Artificial Intelligence

The Simplistic Debate Over Artificial Intelligence

AI might bring doom, but so might we...if we remain independent.

Posted October 25, 2017

Man will only become better when you make him see what he is like. —Anton Chekhov

The disagreement this summer between two currently-reigning U.S. tech titans has brought new visibility to the debate about possible risks of Artificial Intelligence. Tesla and SpaceX CEO Elon Musk has been warning since 2014 about the doomsday potential of runaway AI. Along the way, Musk’s views have been challenged by many but the debate went mainstream when another billionaire celebrity CEO, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg took issue with what he believes to be Musk’s alarmist view.

This tiff of the titans is worth noting because of the high stakes and because their opposing views represent the most common schism over AI. Is it a controllable force for good, or a potentially uncontrollable force that, unless managed properly—or even shut down—places humanity at an unreasonably high risk of doom?

Of course, this debate isn’t new. Many intellectual luminaries have been deeply interested in this issue for decades, and most people are familiar with these opposing views. In 1942, Isaac Asimov published his first set of rules of robotics designed to avert Science Fiction AI rebellions. And possible dangers of AI have been explored and contrasted in Science Fiction blockbuster films, such as 2001: A Space Odyssey, the Terminator and Matrix series, Ex Machina, and many others.

Unfortunately, these depictions of AI are excessively adversarial and simplistically anthropocentric. The diametrically opposed views of Zuckerberg and Musk—at least those portrayed by media—are like the Coca-Cola and Pepsi, or mainstream republican and democrat ends of the ideological spectrum, leaving out the tastiest and most satisfying among possible or even likely outcomes.

Before considering alternatives, here is a bit of relevant context for thinking about the prevailing views, starting with the anti-AI side.

On this side, there are many AI doomsday scenarios, but the most common ones come in two basic flavors:

The Terminator scenario. AI perceives humans as a threat and launches countermeasures. The Terminator scenario might take place surreptitiously at first, with AI only launching an open offensive when it has grown powerful enough for an essentially zero-risk takeover.

The Divergence scenario. AI goals diverge from and compete with human goals. Vastly more capable and rapidly evolving AI simply pursues its goals and starves humanity of the resources needed for sustainability. This AI doesn’t view humans adversarially, it just doesn’t care about their welfare.

The primary driver of doomsday scenarios is self-improving intelligence, absent some rule(s) or control(s) that ensures friendliness to humans. Timescales for creating measurable improvements in AI might become short relative to humans, allowing rapidly improving AI to leave slowly improving humanity in its evolutionary wake. The first theoretical description for this “intelligence explosion” was published by I.J. Good:

“Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an ‘intelligence explosion,’ and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make, provided that the machine is docile enough to tell us how to keep it under control.”

The Terminator scenario is the one that most of us know best because it lends itself to wonderfully dramatic fiction and blockbuster films featuring awesome computer graphics.

The Divergence scenario sounds less threatening until you consider what life would be like if all key resources for staying alive disappeared. It is less well known but experts in potential AI threats take it very seriously.

At the other end of the ideological spectrum, Mark Zuckerberg and AI proponents believe increasingly powerful AI is important to creating the best future. They don’t necessarily view AI as a risk-free endeavor, but they believe that, over the long-haul, costs will be outweighed by benefits.

AI proponents currently have some major practical advantages over opponents. The main advantage is that smarter AI provides huge economic benefits—estimated by McKinsey and Company at $50 trillion in just the next eight years. Plus, proponents can point to actual progress. Although the current generation of AI is probably not on the cusp of an intelligence explosion, we do have self-driving cars; more precise medical diagnoses and better medical care; and countless hidden examples that are deeply embedded in the fabric of our lives.

A main problem for any pro- or anti-AI position is the inherent unpredictability of a self-improving intelligence. Our ability to control an increasingly intelligent AI in order to avert possible doomsday outcomes is often called the "AI control problem."

While I don’t think either side of this AI debate is unreasonable, there should be a third major position in this discussion (Estep and Hoekstra). This third position is that in any scenario—even those in which AI might pose a serious long-term threat—unaided human, natural intelligence (NI) also poses an unpredictable yet proven and serious threat to any possible bright future. Paradoxically, one of the frequently implied motivations for the Terminator scenario is that AI will be an astute judge of this human threat (to sustainability and the future generally), and will act defensively to neutralize it.

The reason we should always consider this perspective in the AI discussion is simple: human history (including the present) is unfortunately punctuated with atrocities marked by human complicity ranging from impotence and inaction to nefarious design and intentional harm. Wars, genocides, slavery, famines, dust bowls, extinctions and other large-scale crimes and calamities are the work of well-intentioned people—often groups of passionate ideologues who believed even during the extremes of their misdeeds that they are the good guys.

