Autism

Is a Gluten-Free Diet Beneficial For Autistic Children?

Exploring facts and controversies surrounding the use of gluten-free diets.

Posted January 8, 2023 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Many autistic young persons experience gastrointestinal challenges and restricted food intake, which can be very concerning for their families.

- Families are often curious about whether diets impact their loved ones’ autistic characteristics and bowel health.

- Gluten-free and casein-free diets are among the most frequently trialed and controversial dietary interventions for autistic children.

Many autistic young persons experience gastrointestinal challenges and restricted food intake, which can be very concerning for their families (Baspinar, 2020). Some of their gastrointestinal challenges can be attributed to atypical sensory processing such as preferences for restrictive food types (Baspinar, 2020) as well as be associated with anxiety (Mazurek et al., 2013).

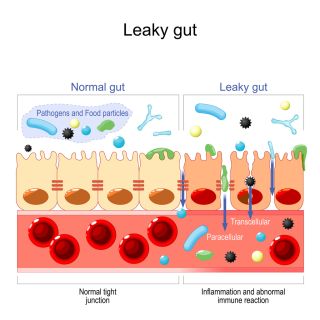

In general (despite inconsistent results), many studies find that children on the autism spectrum have higher rates of increased intestinal permeability (leaky gut) than their neurotypical peers (Tarnowska et al., 2021), as well as digestive imbalances such as reduced gut microbial taxonomic diversity (Yap et al., 2021).

Given the focus many families place on diet and digestion due to the above concerns, many parents are naturally curious about whether diets impact their loved ones’ autistic characteristics, or at least their bowel health and associated immune health (Rudzki and Szults, 2021), with gluten-free and casein-free diets being amongst the most frequently trialed and controversial dietary interventions (Tarnowska et al., 2021).

What is gluten?

According to Biesiekierski (2017), gluten is “a complex mixture of hundreds of related but distinct proteins, mainly gliadin and glutenin.” Gluten can be used as an additive for foods other than grain to help food hold shape, and can be found in thickeners, medications, meats, and many other food products. The particular properties of gluten are dependent on the ratio of gliadin and glutenin (Biesiekierski, 2017).

For some individuals with particular genetic vulnerabilities, the breaking down of peptide sequences within the Gliadin protein is associated with adverse immune reactions that are a part of coeliac disease. However, researchers suggest that for a subset of autistic children, “increased immune reactivity to gluten” is unrelated to celiac disease and possibly related to other factors such as intestinal permeability abnormalities (Lau et al., 2013).

Gluten and ASD

In 1979, Panksepp suggested that there may be an association between the overactivity of a child’s opiate system and autistic characteristics, particularly those relating to social-emotional mechanisms. This is referred to as the opioid excess theory.

One mechanism hypothesized as contributing to overactivity of a child’s opiate system has been an increased permeability of intestinal epithelium (a leaky gut) that leaks gluten and pathogens into the bloodstream (Piwowarczyk et al., 2018). Peptides can then reach the central nervous system after crossing the blood-brain barrier (Tarnowska et al., 2021).

Another hypothesized mechanism underlying an overactive opiate system is atypical metabolism of gluten and casein (Piwowarczyk et al., 2018).

To validate the opioid excess theory, researchers explored whether there is an increased concentration of opioid peptides (components of the opioid protein) in the urine or blood plasma of autistic children.

Meta-analyses of studies concluded that there isn’t enough evidence to support the opioid excess theory, as while some studies found the concentration of opioid peptides to be higher in autistic persons, others did not (Piwowarczyk, 2018).

However, the merits of the various methods of urine and plasma analysis continue to be debated, and the heterogeneity of autism makes it challenging to generalize research results, particularly those with small sample sizes (Tarnowska, 2021).

Tarnowska et al. (2021) indicated that Tveiten et al.’s (2014) study using HPLC and tandem mass spectrometry to prevent the degradation of the peptides was in response to concerns about testing concentrations of opioid peptides in urine, at the time.

Tveiten et al.’s (2014) study, involving 335 participants, did find exogenous opioid peptides in the urine samples of autistic individuals.

