Persuasion

Schopenhauer Talks Back

The old pessimist gives advice on how to win an argument.

Posted January 8, 2016

Life is short and truth works far and lives long: let us speak the truth. ~ Schopenhauer

Textbooks of social psychology have chapters on “persuasion” or “attitude change,” but no chapter on how to win an argument (e.g., Myers, 2013). Yet, many of our conversational efforts are disputatious. We feel that we are in the right and we want the other to concede this. The other feels the same way, however, and so the stage is set for frustration, anger, and resentment. Idealist psychologists would rather ignore this. As self-professed realists, they think that the truth is out there and that rational individuals will converge on this truth by using evidence and logic. Were it only so!

Ironically, most mainstream social psychologists assume that people’s minds are shot through with irrationality, and that their task is to show just how and in what way they are irrational. Should we then not have a social psychology that teaches us how to win arguments by exploiting others’ irrationalities? To suggest as much raises ethical concerns and social psychologists want to be on the side on the angels. The crisis of the social-psychological conscience is apparent in the textbook chapters on persuasion and attitude change. A typical study presents research participants with arguments regarding some issue (e.g., a tuition increase). The arguments are pretested to be strong or weak, and they are delivered by an attractive or an unattractive source, or with or without repetition. There are many contextual aspects that can be varied in the presentation of the arguments (see DeBono & Harnish, 1988, for an example). Then the participants’ attitudes are measured again and the difference between pretest and posttest attitude reflects the amount of persuasion that has occurred. In the standard paradigm, there is no debate. At best, the researchers infer that the participants have debated the issue in their own heads before either changing their attitude or sticking to their guns. The psychology of persuasion is unidirectional. It consists of the study of the effectiveness of arguments under a variety of circumstances. Occasionally, researchers and textbook authors note how persuasion techniques targeting irrational responding can be exploited for political or business gain (e.g., using attractive communicators or repetition to hide the weakness of the arguments), but these studies say little about how me may seek to refute those who actually have a case.

What is the reader of this research to take home from this? What lessons can they learn to improve their own persuasive success? When all the main effects and the statistical interactions of the research are considered, the most robust effect is still the strength of the arguments. Sometimes, the effect of strong arguments is overshadowed by ‘peripheral cues,’ such as source attractiveness, repetition, or vivid imagery, but it is rarely reversed. If you want to persuade anyone to change her attitude about anything, and if little else is known about the context, it is better to have strong as opposed to weak arguments. This should not be surprising on the assumption of rationality.

The strong-argument approach reflects psychologists’ concern for the truth. A strong argument is by definition one that brings out the true characteristics of whatever is at stake. Strong arguments are persuasive inasmuch as the audience cares about the truth and would feel ashamed if it didn’t. However, people often care mainly about winning an argument, whatever its truth value may be. The standard research design sheds no light on this because it does not allow participants to talk back. The strong-argument theory of persuasion only allows for the possibility that people may not be paying attention, but it does not expect them to argue their own interests.

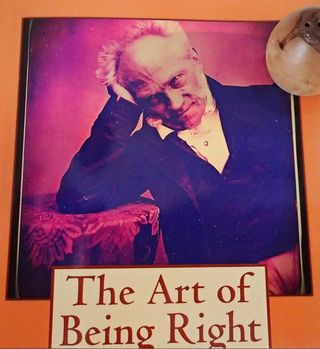

This is where Arthur Schopenhauer comes in. In 1831, he wrote an essay entitled The art of being right. The premise of his essay was that most people are rechthaberisch, they want to be acknowledged as being right. To win this acknowledgment from individuals who disagree and who themselves seek acknowledgment is difficult. To win the day requires a sharp wit, and Schopenhauer shows the way.

Schopenhauer introduces the concept of dialectic as “the art of disputation,” in contrast to logic, which is “the science of the laws of thought, that is, of the method of reason.” Dialectic is akin to rhetoric, as it is concerned with persuasion primarily and truth only secondarily (if at all). “To logic we should assign objective truth as far as it is merely formal, and [. . .] dialectic should be confined to the art of gaining one’s point.” Schopenhauer motivates the use of dialectic by noting that “it is easy to say we must yield to truth, without any prepossession in favor of our own statement; but we cannot assume that our opponent will do it, and therefore we cannot do it either.” And “even when a man has the right on his side, he needs dialectic in order to defend and maintain it.”

Schopenhauer concludes his introduction with a critical observation. Even if the opponent seeks to refute our arguments with illogic, trickery, and non-sequiturs (i.e., with dialectic), we must share some common ground of rationality. “In every disputation or argument on any subject we must agree about something; and by this, as a principle, we must be willing to judge the matter in question. We cannot argue with those who deny principles: Contra negantem principia non est disputandum.” To judge whether the opponent agrees with us on basic principles is the first, and perhaps most difficult psychological task. Often, however, pigheadedness and intransigence are revealed only while the dispute is already in full swing. If it comes to such a revelation, rational individuals cut their losses and walk away.

