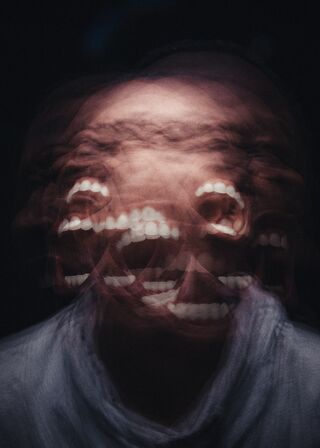

Trauma

The Deeper Reason You May Not Like Anyone

Those with unresolved trauma may find it hard to feel safe around others.

Posted September 7, 2022 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- According to the theory of inferred attraction, we like people whom we think like us.

- If we don't feel safe around people, we won't like them.

- To like people more, it's important to savor signals of safety from them.

No one can be trusted.

No new friends.

I don’t like people.

One question I grappled with while writing my book Platonic is: If we are an inherently social species, why are some of us so antisocial?

One reason is that we struggle to feel valued by others. But why would that impact how much we like people? According to the theory of inferred attraction, people like people who they think like them. When strangers interacted, one study found that how much one liked the other depended on how liked they felt in the interaction. If we like people when we think they like us, then when we assume no one likes us, we won't like anyone.

It’s hard to like people when we don’t feel valued by them. In fact, one study found that feeling valued is the number-one thing people look for in friends. Similarly, avoidantly attached people—who isolate themselves because they tend to think other people can’t be trusted and don’t have their best interests in mind—report experiencing less joy in interactions. When we feel rejected, we self-protect—withdrawing, getting aggressive, acting critically, disliking—ultimately making us cynical toward others.

But if we don’t like people, it may not be because no one is safe, but rather, because of past trauma, we struggle to absorb that anyone could be safe. Past trauma leads us to scan for current threats that crudely mimic it. A frown, a perceived slight, or even a tone can poke at this trauma, leading us to react as if the original wound had reoccurred. With unhealed trauma, it may feel like we are only safe around perfect people, lest we superimpose our perpetrator onto them. And because no one is perfect, no one is safe. And because no one is safe, we don’t like anyone.

The Path Forward

Our past wounds impel us to scan for signals of threats and ignore those of safety. Thus, to feel safe around others and like them more, we must scan for signs of safety.

Rick Hanson, a psychologist who studies neuroplasticity, created the H.E.A.L. model to help people rewire their brains to feel safer and happier. It involves, essentially, attending to and savoring moments of safety that our threat-saturated brain would typically ignore. Hanson argues that what is state becomes trait, or, in other words, the more we scan for safety, the more our brain will do so automatically.

To practice H.E.A.L., intentionally attend to what’s safe. Don’t let good moments pass by without focusing on them. Here are the first three steps of H.E.A.L. (the last is optional, so I'll review only the first three).

-

Have a beneficial experience. Signals of safety don’t have to be substantial, like someone driving you to the hospital after you broke your arm. They can be tiny—someone smiled at you, held the door, validated your feelings, flashed you kind eyes, texted you to check in, congratulated you, or even liked your social media post. Notice these experiences.

-

Enhance the experience by doing things like pausing to savor the joy of it or upping the intensity of the positive feeling. Soften and open to its positivity. Let it stir something in you.

-

Absorb the positive experience by picturing it melting into your body.

There is research suggesting that H.E.A.L. rewires the brain. When an experience is intensified, our body releases more norepinephrine, which makes our brain more malleable and makes us more likely to remember things. Another review indicates that the more rewarding an experience is (such as when we savor it), the more our bodies release dopamine, which alters our brain structure and fosters new memories. Hanson’s research found that people who practiced H.E.A.L. felt more positively and less negatively for months after employing the model.

If someone smiles, savor the warmth it ignites, and visualize yourself installing the warmth in your body. If a friend initiates plans, focus on their care until it stirs positive emotions in you; picture yourself absorbing that care. The next time you are hugged, stop to imbibe the love in their embrace, feel its glow in your heart, and visualize that glow growing in you. Don’t let any signal of safety go unnoticed.

H.E.A.L. will require intention and practice before feelings of safety happen automatically. But the more you do it, the safer you’ll feel. You’ll eventually feel safe enough to relinquish your walls and to like, and possibly even love, people.

For more on the science of healing our relationships, you can read my book Platonic: How the Science of Attachment Can Help You Make—and Keep—Friends.