Personality

3 Everyday Factors Help Raise Borderline Personality Life Quality

New research uses qualitative and quantitative analysis to find key factors.

Posted May 14, 2022 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- Researchers followed a group of BPD patients a year after treatment to look at key day-to-day factors associated with good outcomes.

- Overall, researchers identified two main classes best fit the data on function: functioning well and functioning poorly.

- Three themes that distinguished differences in the groups were the love of self and others, work/study contribution, and daily life stability.

By Grant H. Brenner

As the veil of stigma lifts, with each new revelation of the impact of mental illness on life and death, public interest and sophistication around personality and relationships are rising exponentially. Media portrayals, celebrity behavior, depictions of troubled superheroes and villains, and journalistic analysis are increasingly psychologized, with an exponentially-increasing sophistication.1

Not So Sexy

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) often captures the public eye, typically with romanticized depictions of troubled heroes and anti-heroes struggling with demons within a dramatically moral context. The reality is less sanguine, despite flashes of excitement and stimulation.

BPD is characterized by chronic feelings of emptiness, emotional instability, tormenting fears of abandonment and rejection, identity disturbance with an unstable sense of self, difficulty controlling impulses leading to reckless behavior, difficulty controlling anger with aggression, consistently intense interpersonal relationships with dysfunctional “either/or” thinking (“splitting” and “projection”), suicidal and/or self-destructive thoughts and behaviors, and periods of transient paranoia and dissociation.

Per the National Institute of Mental Health NIMH, personality disorders are common, affecting over 9 percent of people–and 1.4 percent have BPD. The rate of BPD is high in mental healthcare settings, affecting 12 percent of outpatients, nearly 25 percent of those admitted for psychiatric treatment, and almost 30 percent in forensic populations.

Borderline personality disorder often occurs alongside depression, substance use problems, abuse and trauma history, difficulty with personal and professional functions, and other factors, elevating the risk for serious health problems and other adverse outcomes.

Treatment can be effective and includes intensive therapy (e.g., dialectical behavior therapy) in a structured treatment setting with adjunctive medication management and emerging therapies (e.g., transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), ketamine), treatment of co-occurring problems, and enduring behavioral change (e.g., changes in self-care approach and routines).

Going beyond symptomatic relief, understanding the longer-term lifestyle-related factors associated with doing better or worse following care is critical for sustained well-being.

How can we get a handle on these long-term risk and protective factors? In their paper in the journal Personality and Mental Health, Grenyer et al. (2022) reported findings from following a group of patients treated for BPD a year after completing treatment to look at key day-to-day factors associated with good outcomes.

Learning From Patients

Researchers followed 48 patients with BPD treated in an outpatient mental health setting with proper evaluation, short-term intervention, and referral for ongoing personality disorder treatment.

One year after completing the program, they were interviewed by a trained research psychologist who was not involved in their prior care. In addition to demographic factors, participants were rated on a series of measures.2

Participants were asked to report subjectively how much they thought they had improved and participated in semi-structured interviews asking how they were doing. Themes from these interviews were analyzed with standard qualitative analysis, allowing not just for quantitative findings based on numerical ratings but also to derive recurring, generalizable themes from actual patient experiences.

Two Post-Treatment Paths for Borderline Personality Disorder

Overall, researchers identified two main classes best fit the data on function: functioning well and functioning poorly. These two groups were similar in demographics, baseline function, and social support.

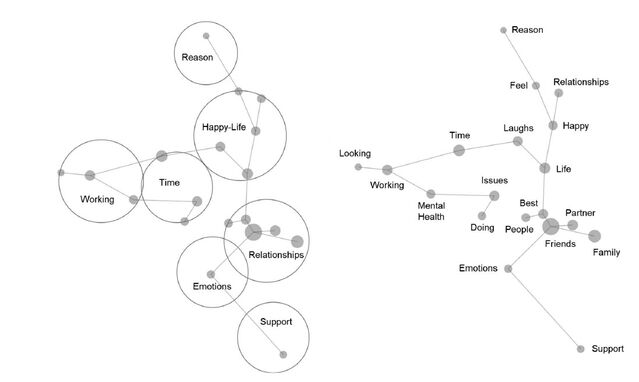

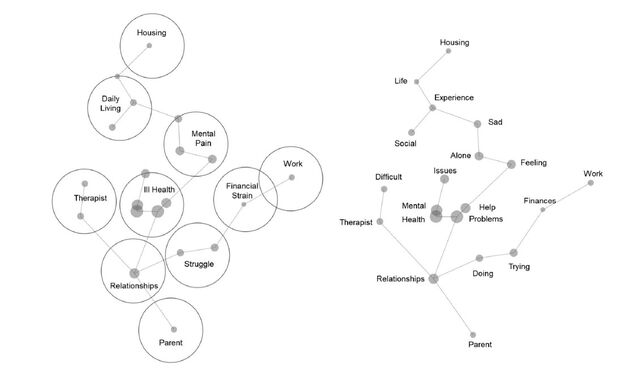

Illustrations from the original study provide an at-a-glance view of key differences:

A year later, participants in the functioning well group reported greater employment and occupational function and more robust social connections. They lost fewer workdays and were reportedly more productive when they did work. Those in the functioning well group reported better clinical ratings and subjective improvement across all dimensions.

