Stress

The Dynamics of Conflict Between Parent and Child

The LSCI Conflict Cycle sheds light on how to de-escalate problem situations.

Posted February 20, 2019

Since 1991, Life Space Crisis Intervention (LSCI) has been offered as a professional training program for educators, counselors, psychologists, social workers, youth workers, and other professionals working with challenging children & adolescents. In recent years, the LSCI Institute has worked to translate its trauma-informed, brain-based, relationship-building concepts to the need of parents and caregivers. In an excerpt from the LSCI Institute's new book, Parenting the Challenging Child: The 4-Step Way to Turn Problem Situations Into Learning Opportunities, the LSCI Conflict Cycle™ is introduced, explaining the circular and escalating dynamics of conflict between parents and children and offering important insights about the parent’s role in either fueling problem situations or halting them before they spiral out of control.

Excerpt from Chapter 1: The 3 Foundations of LSCI

Foundation 3: THE CONFLICT CYCLE

To get a rich understanding of the Conflict Cycle, we will begin by considering how adults and children typically perceive, think, feel, and behave in response to stressful events and problem situations. An awareness of these elements of the Conflict Cycle will give us important insights into why kids sometimes behave in troubling ways.

Perception

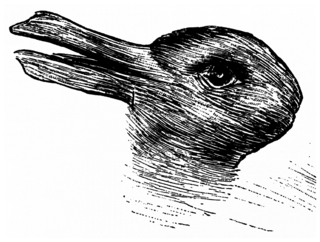

In general, adults know that there are many ways to perceive the world. For example, if we were to look at the image below, some of us would see a duck and some of us would see a rabbit.

Hopefully, when asked to consider if the other perception was valid, we would acknowledge that while our point of view is accurate, the other person’s point of view is also correct. Based on our life experiences, we can acknowledge that other people’s points of view have merit and that two people can have opposing ways of looking at the world and still both be “right.”

We also know that stress can heavily influence our perceptions when it comes to the way we look at problem situations. As a result, we are usually willing to listen to alternative viewpoints. Sometimes, we even reconsider our own!

Young people often have a much more difficult time accepting alternate points of view. In times of stress, kids can become especially concrete about their perceptions. Parents and caregivers can make the mistake of believing that their kids are simply being stubborn when they insist that their perception of an event is the only correct one. The idea that the child “knows the truth about what happened but won’t admit it,” can trigger a hostile reaction from adults. At this point, both the adult and the child are perceiving each other from a place of hostility.

LSCI skills guide parents and caregivers to recognize that:

1. We all have unique ways of perceiving our world. Knowing how a child perceives a situation is always the starting point for teaching an alternate perception. We have to make time to find out how the child perceives an event before we can offer new information.

2. A child’s ability to consider other points of view has to do with the availability and approachability of an adult who will listen and dialogue with the child.

3. Parents and children both enter conflict situations with a sense of being “right.” Insisting that someone else change their point of view usually only results in increased hostility and defensiveness about the original position.

The LSCI approach offers a solution to the tendency of adults and kids to become locked in rigid and opposing ways of perceiving an event.

Thinking and Feeling

In our earlier discussion of the second foundation of LSCI (How LSCI Skills Help Soothe the Brain and Ready Kids for Conversation), we thoroughly examined the brain-based origins of stressed out thoughts and overwhelming feelings. The Conflict Cycle paradigm shows us how the perceived stress of an event can trigger a set of amygdala-driven thoughts and feelings which, in turn, drive a young person’s unwanted or unacceptable behaviors.

Behavior

As we look at each individual component of the Conflict Cycle, it is important to note that behavior is usually the first part of the Conflict Cycle that gets our attention. There are no flashing lights to warn a parent about an alarming set of perceptions or an amygdala-driven cluster of thoughts and feelings in a child. Rather, it is usually a disruptive behavior(s) that first makes us aware of a problem.

It's also important for parents and caregivers to think of their child’s poor behavior as a symptom. Behavior is a reflection of the unique perceptions, thoughts and feelings the child is experiencing over a particular event. LSCI challenges traditional thinking about why kids show unwanted behavior. We often hear that kids act out because they want power, control, or attention. It's true that we all want some power and control over our environment. Most of us crave some attention and human interaction. These are good things. If kids didn't want them, we'd really be worried about them. As illogical as it might seem, the problems that kids create are usually an attempt to gain some power, control or attention. What’s more, their acting up and acting out is rarely just random. Usually, it is predictable. (Fecser, 2013). If you think of your child who challenges you the most, you can probably predict with a good deal of accuracy what kind of problem he’s going to get into next. Most kids behave in repetitive patterns.

Knowledge of the LSCI Conflict Cycle guides parents and caregivers to understand how certain stressful situations trigger predictable perceptions, thoughts, feelings, and unwanted behaviors. If we can predict it, we can prevent it. In other words, adults can use the Conflict Cycle as a roadmap to anticipate troubling behavior and intervene to help kids develop more positive ways of thinking and better coping skills to deal with overwhelming feelings. Over time, consistent use of the LSCI approach helps parents prevent the troubling behavior from occurring again and again.

