Bias

The Curious Case of Confirmation Bias

The concept of confirmation bias has passed its sell-by date.

Posted May 5, 2019 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for data that can confirm our beliefs, as opposed to looking for data that might challenge those beliefs. The bias degrades our judgments when our initial beliefs are wrong because we might fail to discover what is really happening until it is too late.

To demonstrate confirmation bias, Pines (2006) provides a hypothetical example (which I have slightly modified) of an overworked Emergency Department physician who sees a patient at 2:45 a.m.—a 51-year-old man who has come in several times in recent weeks complaining of an aching back. The staff suspects that the man is seeking prescriptions for pain medication. The physician, believing this is just one more such visit, does a cursory examination and confirms that all of the man's vital signs are fine—consistent with what was expected. The physician does give the man a new prescription for a pain reliever and sends the man home—but because he was only looking for what he expected, he missed the subtle problem that required immediate surgery.

The concept of confirmation bias appears to rest on three claims:

- First, firm evidence, going back 60 years, has demonstrated that people are prone to confirmation bias.

- Second, confirmation bias is clearly a dysfunctional tendency.

- Third, methods of debiasing are needed to help us to overcome confirmation bias.

The purpose of this essay is to look closely at these claims and explain why each one of them is wrong.

Claim #1: Firm evidence has demonstrated that people are prone to confirmation bias.

Confirmation bias was first described by Peter Wason (1960), who asked participants in an experiment to guess at a rule about number triples. The participants were told that the sequence 2-4-6 fit that rule. They could generate their own triples and they would get feedback on whether or not their triple fit the rule. When they had collected enough evidence, they were to announce their guess about what the rule was.

Wason found that the participants tested only positive examples—triples that fit their theory of what the rule was. The actual rule was any three ascending numbers, such as 2, 3, 47. However, given the 2-4-6 starting point, many participants generated triples that were even numbers, ascending and also increasing by two. Participants didn’t try sequences that might falsify their theory (e.g., 6-4-5). They were simply trying to confirm their beliefs.

At least, that’s the popular story. Reviewing the original Wason data reveals a different story. Wason’s data on the number triples (e.g., 2-4-6) showed that six of the 29 participants correctly guessed the rule on the very first trial, and several of these six did use probes that falsified a belief.

Most of the other participants in that study seemed to take the task lightly because it seemed so simple—but after getting feedback that their first guess was wrong, they realized that there was only one right answer and they'd have to do more analysis. Almost half of the remaining 23 participants immediately shaped up—10 guessed correctly on the second trial, with many of these also making use of negative probes (falsifications).

Therefore, the impression found in the literature is highly misleading. The impression is that in this Wason study—the paradigm case of confirmation bias—the participants showed a confirmation effect. But when you look at all the data, most of the participants were not trapped by confirmation bias. Only 13 of the 29 participants failed to solve the problem in the first two trials. (By the fifth trial, 23 of the 29 had solved the problem.)

The takeaway should have been that most people do test their beliefs. However, Wason chose to headline the bad news. The abstract to his paper states that “The results show that those [13] subjects, who reached two or more incorrect solutions, were unable, or unwilling, to test their hypotheses.” (p. 129).

Since then, several studies have obtained results that challenge the common beliefs about confirmation bias. These studies showed that most people actually are thoughtful enough to prefer genuinely diagnostic tests when given that option (Kunda, 1999; Trope & Bassok, 1982; Devine et al., 1990).

In the cognitive interviews I have conducted, I have seen some people trying to falsify their beliefs. One fireground commander, responding to a fire in a four-story apartment building, saw that the fire was in a laundry chute and seemed to be just beginning. He believed that he and his crew had arrived before the fire had a chance to spread up the chute—so he ordered an immediate attempt to suppress it from above, sending his crew to the 2nd and 3rd floors.

But he also worried that he might be wrong, so he circled the building. When he noticed smoke coming out of the eaves above the top floor, he realized that he was wrong. The fire must have already reached the 4th floor and the smoke was spreading down the hall and out the eaves. He immediately told his crew to stop trying to extinguish the fire and instead to shift to search and rescue for the inhabitants. All of them were successfully rescued, even though the building was severely damaged.

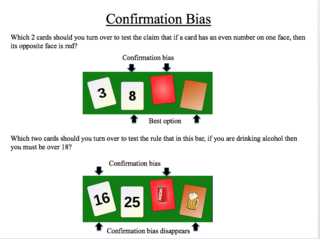

Another difficulty with Claim #1 is that confirmation bias tends to disappear when we add context. In a second study, Wason (1968) used a four-card problem to demonstrate confirmation bias. For example: Four cards are shown, each of which has a number on one side and a color on the other. The visible faces show 3, 8, red and brown. Participants are asked, "Which two cards should you turn over to test the claim that if a card has an even number on one face, then its opposite face is red?” (This is a slight variant of Wason’s original task; see the top part of the figure next to this paragraph.)

