Attention

Pre-Suasion: Before You Try to Persuade Someone…

Why controlling the moment BEFORE your message is critical.

Posted October 18, 2016 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Robert Cialdini is the author of Influence, a book which has been, well, very influential. It has sold over 3 million copies. Influence is not only a fun read, but it is brim-full of some of the best research-backed advice you will ever hear (I talked about Cialdini’s 6 principles of influence earlier, and I also described some of his classic research findings when I nominated him as one of psychology’s geniuses).

But Cialdini is not one to rest on his laurels. This month, he has been traveling around the world, and appearing on PBS, to talk about his brand new book Pre-suasion.

The title Pre-suasion gives away the central premise: A beautifully crafted persuasive argument can completely fail, even backfire, if you don’t control what is happening in the moment before you deliver that persuasive argument. In other words, you have to pre-suade before you can per-suade.

Q: What did one job applicant do just before his interview to magnify the chances he would land the job?

I'll answer the question about the pre-suasive job applicant below. But for now, let's consider one of Cialdini’s favorite illustrations of his central premise. It comes from a study of a seemingly innocuous factor in consumer decisions—the backgrounds of web pages. In that study, marketing researchers Naomi Mandel and Eric Johnson set up two different webpages for a store selling sofas. All the information on both webpages was the same, except in one case, the background was fluffy clouds, and in the other, it was pennies. People who saw the fluffy clouds were more likely to search for comfortable sofas, and were willing to pay a few bucks more for comfort. People who saw the exact same ad with pennies in the background, on the other hand, were more likely to pay attention to price, and to prefer a less costly sofa (Mandel & Johnson, 2002).

Another illustration comes from a series of studies conducted by Cialdini and his former graduate students (Griskevicius et al. 2009). They demonstrated that advertisements using simple and classic persuasion principles—such as popularity and scarcity—can fail miserably, or succeed wonderfully, depending on the information that immediately precedes the advertisement.

In that research, people in one condition read a product review about a restaurant described as “the most popular restaurant” at which “many people gathered.” They were told that “if you want to know why everyone gathers here for a great dining experience, come join them at the Bergamot Café.” In another condition, the Bergamot Café was instead described as a destination for a chosen few: “a unique place off the beaten path” that was a “one-of-a-kind place... yet to be discovered by others.” Those subjects read that: “if you’re looking for a great dining experience different from any other, look no further than the Bergamot Café.”

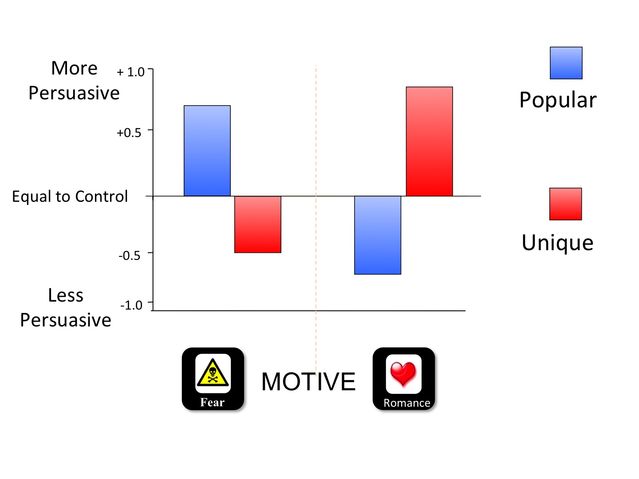

When asked whether they’d actually enjoy going to the Bergamot Café, people’s responses depended on what had been going on just before they read the restaurant review. Some of them had just watched scenes from a scary movie (The Shining); others had just watched a romantic movie (Before Sunrise).

The results are shown in the figure:

Compared to people who were experiencing no emotion, people who had just seen the scary movie were positively influenced by the appeal to popularity, but they were actually turned off by the appeal to uniqueness. People who were feeling romantic, on the other hand, had just the opposite reaction—they were turned off by popularity, and attracted to the out-of-the-way place far from the bustling crowds. This suggests that when advertisers think about “product placement,” they should pay attention not only to how much viewership a program has, but to what its content is. Placing an ad about a popular product in the middle of a romantic movie, or placing an ad for a scarce and unique product in a scary crime drama, could actually depress sales.

Overview of Pre-suasion

In Part I: Cialdini pays a lot of attention to attention. For example, he devotes one chapter to the question: What grabs our attention? And one to the question: What holds our attention? The answer is not the same thing.

In Part II, Cialdini goes into the various ways persuasive messages can profit by association. One chapter is titled “Persuasive Geographies: All the right places, all the right traces.” Where someone is when they hear your argument is also critically important in determining whether they will be pre-suaded or not.

In Part III, Cialdini devotes several chapters to the question of how to optimize “pre-suasion,” and also tackles some of the ethical issues involved in trying to persuade (and pre-suade) others.

Punchline:

A central premise of Cialdini’s argument is that, if you want to persuade someone to contribute to your cause, vote for your candidate, or hire you for a job, it is important not only to develop a strong persuasive appeal, but to be sure the audience's attention is focused in the right direction during the moment just before you present your appeal.

One of his favorite examples of pre-suasion answers the question I posed earlier:

Q: What did one job applicant do just before his interview to magnify the chances he would land the job?

A: He asked the interviewers “What was it that led you to bring me in for this interview?”

This worked, Cialdini argues, because it masterfully focused the interviewer’s attention onto the strengths of the applicant right at the start, and simultaneously led the interviewer to focus on the company’s motivation to hire someone with his talents, instead of starting in on his potential weaknesses.

In the style of his earlier book on influence, Pre-suasion is full of interesting real-world examples and research studies that back up Cialdini’s insightful intuitions. It’s a good read, and full of engaging material for those who teach social psychology, marketing, or political science, or for those of us who sometimes try to persuade other people to help us, hire us, or agree with our opinions.

Related Blogs:

- The 6 principles of social influence

- Who are psychology’s geniuses? Part II

- Six degrees of social influence

- And the year’s best paper in consumer psychology is...

Link to PBS coverage of Cialdini and Pre-Suasion:

References

Cialdini, R.B. (2009). Influence: Science and practice (5th edition). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Cialdini, R.B. (2016). Pre-suasion: A revolutionary way to influence and persuade. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Griskevicius, V., Goldstein, N. J., Mortensen, C. R., Sundie, J. M., Cialdini, R. B., & Kenrick, D. T. (2009). Fear and loving in Las Vegas: Evolution, emotion, and persuasion. Journal of Marketing Research, 46 (3), 384-395.

Mandel, N., & Johnson, E. J. (2002). When web pages influence choice: Effects of visual primes on experts and novices. Journal of consumer research, 29 (2), 235-245.