Testosterone

Sex, Gender, and Testosterone

Is being masculine just hormonal, or is it chromosomal too?

Posted February 5, 2016

Hormones can matter a lot when explaining sexual diversity in humans. However, just because hormones might be linked to some feature of sexuality doesn’t mean the hormones caused it. In many cases, hormones change as a result of sexual behaviors, rather than sexual behaviors being the consequence of hormone variations (Goldey & van Anders, 2014; Muller et al., 2009).

Some sexual diversity scholars have suggested many of the hormonal differences between men and women (and most of the psychological sex differences that seem connected to hormonal differences) largely result from men and women undergoing differential socialization experiences and inhabiting different social roles (e.g., Wood & Eagly, 2012). If men and women were raised exactly the same, and held identical positions and roles across society, for instance, it is expected there would be little to no sex differences in hormones such as testosterone (Butler, 2002).

In a recent paper, van Anders and her colleagues (2015) tried to experimentally test certain facets of this view. They measured testosterone levels in 26 men and 15 women who were trained actors. They asked the actors to portray a “boss” in different workplace scenes on different days. Participants were asked either to play a boss who fires someone in a “stereotypically masculine way” such as taking up space, using dominance posturing, and displaying infrequent smiles or in a “stereotypically feminine way” such as upending sentences, hesitating, and displaying infrequent eye contact. All participants also were asked to engage in a presumably hormone-neutral control activity (i.e., watching a travel documentary).

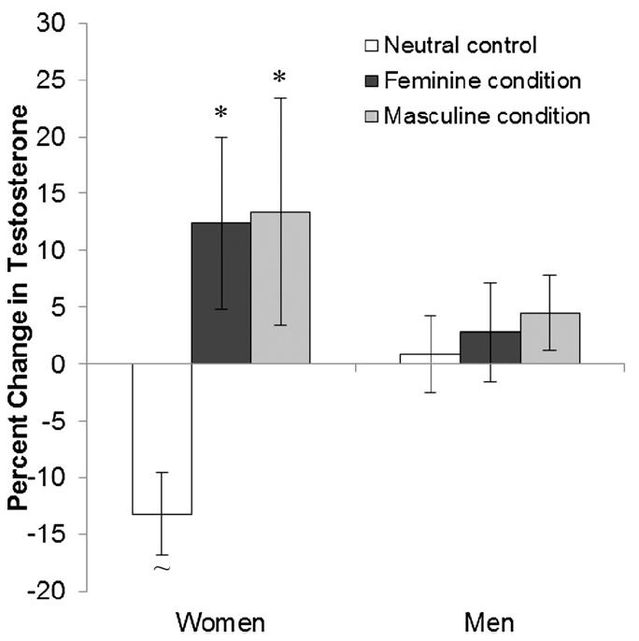

What happened to their hormone levels on these different days? For the men, not a lot. Relative to the hormone-neutral control condition, playing a role in which they were a boss firing people raised men’s testosterone about 3% or so, and it didn’t matter whether they did so in a masculine or feminine way. The average 29 year old man (the average participant age) has a total testosterone level of about 600ng/dL (nanograms per deciliter), so this would represent a jump to about 618ng/dl (this is just an estimation, actual jumps in mean testosterone levels were unreported in the paper). The testosterone jumps in men due to acting like a boss were statistically insignificant, though, and very small in terms of effect size. Not a whole lot there.

For women, it was a different story. Relative to the hormone-neutral control condition, playing a role in which they were a boss firing people raised women’s testosterone about 13% or so, and again it didn’t matter whether they did so in a masculine or feminine way. The average 29 year old woman (the average participant age) has a total testosterone level of about 60ng/dL, so this is a jump to about 68ng/dl. These effects were statistically significant, and had (d) effect sizes in the .50 to .70 range—rather impressive effect sizes.

It is interesting that acting as a boss in a masculine manner did not increase testosterone more than acting as a boss in a feminine manner. van Anders and her colleagues (2015) interpreted this as suggesting that power (i.e., being a boss), but not being masculine in the performative way one is a boss, is what causes testosterone to jump up in women. This also would seem to disconfirm the notion that “masculinity” directly causes increases in testosterone, whereas “femininity” causally inhibits testosterone. Instead, it seems safe to conclude that just acting as a boss (or perhaps just acting at all, given there was no acting control condition) does the trick for increasing testosterone. Actors do have especially high testosterone (the highest testosterone of all professions, ministers have the lowest; Dabbs & Dabbs, 2000). Maybe years of acting really does raise testosterone over the long haul for actors (or maybe people with higher testosterone go into acting; or maybe both).

