Beauty

How the Global Beauty Ideal Pressures Women to Be "Perfect"

#EverydayLookism and cleavage shaming.

Posted February 19, 2021

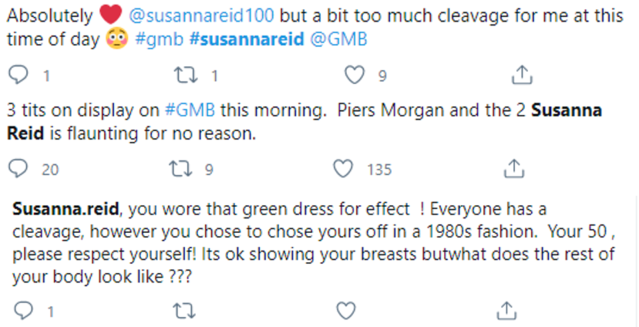

In January 2021, British television personality Susanna Reid’s breasts became a news story. Sites reported how her cleavage had distracted or aggravated viewers. Twitter users also began commenting on her cleavage, with posts including:

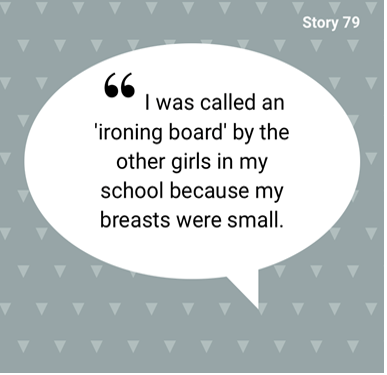

Breast-shaming, sadly, happens a lot. Holly Willoughby was attacked for a low-cut dress she wore presenting "Dancing On Ice." And it’s not just those with big breasts who "flaunt" them who are shamed. Those with small breasts get it in the neck—well just below—too. Actresses Alicia Vikander, Sharifah Sakinah, and Madeleine Ang have all been trolled for being "flat-chested."

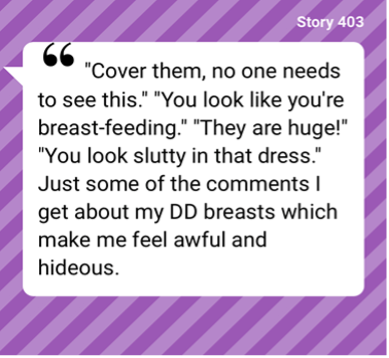

If you’re big-breasted you might be told to "cover up," "stop being slutty," or told that their body is "inappropriate." If you’re small-breasted, you may be called "unwomanly" or "childlike." Basically, if you have breasts, you can’t win.

As the global ideal becomes more demanding there is more pressure not just to dress your breasts right, but to have the right breasts. In Perfect Me, Heather argues that thin with curves is part of the global beauty ideal—for many women, this often means implants! She says “…breast size can vary…pertness is desirable across sizes.”[1] Pertness is a tough call, typically available only to the young, and to those who haven’t breastfed. It’s not surprising many women are not happy with our breasts.

A 2020 Breast Size Satisfaction Survey (BSSS) by Professor Viren Swami of Anglia Ruskin University surveyed “18,541 women in 40 countries." It showed that “only 29 percent of women were satisfied” with their current breast size; 48 percent “wanted larger breasts” and 23 percent “wanted smaller breasts.” Professor Swami reports that breast size dissatisfaction can lead to poor “physical and psychological well-being,” including low self-esteem, “anxiety, shame, or embarrassment.” These negative effects are heightened when others make negative comments about our bodies.

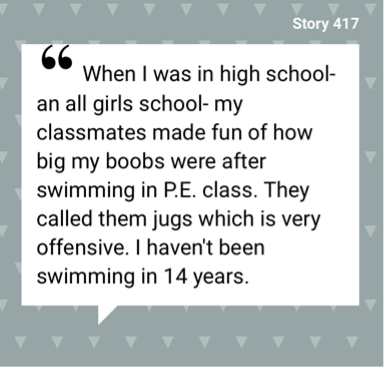

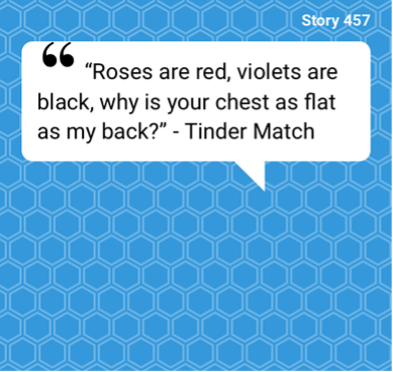

It’s not just those in the public eye who receive cleavage shaming comments. In our increasingly visual and virtual culture, we are all subject to the pressure to be perfect, or "good enough." And breasts seem impossible to get right as the #EverydayLookism stories show:

These anonymous stories show what a common form of body shaming this is; deeply gendered and exceptionally hurtful. Yet body-shaming is widespread and part of our everyday experience. We know that these comments hurt, but often we find it hard to explain why.

The #EverydayLookism campaign aims to make body-shaming easier to address. By giving us the words to explain why body-shaming is discriminatory and harmful, we are naming lookism. If our bodies are our selves then body-shaming is people shaming. Calling out lookism shifts this shame from the individual onto the perpetrator. We don’t want to live in a culture where this is ok. By sharing anonymous stories of lookism, we can kick back against body shaming and take the focus off bodies.

To find out more about the campaign, read the anonymous stories or to submit your own, go to everydaylookism.bham.ac.uk.

Helen Ryland, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Department of Philosophy, University of Birmingham.

Jessica Sutherland, Research Assistant and Global Ethics Ph.D. student, Department of Philosophy, University of Birmingham.

Heather Widdows, John Ferguson Professor of Global Ethics, Department of Philosophy, University of Birmingham.

References

[1] Widdows, H. (2018) Perfect Me: Beauty as an Ethical Ideal. Oxford. Princeton University Press., p.20.