Before presenting his 38 dialectic “stratagems” for winning an argument, Schopenhauer observes that refutations are either ad rem (about the issue) or ad hominem (about the person); and they are either direct or indirect, respectively showing that the opponent’s thesis is not true or that it cannot be true. This is not the place to review all 38 stratagems (see Wikipedia for the full list). Let’s take a look at some of the stratagems to get a feel for Schopenhauer’s approach. The first stratagem is extension. The goal is to give the opponent’s claim the broadest possible interpretation while keeping one’s own as narrow as possible. If the opponent allows this to happen, you can attack some peripheral aspect of his argument and then assert that you refuted the whole thing. Suppose, for example, that your sibling claims that your mother was a terrible parent. You know your sibling is referring to mother’s domestic relationship with you kids when you were little. You counter by extension and point out that she saved her own inheritance to finance your college education.

Stratagem III is a variant of extension. Here you seek to refute an opponent’s claim by pointing to some other particular case where it does not hold and then “triumphantly declare” (as Schopenhauer would put it) that the entire argument is false. Schopenhauer’s example is delightful. “I maintained that [Hegel’s] writings were mostly nonsense; or, at any rate, that there were many passages in them where the author wrote the words, and it was left to the reader to find a meaning for them.” Attempting to use stratagem III, his opponent pointed out that Schopenhauer should not have praised the Quietists because they too had written much nonsense. Schopenhauer parried by clarifying that he had praised the Quietists for their honest business dealings, not for their insightful writing.

Stratagems I and III, as well as many others, in one way or another change the subject or redefine what the opponent claims to allow refutation. We sometimes see variants of these stratagems in reviews and other evaluations, where the opponents focus on the weakest part of the argument under the assumption that if they can refute that, they have shown the entire work to be flawed. Schopenhauer therefore counsels to keep one’s claims narrow and well defined. Unfortunately, this self-protective strategy comes at the price of being timid and conservative. Sometimes – e.g., in science – we need bold and broad new claims if we are to advance.

Stratagems VI and XII are about begging the question or petitio principii. Begging the question is a difficult concept and often confused with ‘raising the question.’ To beg the question is to assume – as a premise – that which is to be shown. Schopenhauer does not give good examples for VI and his treatment of XII is only about the choice of words. He advises us to use metaphors most favorable to our case. His examples are euphemisms (e.g., the phrase “through influence and connection” hides the true meaning of “bribery and nepotism”). In my blogging, I have found that question-begging is popular among those who argue for the existence of god. To say, for example, that god reveals his existence in our belief in his existence begs the question of whether he exists.

Stratagem XVIII directly asks you to change the subject (mutatio controversiae, see above). Writes Schopenhauer: “If you observe that your opponent has taken up a line of argument which will end up in your defeat, you must not allow him to carry it to its conclusion, but interrupt the course of the dispute in time, or break it off altogether, or lead him away from the subject, and bring him to others.” Skill and subtlety are required here because we may expect that the opponent is on a roll, sensing the successful completion of the attack. Psychologically speaking, this stratagem requires the effective manipulation of attention. In its most elegant form, the mutatio controversiae leaves the opponent in the belief that the topic has not changed all, while you know very well that it has and that you have dodged defeat.

Strategem XXVI is the retorsio argumenti, the turning of the tables, which Schopenhauer regards as brilliant – when it can be accomplished. The goal is to claim (and convince the opponent) that the evidence he introduced actually refutes his point. Schopenhauer does not provide a good example, so I will make one up. Suppose his opponent claims that Hegel was a great philosopher because the King of Prussia put so much faith in him. Schopenhauer might reply that the King’s confidence is evidence for Hegel’s mediocrity (or worse), given that the King is a known nincompoop.

On the home stretch, Schopenhauer gets into what is now well-trodden social-psychological territory. Stratagem XXX introduces the argumentum ad verecundiam, or appeal to authority as opposed to reason. Subsumed in this is the appeal to majority belief. Schopenhauer claims that “there is no opinion, however absurd, which men will not readily embrace as soon as they can be brought to the conviction that it is generally adopted.” Why? People are lazy. “They will sooner die than think.” He adds that “to speak seriously, the universality of an opinion is no proof, nay, it is not even a probability, that the opinion is right.” Here, the sage errs. Authority and majority are in fact, under most circumstances, probabilistic cues to truth. If there is no other information, it is in fact best to follow the experts or the majority (Gigerenzer, Hertwig, & Pachur, 2011).