Most people turn over cards two and three. Card two, showing an “8,” is a useful test because of the opposite face is not red, the claim is disproved. But turning over card three, “red,” is a useless test because the claim is not that only cards with even numbers on one side have a red opposite face. Selecting card three illustrates confirmation bias.

However, Griggs and Cox (1982) applied some context to the four-card problem—they situated the task in a tavern with a barkeeper intent on following the law about underage drinking. Now the question took the form, “Which two of these cards should you turn over to test the claim that in this bar, 'If you are drinking alcohol then you must be over 19'?" Griggs and Cox found that 73 percent of the participants now chose “16,” and the beer—meaning the confirmation bias effect seen in Wason's version had mostly vanished. (See the bottom part of the figure above.)

Therefore, the first claim about the evidence for confirmation bias does not seem warranted.

Claim #2: Confirmation bias is clearly a dysfunctional tendency.

Advocates for confirmation bias would argue that the bias can still get in the way of good decision making. They would assert that even if the data don’t really support the claim that people fall prey to confirmation bias, we should still, as a safeguard, warn decision-makers against the tendency to support their pre-existing beliefs.

But that ploy, to discourage decision-makers from seeking to confirm their pre-existing beliefs, won’t work because confirmation attempts often do make good sense. Klayman and Ha (1987) explained that under high levels of uncertainty, positive tests are more informative than negative tests (i.e., falsifications). Klayman and Ha refer to a “positive test strategy” as having clear benefits.

As a result of this work, many researchers in the judgment and decisionmaking community have reconsidered their view that the confirmation tendency is a bias and needs to be overcome. Confirmation bias seems to be losing its force within the scientific community, even as it echoes in various applied communities.

Think about it: Of course we use our initial beliefs and frames to guide our explorations. How else would we search for information? Sometimes we can be tricked, in a cleverly designed study. Sometimes we trick ourselves when our initial belief is wrong. The use of our initial beliefs, gained through experience, isn’t perfect. However, it is not clear that there are better ways of proceeding in ambiguous and uncertain settings.

We seem to have a category error here—people referring to the original Wason data on the triples and the four cards (even though these data are problematic) and then stretching the concept of confirmation bias to cover all kinds of semi-related or even unrelated problems, usually with hindsight: If someone makes a mistake, then the researchers hunt for some aspect of confirmation bias. As David Woods observed, "The focus on confirmation bias commits hindsight bias."

For all these reasons, the second claim that the confirmation tendency is dysfunctional doesn’t seem warranted. We are able to make powerful use of our experience to identify a likely initial hypothesis and then use that hypothesis to guide the way we search for more data.

How would we search for data without using our experience? We wouldn’t engage in random search because that strategy seems highly inefficient. And I don’t think we would always try to search for data that could disprove our initial hypothesis, because that strategy won’t help us make sense of confusing situations. Even scientists do not often try to falsify their hypotheses, so there’s no reason to set this strategy up as an ideal for practitioners.

The confirmation bias advocates seem to be ignoring the important and difficult process of hypothesis generation, particularly under ambiguous and changing conditions. These are the kinds of conditions favoring the positive test strategy that Klayman and Ha studied.

Claim #3: Methods of debiasing are needed to help us to overcome confirmation bias.

For example, Lilienfeld et al. (2009) asserted that “research on combating extreme confirmation bias should be among psychological science’s most pressing priorities.” (p. 390). Many if not most decision researchers would still encourage us to try to debias decision-makers.

Unfortunately, that’s been tried and has gotten nowhere. Attempts to re-program people have failed. Lilienfeld et al. admitted that “psychologists have made far more progress in cataloguing cognitive biases… than in finding ways to correct or prevent them.” (p. 391). Arkes (1981) concluded that psychoeducational methods by themselves are “absolutely worthless.” (p. 326). The few successes have been small and it is likely that many failures go unreported. One researcher whose work has been very influential in the heuristics and biases community has admitted to me that debiasing efforts don’t work.

And let’s imagine that, despite the evidence, a debiasing tactic was developed that was effective. How would we use that tactic? Would it prevent us from formulating an initial hypothesis without gathering all relevant information? Would it prevent us from speculating when faced with ambiguous situations? Would it require us to seek falsifying evidence before searching for any supporting evidence? Even the advocates acknowledge that confirmation tendencies are generally adaptive. So how would a debiasing method enable us to know when to employ a confirmation strategy and when to stifle it?

Making this a little more dramatic, if we could surgically excise the confirmation tendency, how many decision researchers would sign up for that procedure? After all, I am not aware of any evidence that debiasing the confirmation tendency improves decision quality or makes people more successful and effective. I am not aware of data showing that a falsification strategy has any value. The Confirmation Surgery procedure would eliminate confirmation bias but would leave the patients forever searching for evidence to disconfirm any beliefs that might come to their minds to explain situations. The result seems more like a nightmare than a cure.

