Sex

Sex Differences in Talkativeness?

Women don’t talk more than men do; well, a little more

Posted March 17, 2016

Women sure do talk a lot more than men, right? Well, not so fast. There are quite few ways to evaluate whether women talk more than men (or vice versa). Should we define talking as total words spoken in a day, total turns taken in a conversation, the speed of talking, the time duration of a typical talking episode, or what?

Depending on how you look at it, most studies find sex differences in talkativeness range from the very small to the merely moderate (expressed in d values, small sex differences are about +/- 0.20, moderate differences +/- 0.50, large differences +/- 0.80; with negative values indicating women are more talkative, positive values indicating men are more talkative).

Let’s take a look at some of the evidence.

Stereotypes about Talkativeness in Women and Men

Tannen (1990) was a prominent proponent of the idea women talk differently than men, especially that women talk about different things, and in different ways, than men do (see also, Haas, 1979). Talkativeness as a trait is traditionally considered more feminine than masculine (Crawford, 1995; Helgeson, 2015), especially among men (e.g., it is perceived as stereotypical of gay men; Madon, 1997). Still, although many stereotypes are accurate to some degree (Jussim et al., 2015), it may be in this case that women’s greater level of talkativeness just isn’t so.

Self-Reports of Talkativeness in Women and Men

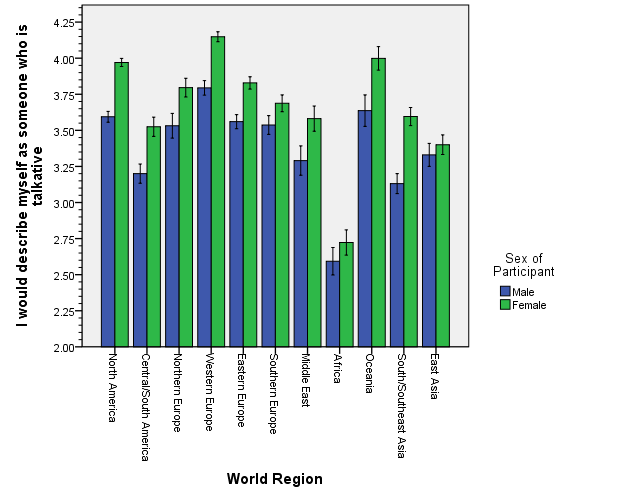

Most studies of self-reported talkativeness (part of the Big Five trait of Extraversion) find women report being a little more talkative than men. In the ISDP-2 (a study of 58 nations across 11 world regions; Schmitt et al., 2016), women agreed more than men did with the statement “I would describe myself as someone who is talkative” across most world regions (less so in Africa and East Asia), with an average effect size of d = -0.27.

These sex differences in talkativeness, though small, match the degree to which men and women differ in saying they enjoy talking (e.g., agreeing with statements like "I really enjoy having long conversations" or "The days that I enjoy the most are days when I have been able to talk a lot" Kennison, Byrd-Craven, & Hamilton, 2017). And most importantly, self-reports of one's talkativeness generally do predict actual talkativeness during a typical day (at least in the USA; Mehl et al., 2008).

Indirect Aggression (Gossip) of Women and Men

There is some evidence women are more verbally aggressive than men, particularly in their use of indirect aggression via tactics such as gossip (Hess & Hagen, 2006; McAndrew et al., 2007). For instance, women spend more time gossiping than men and are much more likely than men to gossip about close friends and family members (Levin & Arluke, 1985). Among friends, women tend to gossip more about physical appearance, whereas men gossip more about achievement (Watson, 2012). Gossiping, though, is a rather small part of the experience of talking within most people’s lives.

Couple Complaints about Talkativeness by Women and Men

When heterosexual partners complain about each other, some sex differences emerge related to talkativeness (Buss, 1989; Gottman et al., 1998). For instance, women’s satisfaction is more dependent on whether their mate withdraws from verbal interaction (Heavey et al., 1995). These effects are slight, much like sex differences in stereotypes and self-reports of talkativeness. Still, if men and women perfectly assort on the trait of talkativeness, even a very small sex difference would mean women are always the more talkative partner within heterosexual couples. Assortative mating could be part of the reason women are perceived (even by themselves) as talking more than men.

