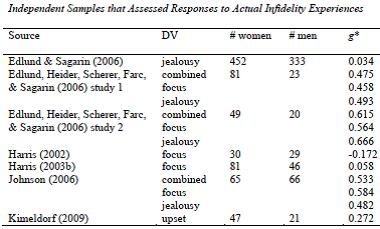

9) Sex differences in sexual versus emotional jealousy emerge (often stronger) in cases of real life infidelity. Sex differences in jealousy emerge when looking at retrospective reports of actual infidelity experience (Edlund, 2006). Kuhle (2011) found men ask more about “did you sleep with him?” whereas women more “do you love her?” in Cheaters television program (alright, perhaps not exactly “real” life, but not just self-reported survey responses, either).

Sagarin (2003) also found sex differences were greater among men who have actually experienced a sexual betrayal, and among women who have sexually betrayed a man (see also, Burchell, 2011; cf. Frederick, 2015). Of the 13 studies on the topic of actual infidelity, reviewed in a meta-analysis (Sagarin et al., 2012), the unweighted average effect size of sex differences in jealousy was d = .39.

10) Sex differences in sexual versus emotional jealousy are not simply side effects or by products of other psychological sex differences, such as attachment styles (Levy, 2011; Tagler, 2011). Brase and his colleagues (2014) recently examined many potential proximate mediators (infidelity implications beliefs, gender-role beliefs, interpersonal trust, attachment style, sociosexuality, and culture of honor beliefs) and found a consistent sex difference that was not mediated by any other variables.

But even if there were some mediators, it wouldn't mean the sex difference is not in any way “evolved.” Instead, it might mean sex differences in sociosexuality or attachment might be part of the causal developmental pathway of an evolved jealousy sex difference (as would finding the sex difference is related to testosterone, height, or any other developmentally reliable evolved sex difference; see Buss & Schmitt, 2011; Schmitt, 2015). Indeed, evolution often appears to count on reliable sex differences in one domain (e.g., dismissing attachment) to play a role in manifesting adaptive sex differences in another domain (e.g., sociosexuality; Schmitt, 2005). Again, though, Brase et al. did not find any mediation of evolved sex differences in jealousy, so we have to look elsewhere for the causal mechanisms that seem to reliably give rise to jealousy-related sex differences.

A Few Caveats

Many contextual factors influence the degree to which jealousy is experienced by men and women (including compersion), but most empirically-verified contextual factors actually support evolutionary hypotheses about sex differences in jealousy. For instance, jealousy is experienced more by low mate value men (Phillips, 2010), shorter men (Buunk, 2008), shorter-than-partner men (Brewer, 2010), when a male mate poacher is of high status (Buss, 2000), and when a female mate poacher is highly attractive (Buss, 2000). Jealousy, it appears, is calibrated by many evolutionary considerations (especially self and rival attributes, Buss, 2013).

There also is evidence that in some cultures heightened concern over paternity certainty may evoke in men extremely high concerns over sexual fidelity. Among a small-scale, natural fertility population, the Himba of Namibia, 31% of women admit to having at least one child from an extra-marital affair (Scelza, 2011). This is a very high cuckoldry rate (most studies find only about 2% of children are the concealed result of an extra-marital affair; Anderson, 2006). It appears extremely high rates of infidelity facultatively evoke even greater concern among men over the sexual fidelity of their partners, with 96% of Himba men finding sexual infidelity more upsetting than emotional infidelity (Scelza, 2014).

Women also feel especially upset at sexual infidelity among the Himba, but the sex difference is still evident, “the standard sex difference persists in these data, and is highly significant with men much more likely to be upset by the sexual infidelity than women (χ2 = 13.89, df = 1, p < 0.001)” (Scelza, 2014, p. 105). Indeed, although Himba women choose sexual infidelity as more upsetting more 66% of the time (more than women in WEIRD cultures, about 20%), the effect size of the sex difference among the Himba, d = .80, is actually much larger than the overall effect size in meta-analyses of WEIRD samples, d = .24 (Sagarin et al., 2012).

Of course, even if the sex difference were not apparent in a particular culture, this would not indicate that the sex differences seen in most cultures are not in any way evolved. Most sex differences are sensitive to ecological and sociocultural contexts, sometimes by design (via facultative adaptations) and sometimes as an inadvertent side effect of other factors, including other adaptations (through facultative mediation or emergent moderation; see Schmitt, 2015).

For example, religions sometimes accentuate--and probably more often suppress--evolved sex differences, such as the Shaker religion not allowing any sexual contact between men and women, so no sex differences in reproductive strategies there! Another example is the sex difference in height. Among cultures in high altitude ecologies, the sex difference in height is minimized and sometimes nearly absent as shorter body frames provide for much better survival (Gaulin, 1992; Gaulin & Sailer, 1983). Across most ecologies, though, sex differences in height are readily seen, and even manifest as the largest in nations that have the most sociopolitical gender equality (such as in Scandinavian nations; for fuller discussion of these issues, see Schmitt, 2015).

In Sum

Sex differences in sexual versus emotional jealousy are robust meta-analytically, across cultures, using objective measures of physiological distress, using cognitive-related measures, in brain activation differences, and across demographic factors such as age, income levels, history of being cheated on, history of being unfaithful, relationship type, and relationship length.

Sex differences in sexual versus emotional jealousy are not due to the double-shot hypothesis, nor are they simply side effects of other psychological sex differences such as attachment styles. Sex differences in sexual versus emotional jealousy show predictable patterns of automaticity, and emerge (often more strongly) in cases of real life infidelity.

Time will tell whether all of these effects continue to replicate (and whether the evolutionary explanations of these effects are confirmed using converging lines of evidence, as with sex differences in mate preferences). At this point, what is clear is that critics of the “sex differences in jealousy hypothesis” should take heed of these many supportive findings, and fully account for them with compelling alternative theories, before claiming sexual diversity scientists should entirely dismiss such important and consequential sex differences in psychological design.

Key References

Brase, G. L., Adair, L., & Monk, K. (2014). Explaining sex differences in reactions to relationship infidelities: Comparisons of the roles of sex, gender, beliefs, attachment, and sociosexual orientation. Evolutionary Psychology, 12, 73-96.

Buss, D. M. (2013). Sexual jealousy. Psychological Topics, 22, 155-182):

Buss, D. M., & Haselton, M. (2005). The evolution of jealousy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9, 506-507.

Buss, D. M., Larsen, R. J., Westen, D., and Semmelroth, J. (1992). Sex differences in jealousy: Evolution, physiology, and psychology. Psychological Science, 3, 251-255.

Schmitt, D.P. (2015). The evolution of culturally-variable sex differences: Men and women are not always different, but when they are…it appears not to result from patriarchy or sex role socialization. In Weekes-Shackelford, V.A., & Shackelford, T.K. (Eds.), The evolution of sexuality (pp. 221-256). New York: Springer.