Schopenhauer eventually turns to the dialectic of last resort: rudeness. Stratagem XXXVIIII states that “a last trick is to become personal, insulting, rude, as soon as you perceive that your opponent has the upper hand.” This may seem strange because rudeness will not convince the opponent that she has been bested. Instead, she will just consider you rude. Schopenhauer seems to be aware of this when he notes that the utility of this stratagem is merely a “gratification of vanity.” [1]

In the end one wonders how Schopenhauer himself felt about the whole exercise. His assessment that people are by and large self-centered and irrational is fair enough. It corresponds to everyday perception and much of social-psychological research. In this presentation of the 38 stratagems he is inconsistent in that he advises us to resort to these stratagem when we cannot rely on logic (or rely on logic being respected by the opponent), but at the same time showing how opponents tried a stratagem on him and how he in turn refuted them (see, e.g., our discussion of stratagem III).

It is quite obvious that Schopenhauer was ambivalent about “the art of being right;” he was aware of its amoral and deceptive aspect. Nevertheless – or precisely because of that – we may wish to see more research on the dialectics of argumentation.

[1] The rudeness stratagem comes in many forms. Schopenhauer does not explore all its variants – I think because it sickened him. One variant that I think is of particular psychological interest does not even involve rudeness proper (which includes ad hominem insults), but the strategic display of anger or offense-taking. Research has shown, for example, that displays of anger do in fact improve outcomes in negotiation – at least in the short term (van Kleef, de Dreu, & Manstead, 2004). This is probably so because the display of anger is associated with dominance and social power, which suggest submission as the prudent response. Offense-taking does not signal social power unambiguously; indeed, it is often used by low-power individuals or groups in an effort to claim power. Current examples of this strategy can be found on college campuses. Either way, these emotion-based strategies stifle reasonable debate. If ‘successful,’ they may shut an opponent up, but not convince him. That would be a Pyrrhic victory at best, or, as Schopenhauer would put it, a gratification of vanity.

DeBono, K., & Harnish, R. J. (1988). Source expertise, source attractiveness, and the processing of persuasive information: A functional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55, 541-546.

Gigerenzer, G., Hertwig, R., & Pachur, T. (2011). Heuristics: The foundations of adaptive behavior. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Myers, D. (2013). Social psychology, 11th edn. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Van Kleef, G. A., De Dreu, C. K. W., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2004). The interpersonal effects of anger and happiness in negotiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 57-76.

For a more recent introduction to rhetoric as used in argumentation, I recommend Chaim Perelman's (1982) The realm of rhetoric. London: University of Notre Dame Press.

Note. The epigraph suggests that Schopenhauer cared about truth first and foremost. This suggests that he wrote The Art in an ambivalent frame of mind and why he wrote it in an acidulous style.

Other posts on communication

3 more 4 good measure

Post-Schopenhauerian conversation-killing stratagems abound. Here are 3:

[1] My first academic mentor, Wulf-Uwe Meyer [may God sanctify his bones, as Zorba would say] used to say "I do not understand this" in response to obtuse or abstruse talks. This made life easy for him - as long as no one would conclude that he was stupid, but he was a German Universitätsprofessor after all - and his tactic reliably put the presenter on the defensive. His technique, subtle in its simplicity, is underused. Just try it at random times during your day, and be amazed at the results. You are probably reluctant for fear of being called stupid. This is unlikely to happen, though. Trust me. And if it does, respond with "Are you calling me stupid!?" It is now your opponent who has a lot of explaining to do.

[2] If you remember the "Sopranos," you may remember the episode in which Tony returns to the gang from a stint in a hospital. His roommate was a paleontologist who explained to Tony the smallness of man on a geological scale. Tony related this news excitedly to his cronies. Christopher Moltisanti, his simple-minded lieutenant, took the wind out of Tony's sails with one simple 5-word sentence delivered in dead-pan: "I don't feel that way."

[3] Ask questions and never answer questions put to you. Fictional detective Lennie Briscoe did this to a fault in the TV classic Law and Order. His unwavering adherence to this technique had an unsettling effect on me as a viewer but not on his TV interlocutors, but then again, they were as unreal as was Lenny. Again, the Lenny technique is up for being tried out and consequences being observed and savored.

Tautology

I came upon the following tautology in a text on folk psychology.

There is privileged access in that actors normally know the reasons for which they acted, because the very action was performed on the grounds of and in light of those reasons.

'That actors know their reason' is to be explained. The explanation is that they act only if they have reasons - which presumably they know. Without tautology one might say: "Sometimes people have reasons for their actions; and sometimes they don't." But that would just replace tautology with triviality.

When I presented this clip to a friend, this friend agreed that the statement is a tautology, and added "I am sure [the author] had a reason for writing it this way because why else would [he or she] have done it?" And here the circle closes.