Neurology of Talkativeness in Women and Men

There are some indications that sex differences in talkativeness and verbal abilities stem from neurological differences between men and women (Baxter et al., 2003; Knickmeyer & Baron-Cohen, 2006; Weiss et al., 2003). For instance, the FOXP2 gene is central to acquisition of speech and language in humans (and many other animals), with mutations in the FOXP2 gene producing severe language and speech impairments in humans (Bowers & Konopka, 2012). In a study of children aged four to five years who had died in accidents less than 24 hours previously, researchers found 30% more FOXP2 protein in the brains of girls compared to boys (Bowers et al., 2013).

Development of Talking Abilities in Women and Men

Several lines of evidence suggest women have better verbal abilities in some domains, men in other domains. For instance, women tend to be better at spelling, language ability, grammatical usage, and verbal memory (Kimura, 1999). Of course, even if women have advantages over men at certain abilities related to talking, that doesn’t mean they talk more.

Actual Talking Behavior in Women and Men

Mehl et al. (2007) examined sex differences in talkativeness the old-fashioned way…they measured naturalistic talking in everyday life (by using a recording device that captured actual talking). Their recording device, called an electronically activated recorder (EAR for short) records 30 seconds every 12.5 minutes. This EAR device allowed Mehl et al. to capture 5% of every women’s and men’s day to look for differences in talking. Their overall results suggested women talk only a little more than men. Across 6 samples, they found women spoke 16,215 words per day, whereas men spoke about 15,669 words per day (a very small difference, d = -0.07).

However, one of their study samples was rather peculiar, both in terms of the size of the sex difference (men spoke over 8,000 more words than women per day), the size of the sample (it included only 7 women and 4 men), and the sampling time period (it recorded spoken words from September 11th, 2001 through September 20th, 2001). Including this sample seems rather inappropriate, as it represents talkativeness after the United States homeland had just been massively attacked by terrorists (this means war!). Excluding this peculiar sample results in an observed sex difference that is more in line with previous studies (women talked more than men, d = -0.13).

More recently, Manson (2018) used the EAR device to examine whether sex differences in talking might reflect sex differences in life history strategy. Again, women tended to talk just a little bit more than men (d = -0.34), though this effect was only statistically significant when accounting for life history strategy. That is, people with slow life histories tend to talk less (and to use fewer swear words, sexual words, and affect words [particularly negative emotion and anger words]). It was only after controlling for life history strategy that women were significantly more talkative than men.

Onnela et al. (2014) examined talking among 79 students while they worked on a collaborative task for twelve hours. Women were much more talkative than men, especially when physically close and in small groups (e.g., when close to one other person, women talked over twice as much as when men were close to one other person).

Across multiple types of settings (e.g., laboratories, schools), Leaper and Smith (2004) conducted a meta-analysis of sex differences in talkativeness among children. On average, girls were slightly more talkative than boys (d = -0.11). In a follow-up meta-analysis of sex differences in talkativeness among mothers’ and fathers’ speech to their children, Leaper, Anderson, and Sanders (1998) again found mothers talked more with their children than fathers (d = -0.26).

In a meta-analysis of sex differences among adults (Leaper & Ayres, 2007), women were much more talkative in studies of classmates (d = -0.54) and again in studies of parents with their children (d = -0.42), and women were a tiny bit more talkative among friends (d = -0.06). Men were more talkative when with spouses or partners (d = 0.38), mixed-familiarity groups (d = 0.23), and strangers (d = 0.17). These latter findings are consistent with other qualitative reviews finding men talk more when in mixed-sex groups (James & Drakich, 1993).

So, who is more talkative behaviorally…it depends. If there is an overall sex difference with women more talkative than men, it is relatively small and it is heavily dependent on context.