Those in the functioning poorly group reported minimal progress with a corresponding negative view of progress.

Distilling Personal Stories

Analysis of the semi-structured interviews revealed three overarching themes that distinguished the functioning well from the functioning poorly group:

1. Love of Self and Others. People functioning well reported better quality close relationships and more enduring relationships through adversity. They reported that being a parent was important in being loved and loving others. Having increased child well-being in this group and providing meaning and purpose–taking care of others was a strong motivator. They were more likely to have more positive self-appraisal.

Those in the functioning poorly group reported greater relationship instability and loss. They reported they had reduced support from friends and family. Additionally, they were more likely to describe having people in their lives who were also struggling without reporting the resilience-enhancing benefits of supportive relationships, as well as fewer connections.

2. Making a Contribution Through Work and Study. Those in the functioning well group noted the importance of purposeful activity, paid, and volunteer work. Being productive and successful enhances self-efficacy and self-esteem. Participants emphasized the importance of meaning in work, for example helping children in need, as a key factor.

In the functioning poorly group, while some reported work satisfaction, more reported work was a challenge area. Participants noted difficulty doing well in school or holding down a job; others noted difficulty balancing school and work obligations, suggesting difficulty with time management or self-organization and the intrinsic effort required.

Some also reported social isolation and avoidance interfering with feeling good, for example, staying home from school due to depression or social anxiety leading to lagging performance. Difficulty getting motivated was a common problem.

3. Stability in Everyday Life. Folks in the functioning well group described that day-to-day life was less disrupted by stress and unresolved trauma. While traumatic experiences came up, they were easier to accept and were less disruptive emotionally. Stressors (e.g., dealing with financial issues) were seen as necessary to deal with and get through rather than as insurmountable obstacles or proof that everything was bad.

They were prone to value and mention positives, including appreciating having basic needs met and working steadily, having family and friends, and enjoyed being productive with a positive outlook on continuing to build in the future.

By contrast, those in the low functioning group experienced stressful events as crises, with difficulty coping adaptively (e.g., problem-solving, reappraisal) and a tendency to interpret events negatively and anticipate worst-case scenarios (i.e., catastrophizing, all-or-nothing thinking, and over-generalization). It was harder for them to stay in the moment and contextualize stressors within a bigger context. They reported having more difficulty securing basic needs like housing and financial security.

Being Proactive

This study highlights several important aspects relevant for people with borderline personality disorder, with broader implications about what factors contribute to overall life satisfaction. This research with an outpatient psychiatric population found that one year after treatment, patients tended to be doing quite well or quite poorly; there was no middle group.

While this study did not directly measure underlying factors related to personality and resilience or report on co-morbid illnesses such as depression and complex PTSD, these likely play a critical role in determining who does better and who is worse.

Catching who is at risk before discharge from treatment and developing an ongoing plan would likely convert some from poor to well functioning, particularly with a focus on bolstering drivers of the three themes of love of self and others, making contributions through work and study, and stability in everyday life.

Improving personality factors affecting productivity and satisfaction, including higher neurosis, lower conscientiousness and agreeableness, and diminished openness, could also improve long-term quality of life.

Identifying patients at risk for relapse would allow for close monitoring and early intervention following discharge: those with co-morbid psychiatric or addiction problems; with reduced resilience as evidenced by lower support, self-efficacy, and difficulty coping; with fewer external resources; and in unstable relationships would likely benefit from psychoeducation about when to seek help and intermittent check-ins. It also suggests that additional treatment might have been useful following discharge from the main program.

Future research can build on these findings to enhance outcomes. Individuals can use this knowledge to help guide self-assessment and make positive changes toward greater well-being and health.

To find a therapist, visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

References

1. BPD symptom severity; psychological distress (Mental Health Index) with five dimensions of depression, anxiety, positive affect (emotion), loss of behavioral/emotional control and psychological well-being; the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHO-QOL) scale; Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF–a standard psychiatry estimate of overall function); and the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO-DAS), looking at problems with daily functions (e.g. work, activities in the home, etc.).

2. Even popular children’s shows depict clear themes of mental illness, personality disorders, substance and alcohol use issues, and complex traumatic representations in individuals and families including the intergenerational transmission of trauma. More often than note, they seek to raise awareness and model healthy as contrasted with unhealthy behaviors. At the same time, kids are seeing more dysfunction in the world around them.

Grenyer, B. F. S., Townsend, M. L., Lewis, K., & Day, N. (2022). To love and work: A longitudinal study of everyday life factors in recovery from borderline personality disorder. Personality and Mental Health, 1– 17. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmh.1547

Note: A Psychiatry for the People post ("Our Blog Post") is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice. We will not be liable for any loss or damage caused by your reliance on information obtained through Our Blog Post. Please seek the advice of professionals, as appropriate, regarding the evaluation of any specific information, opinion, advice, or other content. We are not responsible and will not be held liable for third party comments on Our Blog Post. Any user comment on Our Blog Post that in our sole discretion restricts or inhibits any other user from using or enjoying Our Blog Post is prohibited and may be reported to Sussex Publishers/Psychology Today. Neighborhood Psychiatry. All rights reserved.