Unfortunately, some media reports have focused on an inappropriate inference from these findings, suggesting that men tending to inhabit masculine social roles and women tending to inhabit feminine roles is a key source of sex differences in testosterone. That is, some journalists are assuming that if women fired people as bosses just as much as men do (and men and women inhabited identical roles throughout society), there would be no sex differences in testosterone levels. While certainly possible (however biologically implausible), the data from this study do not support this inference. Sex differences in testosterone were not reduced in the acting condition, in fact the sex difference may have gotten bigger!

Look at the above numbers again. Yes, the testosterone-generating effects on actors of playing a boss appeared to be more prominent among women (specifically, as expressed as a “percentage change”), but the sex differences in testosterone were not eliminated in this special “power acting” situation. Not even close (estimated hormone levels in these conditions were 618ng/dL for men versus 68ng/dL for women). Indeed, because men have much higher levels of testosterone to begin with, although they have a smaller “percentage increase” when acting as a boss, the raw sex differences in testosterone were probably LARGER in the acting as a boss conditions (men = 618 versus women = 68; 618 – 68 means men were 550 higher than women), compared to men and women generally (men = 600 versus women = 60; 600 – 60 means men were 540 higher than women).

These numbers are just estimates (again, actual data on mean testosterone levels were left unreported in the original study, for some unknown reason the authors only reported the percentage changes). What is clear is that it is rather misleading to conclude from this study that sex differences in testosterone are increased by social roles such as being a boss (or being a masculine boss more than a feminine boss). Percentage changes are greater in women than men, yes; but the actual sex differences in testosterone likely get bigger when acting like a boss!

It is important to note there is a lot of natural variability in testosterone levels within men and women (e.g., According to the National Institutes of Health, the normal range of testosterone is 300 to 1,200ng/dL for men, and about 30 to 95ng/dL for women), and sometimes extremely high or low testosterone scores can affect results in studies like this. Demographic confounds such as age and being in a relationship also can affect men’s and women’s testosterone levels differently. van Anders and her colleagues (2015) controlled for these factors in additional analyses, and the above results held up well.

In sum, this study is a fascinating investigation into the effects of “acting like a boss” on testosterone levels. Acting like a masculine boss does not increase testosterone more than acting like a feminine boss, but just acting like a boss (and maybe just acting generally) does appear to increase testosterone (more so in women if looked at as a percentage change; likely less so in women if looked at as a raw mean-level change). Again, given men’s much higher levels of testosterone overall, the percentage changes reported by van Anders et al. (2015) signify that mean-level sex differences in testosterone probably grow LARGER when men and women act like a boss.

It also is important to note the change in testosterone among women (+8ng/dL) is miniscule compared to sex differences in testosterone generally (600 versus 60ng/dL = 540ng/dL). As a comparison, the jump in women’s testosterone (+8ng/dL) given the size of the typical sex difference in testosterone (540ng/dL) would be the equivalent of women’s average height increasing about 2 millimeters (with average sex difference in height being about 5½ inches; Stulp et al., 2013) in a special social role. Demonstrating that inhabiting a special social role could increase women’s average height by 2 millimeters (or any height) would be fascinating, for sure, but it would not imply the 5½ inch difference between men and women is entirely due to social roles. Mountains and mole hills come to mind.

One next step would be to see if acting in other ways (e.g., like a baby, like a minister, whatever) also raises women’s testosterone more than men’s (as a percentage) and increases the sex difference in testosterone (in terms of mean levels). And hopefully, future studies will report the mean testosterone levels across conditions in addition to the potentially misleading percentage changes. One can hope.

Butler, J. (2002). Gender trouble. New York: Routledge.

Dabbs, J. M., & Dabbs, M. G. (2000). Heroes, rogues, and lovers: Testosterone and behavior. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Goldey, K. L., & van Anders, S. M. (2014). Sexual modulation of testosterone: Insights for humans from across species. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 1, 93-123.

Muller, M. N., Marlowe, F. W., Bugumba, R., & Ellison, P. T. (2009). Testosterone and paternal care in East African foragers and pastoralists. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 276, 347-354.

Stulp, G., Buunk, A. P., Pollet, T. V., Nettle, D., & Verhulst, S. (2013). Are human mating preferences with respect to height reflected in actual pairings. PloS one, 8, e54186.

van Anders, S.M., Steiger, J., & Goldey, K.L. (2015). Effects of gendered behavior on testosterone in women and men. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Wood, W., & Eagly, A. H. (2012). Biosocial construction of sex differences and similarities in behavior. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 55-123.