Similar study mentioned in Tarnowska’s (2021) review was Sokolov et al.’s (2014) study, which found elevated levels of opioid peptide of ten autistic children, using an ELISA method of testing.

Tarnowska et al. (2021) as well as numerous other authors (e.g., Basbinar et al., 202, Piwowarczyk et al., 2018) conclude that much additional research is required, given the quantity and quality of research to date, as well as an appreciation that autism is heterogeneous and various participant samples may be limited in their generalizability.

Gluten-free and casein-free diets are widely implemented (Piwowarczyk, 2018) despite generally not being recommended due to current evidence being deemed insufficient. Potential adverse reactions in response to gluten-free and casein-free diets include increased risk of malnutrition in a population of individuals already affected by food selectivity, including reduced bone density, elevated homocysteine levels, or lowered serum folate and vitamin B (Basbina, 2020).

On the other hand, gluten-free and casein-free diets have been considered by many researchers as therapeutic for a proportion of autistic children, with significant research variability around participants’ response to these diets, ranging from beneficial to harmful, without guidance of who would benefit the most.

There continues to be a call for further investigation of the various mechanisms underlying the opioid excess theory such as research into the activity of peptidases (enzymes) that break down peptides in various samples of autistic children or intestinal permeability, and increased research into the effectiveness of interventions such as digestive enzyme therapy, for various samples of autistic children (Tarnowska et al., 2021).

Parents considering trailing gluten-free diets are advised to consult their medical practitioners about supporting them with managing risks of elimination diets such as monitoring levels of food intake and nutrients in their loved ones.

References

Baspinar B, Yardimci H. Gluten-Free Casein-Free Diet for Autism Spectrum Disorders: Can It Be Effective in Solving Behavioural and Gastrointestinal Problems? Eurasian J Med. 2020 Oct;52(3):292-297. doi: 10.5152/eurasianjmed.2020.19230. Epub 2020 Jun 4. PMID: 33209084; PMCID: PMC7651765.

Biesiekierski, J. R. (2017). What is gluten? Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 32(S1), 78–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.13703

Lau, N. M., Green, P. H. R., Taylor, A. K., Hellberg, D., Ajamian, M., Tan, C. Z., Kosofsky, B. E., Higgins, J. J., Rajadhyaksha, A. M., & Alaedini, A. (2013). Markers of Celiac Disease and Gluten Sensitivity in Children with Autism. PloS One, 8(6), e66155–e66155. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066155

Mazurek, M. O., Vasa, R. A., Kalb, L. G., Kanne, S. M., Rosenberg, D., Keefer, A., Murray, D. S., Freedman, B., & Lowery, L. A. (2013). Anxiety, Sensory Over-Responsivity, and Gastrointestinal Problems in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(1), 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9668-x

Panksepp, J. (1979). A neurochemical theory of autism. Trends in Neurosciences (Regular Ed.), 2, 174–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-2236(79)90071-7

Piwowarczyk, A., Horvath, A., Łukasik, J., Pisula, E., & Szajewska, H. (2018). Gluten- and casein-free diet and autism spectrum disorders in children: a systematic review. European Journal of Nutrition, 57(2), 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-017-1483-2

Rudzki, L., & Szulc, A. (2018). “Immune Gate” of Psychopathology-The Role of Gut Derived Immune Activation in Major Psychiatric Disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 205–205. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00205

Tarnowska, K., Gruczyńska-Sękowska, E., Kowalska, D., Majewska, E., Kozłowska, M., & Winkler, R. (2021). The opioid excess theory in autism spectrum disorders - is it worth investigating further? Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2021.1996329

Yap, C. X., Henders, A. K., Alvares, G. A., Wood, D. L. A., Krause, L., Tyson, G. W., Restuadi, R., Wallace, L., McLaren, T., Hansell, N. K., Cleary, D., Grove, R., Hafekost, C., Harun, A., Holdsworth, H., Jellett, R., Khan, F., Lawson, L. P., Leslie, J., … Gratten, J. (2021). Autism-related dietary preferences mediate autism-gut microbiome associations. Cell, 184(24), 5916–5931.e17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.10.015