Adult Response

As parents and caregivers, if we are not thoughtful, purposeful and aware, we will react to a child’s poor behavior as if it is occurring in isolation—forgetting that there are a whole set of perceptions, thoughts, and feelings that drive it. We may resort to rote punishment or hurtful, impulsive responses that damage our relationship with our child.

Keep in mind: The adult’s response is the only element of the Conflict Cycle that parents have any control over. If our ultimate goal is to teach young people that they have choices when it comes to their behavior, we must begin by role modeling positive choices of our own, particularly in terms of how we respond to our kids’ unwanted behaviors.

Read the real-life example below of one parent’s effective response to her child’s challenging behavior:

A parent arrived at school to pick up her 4th grade daughter for a scheduled doctor’s appointment. As the daughter approached her mother in the school hallway, she began to cry and yell, “I don’t want to go! This always happens. You always make me leave!”

The mother could feel the stares of her daughter’s teacher as well as the school Nurse and Counselor who were all witnessing the situation. She felt the pressure of their judgment both on her parenting and on her loud, disruptive child. She realized right away that she had two choices:

1. She could use a traditional disciplinary approach and firmly tell her daughter to quiet down in the hallway and stop her disrespect immediately.

She felt justified that this would be an appropriate parental response but she also knew that for her daughter, this would have been the next stressful event and would have triggered even more upsetting thoughts and feelings in the emotional part of her daughter’s brain. Things would have gotten worse for sure.

2. Option 2 was to try to tap into her daughter’s rational brain in an effort to get more of a logical response.

First, she got down on her daughter’s level and hugged her. She said, “You are really upset right now.” Her daughter took one long sob, then she melted into her mother’s arms.

Just at that moment, the school nurse, who had heard all of the commotion in the hallway, joined in the conversation with a well-intentioned, but too quick rational brain response: “Your mom is trying to keep you healthy. What would happen if you didn’t get a flu shot?” she asked.

The child stiffened and started crying and yelling at her mother all over again.

Her mother gave her time. She continued to hug her. She wiped her tears. She used validating words instead of becoming defensive: “You feel like I am picking you up from school too early and you are missing your recess time with your school friends. This happened last month too and you are feeling sad all over again.”

The child softened and made eye contact with her mother. She nodded and said, “Yes, I am so sad.”

Within two minutes of this soothing interaction with her mother, the young girl regained her composure. As she walked out of the building, she was respectful, relieved, and ready to go to her doctor’s appointment.

In this situation, Option 1 may have been appropriate, but it would have been a missed opportunity for the parent to connect and communicate with her child, to help her daughter practice skills for calming down, and to practice connecting language to emotion.

Does that mean a parent should allow her child to “get away with” the disrespectful behavior that was initially displayed in the school hallway? No. There is a time for setting standards and communicating with young people about acceptable behaviors—but this parent used her knowledge of the LSCI Conflict Cycle as a roadmap to understand that it would be more effective to wait to address these important issues when her child was more in control and more receptive to learning.

Understandably, troubling behaviors by a child—especially those that seem to come “out of the blue” can create big reactions in adults and we don’t all respond as well as this mother did. Unfortunately, too often parents take on a child’s feelings and even mirror the child’s behaviors. They may raise their voices, threaten punishment, or say hurtful things. This negative adult reaction, in turn, becomes the next stressful event for the child and creates a new turn of a Conflict Cycle. Self-defeating power struggles between parents and children continue to ensue. Understanding the Conflict Cycle is the first line of defense against reinforcing a child’s irrational beliefs and engaging in these no-win dynamics.

Even parents and kids with the most positive of relationships get into Conflict Cycles sometimes. Effective parenting is not the absence of conflict entirely, but rather knowledge of how stressful situations can activate the emotional part of the brain and prevent kids (and adults!) from using their thinking brain to effectively manage the conflict.

The LSCI Conflict Cycle offers a visual guide to understand—and therefore help prevent—escalating power struggles between parents and children. In the next two chapters, you will learn the LSCI skills needed to help you de-escalate the intense thoughts and feelings that can be triggered by stressful situations. Ultimately, you will learn new ways to effectively disengage from no-win conflicts with kids. The goal of LSCI is to make young people feel safe and supported enough to choose to talk about their feelings with a parent rather than to act them out in disruptive or destructive ways.

Signe Whitson is the Chief Operating Officer of The LSCI Institute and author of Parenting the Challenging Child: The 4-Step Way to Turn Problem Situations Into Learning Opportunities. For more, visit lsci.org

References

Long, N., Fecser, F. & Wood, M. (1991). Life Space Crisis Intervention: Talking with Students in Conflict. Texas: ProED, Inc.

Whitson, S. (2019). Parenting the Challenging Child: The 4-Step Way to Turn Problem Situations Into Learning Opportunities. Hagerstown, MD: The LSCI Institute.