One might still argue that there are situations in which we would want to identify several hypotheses, as a way of avoiding confirmation bias. For example, physicians are well-advised to do differential diagnosis, identifying the possible causes for a medical condition. However, that’s just good practice. There’s no need to invoke a cognitive bias. There’s no need to try to debias people.

For these reasons, I suggest that the third claim about the need for debiasing methods is not warranted.

What about the problem of implicit racial biases? That topic is not really the same as confirmation bias, but I suspect some readers will be making this connection, especially given all of the effort to set up programs to overcome implicit racial biases. My first reaction is that the word “bias” is ambiguous. “Bias” can mean a prejudice, but this essay uses “bias” to mean a dysfunctional cognitive heuristic, with no consideration of prejudice, racial or otherwise. My second reaction is to point the reader to the weakened consensus on implicit bias and the concession made by Greenwald and Banaji (the researchers who originated the concept of implicit bias) that the Implicit Association Test doesn’t predict biased behavior and shouldn’t be used to classify individuals as likely to engage in discriminatory behavior.

Conclusions

Where does that leave us?

Fischhoff and Beyth-Marom (1983) complained about this expansion: “Confirmation bias, in particular, has proven to be a catch-all phrase incorporating biases in both information search and interpretation. Because of its excess and conflicting meanings, the term might best be retired.” (p. 257).

I have mixed feelings. I agree with Fischhoff and Beyth-Marom that over the years, the concept of confirmation bias has been stretched—or expanded—beyond Wason’s initial formation so that today it can refer to the following tendencies:

- Search: to search only for confirming evidence (Wason’s original definition)

- Preference: to prefer evidence that supports our beliefs

- Recall: to best remember information in keeping with our beliefs

- Interpretation: to interpret evidence in a way that supports our beliefs

- Framing: to use mistaken beliefs to misunderstand what is happening in a situation

- Testing: to ignore opportunities to test our beliefs

- Discarding: to explain away data that don’t fit with our beliefs

I see this expansion as a useful evolution, particularly the last three issues of framing, testing, and discarding. These are problems I have seen repeatedly. With this expansion, researchers will perhaps be more successful in finding ways to counter confirmation bias and improve judgments.

Nevertheless, I am skeptical. I don’t think the expansion will be effective because researchers will still be going down blind alleys. Decision researchers may try to prevent people from speculating at the outset even though rapid speculation is valuable for guiding exploration. Decision researchers may try to discourage people from seeking confirming evidence, even though the positive test strategy is so useful. The whole orientation of correcting a bias seems misguided. Instead of appreciating the strength of our sensemaking orientation and trying to reduce the occasional errors that might arise, the confirmation bias approach typically tries to eliminate errors by inhibiting our tendencies to speculate and explore.

Fortunately, there seems to be a better way to address the problems of being captured by our initial beliefs, failing to test those beliefs, and explaining away inconvenient data—the concept of fixation. This concept is consistent with what we know of naturalistic decision making, whereas confirmation bias is not. Fixation doesn’t carry the baggage of confirmation bias in terms of the three unwarranted claims discussed in this essay. Fixation directly gets at a crucial problem of failing to revise a mistaken belief.

And best of all, the concept of fixation provides a novel strategy for overcoming the problems of being captured by initial beliefs, failing to test those beliefs, and explaining away data that are inconsistent with those beliefs.

My next essay will discuss fixation and describe that strategy.

References

Arkes, H. (1981). Impediments to accurate clinical judgment and possible ways to minimize their impact. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 49, 323-330.

Devine, P. G. Hirt, E.R.; Gehrke, E.M. (1990), Diagnostic and confirmation strategies in trait hypothesis testing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 952–63.

Fischhoff, B. & Beyth-Marom, R. (1983). Hypothesis evaluation from a Bayesian perspective. Psychological Review, 90, 239-260.

Griggs, R.A., & Cox, J.R. (1982). The elusive thematic-materials effect in Wason’s selection task. British Journal of Psychology, 73, 407-420.

Klayman, J., & Ha, Y-W. (1987). Confirmation, disconfirmation, and information in hypothesis testing. Psychological Review, 94, 211-228.

Klein, G. (1998). Sources of power: How people make decisions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kunda, Z. (1999). Social cognition: Making sense of people.Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lilienfeld, S.O., Ammirati, R., & Landfield, K. (2009). Giving debiasing away: Can psychological research on correcting cognitive errors promote human welfare? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 390-398.

Oswald, M.E., & Grossjean, S. (2004). Confirmation bias. In R.F. Rudiger (Ed.) Cognitive illusions: A handbook on fallacies and biases in thinking, judgement and memory. Hove, UK: Psychology Press.

Pines, J.M. (2006). Confirmation bias in emergency medicine.Academic Emergency Medicine, 13, 90-94.

Trope, Y., & Bassok, M. (1982), Confirmatory and diagnosing strategies in social information gathering. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 22–34.

Wason, P.C. (1960). On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 12, 129-140.

Wason, P.C. (1968). Reasoning about a rule. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 20, 273-281.