Social Media Communication

Tannen (1990) argued who talks more, women or men, depends on whether one examines talking in private or public. Stereotypically, women talk more in the privacy of home, but less at public meetings. As Kendall and Tannen (2001) noted, in an analysis of social media communication, Herring and Stoerger (2014) reviewed extant research and found women outnumber and are more socially active than men on social networking sites such as Facebook, the microblogging site Twitter, the consumer review site Yelp, and the online pinboard Pinterest, whereas men participate more on music-sharing sites, the professional social networking site LinkedIn, and the social news website, Reddit.

In 2014, Joiner et al. examined public communication on social media, particularly Facebook (see also, Park et al., 2016). They found women were much more likely to ‘like’ a Facebook status update than men are, and women are also more likely to post a public reply to a Facebook status update and show higher levels of emotional support than men do. Privately, though, women were only a little more likely to message than men. Also important are distinctions between whether social communication takes place within or across the sexes (Joiner et al., 2016).

Caveats

Overall, sex differences in talkativeness seem pretty small (probably a best guess would be around d = -0.13), but sex differences in the content of what is talked about may important, too.

Women, for instance, tend to focus on affective aspects of communication, whereas men focus more on instrumental aspects of communication (Burleson et al., 1996). The Leaper and Smith (2004) meta-analysis on children’s talkativeness confirms this, finding girls were more likely to talk in terms of affiliation (d = -0.26), whereas boys were more likely to engage in assertive speech (d = 0.11). In the follow-up meta-analysis on sex differences in talkativeness among adults, women used more affiliative speech (d = -0.12), whereas men were found to use more assertive speech (d = 0.09). And, of course, there is the issue of what men and women talk about social media. Park et al. (2016) examined Facebook language use and found moderately-sized sex differences in the use of affiliative language (in use of words like family, friends, loving, and grateful; d = -0.51). Sex differences in assertive language were smaller (e.g., use of words like party, rockin, or poppin).

All in all, sex differences in talkativeness appear to be pretty small. But perhaps the content differences in what men and women talk about and how they talk (affiliatively versus assertively) causes people to perceive larger sex differences in talkativeness than actually exist. Of course, that’s just an assertion.

References

Baxter, L., Saykin, A., Flashman, L., Johnson, S., Guerin, S., Babcock, D., Wishart, H. (2003). Sex differences in semantic language processing: a functional MRI study. Brain Lang. 84, 264–272.

Bowers, J. M., Perez-Pouchoulen, M., Edwards, N. S., & McCarthy, M. M. (2013). Foxp2 mediates sex differences in ultrasonic vocalization by rat pups and directs order of maternal retrieval. The Journal of Neuroscience, 33, 3276-3283.

Bowers, J. M. & Konopka, G. (2012). The role of the FOXP family of transcription factors in ASD. Disease Markers, 33, 251–60.

Burleson, B. R., Kunkel, A. W., Samter, W., & Working, K. J. (1996). Men's and women's evaluations of communication skills in personal relationships: When sex differences make a difference and when they don't. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 13, 201-224.

Buss, D. M. (1989). Conflict between the sexes: strategic interference and the evocation of anger and upset. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 735-737.

Crawford, M. (1995). Talking difference: On gender and language (Vol. 7). Sage.

Gottman, J. M., Coan, J., Carrere, S., & Swanson, C. (1998). Predicting marital happiness and stability from newlywed interactions. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 5-22.

Haas, A. (1979). Male and female spoken language differences: Stereotypes and evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 86, 616.

Hall, J. A. (1984). Nonverbal sex differences: Communication accuracy and expressive style. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Heavey, C. L., Christensen, A., & Malamuth, N. M. (1995). The longitudinal impact of demand and withdrawal during marital conflict. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 63, 797.

Helgeson, V. (2015). Psychology of gender. Psychology Press.

Herring, S.C. & Stoerger, S. (2014). Gender and (a)nonymity in computer-mediated communication. In Susan Ehrlich, Miriam Meyerhoff, and Janet Holmes, eds., The Handbook of Language, Gender, and Sexuality, 2nd edn. Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 567–86.

