Play

A Visit to a Swedish Preschool

A Personal Perspective: Lessons from the outdoors for American educators.

Posted May 26, 2022 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Key points

- Swedish preschool children spend an average of 90 minutes outside on "bad weather" days and 6 hours outdoors on nice days.

- Forest preschools are becoming increasingly popular, where children spend most (if not all) of their school days outside - rain or shine.

- A visit to a Swedish forest preschool was eye-opening and inspiring for a group of American honors college students (and their professors).

I recently returned from an academic trip to Stockholm, Sweden. This trip was part of a class for honors college students entitled, “A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Play.” I co-taught this class with a colleague of mine who is a play therapist. We chose to visit Sweden after learning about the significance that members of this culture place on play, time spent outdoors, and a close relationship with nature.

In preparation for the visit, students read selections from There’s No Such Thing as Bad Weather by Linda Åkeson McGurk. The author of this book is from Sweden but is raising her children in the United States. Throughout the book, she discusses the differences she observes in child-rearing between the two countries. She also explains several cultural traditions among the Swedish when it comes to school and play for children that inspired us to travel there to observe them first hand.

McGurk also details the preschool curriculum in Sweden. The 20-page long national curriculum features the word “play” 13 times and the word “nature” 6 times. She notes that the preschool curriculum in Sweden doesn’t just promote play in all activities – it also establishes children’s “legal right to play and learn outside.” For urban preschools that lack access to natural environments or large school yards, they can take their students to public green spaces on foot or via public transportation. In the city of Stockholm, the city’s public parks and gardens cover 40% of Stockholm’s area (a total of nearly 10.5 square miles of parks), and include over 300 playgrounds.

Preschoolers in Sweden spend about an hour and a half outside every day – on a bad-weather day in the winter. On a nice day in the summer, they spend about 6 hours outside. For children who attend forest preschools, the children spend the majority of the school day outdoors all year-round, regardless of the weather. This video shows an example of a forest school in Denmark, and nicely illustrates the teaching philosophy and practices of this type of school, along with the ways in which children are able to play and behave.

There are more than 180 forest preschools in Sweden. Fortunately, we were able to visit one of those while on our trip – an “I Ur Och Skur” – “Rain or Shine” – preschool named Mulleborg Preschool. As can be seen from their (translated) sign, their motto is – where the children play, discover, and laugh – out in nature! (Mulleborg Förskolan dar barnen leker, upptäcker och lär – ute i naturen!) When we arrived, we were given a tour of their school yard, and then taken on a journey into the forest with the class of 3- to 4-year-olds.

The school yard itself was eye-opening, and stood out to us as contrasting sharply with what we typically see on U.S. school grounds. We passed a canoe leaned up against the side of the building, because students can take canoe rides with a teacher at a nearby pond in warmer weather (or they can ice skate on the pond on winter days). In the yard, children were freely swinging from a rope swing, and there were several climbing structures that looked to be homemade (rather than pre-fabricated). There were also firepits, the foundation for a large tee-pee, small shelters, tools, toys, and lots of space.

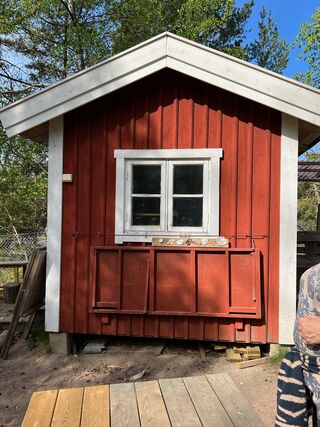

The teachers showed us a tool shed where children are often permitted to experiment (under supervision) with hammers, nails, saws, and loose boards. On the side of this shed was an array of small pieces of trash nailed to a board. These trash items had been buried by the children in the ground and were dug up 6 months later so that the children would see how little deterioration had taken place. This lesson in the effect that pollution has on the earth was simple yet powerful. In fact, when we did go to the forest, children picked up several pieces of trash along the way, unprompted.

The forest was about a 10 minute walk from the school building, and the children were allowed to ‘lead’ the way. They had stop points a few times along the route so that they did not ever venture out of the teachers’ line of sight, but it did not feel like the teachers were ever hovering over or herding the children. As we began our ascent into the forest, the children stopped at a pile of rocks, where Mulle – an imaginary forest troll that inspires children to care about nature – had left a small basket of raisins for them. One child immediately picked up the basket and began to distribute them to everyone (including us!), and the children sang a song of thanks to Mulle.

After arriving at the summit, the children spread out foam mats, were treated to a story (Eric Carle’s “The Hungry Caterpillar”), and then played a memory game using objects in nature. After a snack, they were allowed to play freely for about 30 minutes. There were no visible boundaries or limitations. The teachers say that the kids know about an “invisible fence” – they must be able to see the teachers at all times. If they want to climb trees or piles of sticks, they are free to do so. The teachers will not help them - otherwise, “they won’t know how to climb down.” The teachers emphasized how the children need to build their strength, coordination, motor skills, and confidence by figuring things out on their own.

As the children played in the forest, we repeatedly noted the lack of any aggression or hostility (compared to observations we had made at American playgrounds before traveling to Sweden). The children cooperated, included one another, shared flowers, berries, rocks, and sticks with one another, and took turns seamlessly. While some of their good behavior may have been related to the fact that we were observing, the teachers told us that they have been working really hard on being respectful to one another and to nature.

The children freely explored, happily picked berries and flowers, inspected bugs, bounced on branches, and made stick forts. They climbed, jump, ran, hopped, and pretended. Perhaps most obvious – they were all happy! They even brought back "bouquets" as souvenirs to bring home.

The day that we visited Mulleborg was sunny and about 70 degrees Fahrenheit. However, the next day it was forecast to rain and be in the 50’s – and the teachers assured us that nothing would change about the routine. The children, they said, actually often prefer when it rains, because they like the “rivers” it makes, and they like to splash and play in the mud. They have washing machines and spare clothes at the school, so messy play is encouraged!

Imagine how much different American society might look if our children all attended forest preschools? Or even just “regular” preschools, but had a minimum of an hour and a half outdoors every day? Might we grow into adults who, like the Swedish children that we observed, would share, cooperate, lack aggression, and just, in general, be happier? Perhaps American parents, teachers, and administrators should learn from these Swedish children - get outside, trust yourself, respect nature and one another, get sweaty, get muddy, and just have fun!