Hess, N. H., & Hagen, E. H. (2006). Sex differences in indirect aggression: Psychological evidence from young adults. Evolution and Human Behavior, 27, 231-245.

Hyde, J. S., & Linn, M. C. (1988). Gender differences in verbal ability: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 104, 53-69.

James, D., & Drakich, J. (1993). Understanding gender differences in amount of talk: A critical review of the research. In D. Tannen (Ed.), Gender and conversational interaction (pp. 281-312). New York: Oxford University Press.

Joiner, R., Cuprinskaite, J., Dapkeviciute, L., Johnson, H., Gavin, J., & Brosnan, M. (2016). Gender differences in response to Facebook status updates from same and opposite gender friends. Computers in Human Behavior, 58, 407-412.

Joiner, R., Stewart, C., Beaney, C., Moon, A., Maras, P., Guiller, J., ... & Brosnan, M. (2014). Publically different, privately the same: Gender differences and similarities in response to Facebook status updates. Computers in Human Behavior, 39, 165-169.

Jussim, L., Crawford, J. T., & Rubinstein, R. S. (2015). Stereotype (In)Accuracy in Perceptions of Groups and Individuals. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24, 490-497.

Kendall, S., & Tannen, D. (2001). Discourse and gender. The Handbook of Discourse Analysis, 2, 639-660.

Kennison, S. M., Byrd-Craven, J., & Hamilton, S. L. (2017). Individual differences in talking enjoyment: The roles of life history strategy and mate value. Cogent Psychology, 4, 1395310.

Kimura, D. (1999). Sex differences, brain organization for speech and language, In: Adelman, G., Smith, B. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Neuroscience, 2nd ed. Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, pp. 1849–1851.

Knickmeyer, R. C., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2006). Topical review: Fetal testosterone and sex differences in typical social development and in autism. Journal of Child Neurology, 21, 825-845.

Leaper, C., & Ayres, M. M. (2007). A meta-analytic review of gender variations in adults' language use: Talkativeness, affiliative speech, and assertive speech. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11, 328-363.

Leaper, C., & Smith, T. E. (2004). A meta-analytic review of gender variations in children's language use: talkativeness, affiliative speech, and assertive speech. Developmental Psychology, 40, 993-1027.

Levin, J., & Arluke, A. (1985). An exploratory analysis of sex differences in gossip. Sex Roles, 12, 281-286.

Madon, S. (1997). What do people believe about gay males? A study of stereotype content and strength. Sex Roles, 37, 663-685.

Manson, J. H. (2018). Life history strategy and everyday word use. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 4, 111-123.

McAndrew, F. T., Bell, E. K., & Garcia, C. M. (2007). Who Do We Tell and Whom Do We Tell On? Gossip as a Strategy for Status Enhancement. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 37, 1562-1577.

Mehl, M. R., Gosling, S. D., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2006). Personality in its natural habitat: Manifestations and implicit folk theories of personality in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 862-877.

Mehl, M. R., Vazire, S., Ramírez-Esparza, N., Slatcher, R. B., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2007). Are women really more talkative than men? Science, 317, 82-82.

Onnela, J. P., Waber, B. N., Pentland, A., Schnorf, S., & Lazer, D. (2014). Using sociometers to quantify social interaction patterns. Scientific Reports, 4.

Park G, Yaden DB, Schwartz HA, Kern ML, Eichstaedt JC, Kosinski M, et al. (2016) Women are Warmer but No Less Assertive than Men: Gender and Language on Facebook. PLoS ONE 11(5): e0155885. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0155885

Tannen, D. (1990). You just don’t understand: Women and men in conversation. New York: Morrow.

Watson, D. C. (2012). Gender differences in gossip and friendship. Sex Roles, 67, 494-502.

Weiss, E., Siedentopf, C., Hofer, A., Deisenhammer, E., Hoptman, M., Kremser, C., Golaszewski, S., Felber, S., Fleischhacker, W., Delazer, M. (2003). Brain activation pattern during a verbal fluency test in healthy male and female volunteers: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuroscience Letters, 352, 191–194.