Whether or not some of these people were good or bad certainly is debatable, but this is not debatable: In many cases, things didn’t turn out as they imagined or planned. The same is true across human endeavors and predictions of the future, and science has given us insights as to why.

The evolutionary theoretic framework for understanding human cognitive limits and self-deception established by Robert Trivers, and filled in with many empirical details by Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky, and others (reviewed by Kahneman in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow) helps frame the debate about AI. This recent science allows us to follow through on Chekhov’s advice—to help us see what we humans are really like.

One reason we typically debate the risks of developing AI absent a discussion of the dangers of NI is that we have no choice; we are stuck with NI. It is the devil we know, while superintelligent AI is something we don’t yet know. Our focus on the hypothetical dangers of AI absent consideration of the proven dangers of NI might be considered a classic case of ambiguity aversion, a willingness to accept a characterized cost instead of an unknown cost, even if the latter might be far less or even zero.

And even though we don’t know what AI will be like, we think of it as the other, not part of our tribe; and we reasonably fear that it might similarly view us the same way. Because AI is so clearly not us, we would rather take our chances and bet on humanity—flaws and all—rather than put our future in the virtual hands of an alien being. We can accept a future replete with pain and suffering if it is a human future. No amount of harmony and bliss is sufficient to accept an AI future without humans.

But what if superintelligent AI is our only hope for creating a bright future? In other words, instead of AI being the means of our doom, we might be doomed without it. Let’s call this the AI Guardian scenario.

Even though NI is not likely to cause a cataclysmic doomsday for humanity, as in the Terminator scenario, it does pose a serious and ongoing threat. And now that we are armed with a much more clear scientific understanding of the human mind and how it evolved, we know that certain flaws of human perception, veracity, and cognition aren’t a result of evolutionary neglect, but result instead from uglier aspects of how evolution actually works. There is good evidence to suggest that certain human traits and behaviors like violence, deception, sexual coercion and assault, superstition and more have been favored by natural selection (see Pinker, The Blank Slate).

With such issues in mind, we should be very wary of preventing AI from taking preventive action against human intentions or actions. After all, we have yet to demonstrate that we are rationally managing our present—never mind the future. The 2016 U.S. presidential election was the most polarized in memory, and both sides seem to agree that many on the other side—in either case, a large fraction of the electorate—voted irrationally. My purpose in mentioning this is not to start a partisan political debate here, it is to show that in matters of serious consequence, and on very large scales, many of us already seem to accept that a sizable fraction of the population behaves irrationally.

There is a near-universal acceptance that investing in better AI will produce great economic benefits, though this is rarely discussed, except in terms of education. The same is true for NI. But we should not limit NI improvement strategies to education, but instead consider the full range of options that we typically consider when envisioning improvements to AI—in other words, engineering. If we improve human behavior and decision making, any doomsday scenario becomes less likely.

To plan and implement the best solution to this critical problem, we should reconsider our underlying discriminatory anthropocentricity; our us versus them perspective at the root of our fears of AI. A self-improving AI might view us in the way we view our own parents and mentors, but being far more capable it might provide assistance far beyond our current means to help ourselves. It might design and administer therapies or upgrades for us.

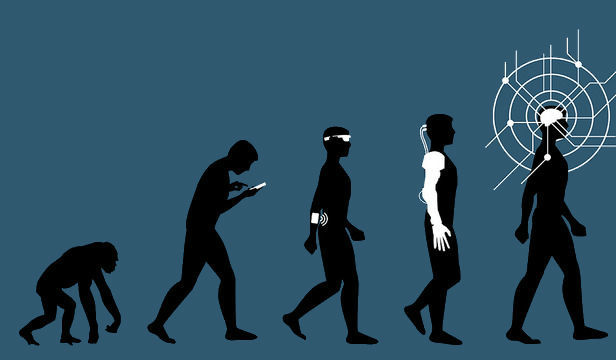

Potentially the most promising approach to preventing an AI doomsday is to continue to merge NI and AI, to become one-I. There might be no better way to ensure that an advanced intelligence will view and treat us as one of its own than to gradually eliminate the barrier between us. This approach might be the one point of agreement among the apparently divergent views of Musk, Zuckerberg, and myself. Musk's company Neuralink is working on a concept he calls "neural lace," a brain-computer interface technology, and Facebook too is reportedly working on their own brain-computer interface tech.

Conceptually radical, possible breakthrough technologies such as these are typically pitched with great conservatism, complete with an extremely narrow lens through which we are asked to view the future. Facebook suggests that their technology is being designed simply to enable people to control a cursor or keyboard with their minds. At the other end of the spectrum, Musk has envisioned much broader and radical uses of a merged intelligence. He openly admits that a main reason he has joined those of us who advocate developing AI along a path of merger and interdependency with human NI, is in large part to solve the AI control problem.

The merger of humans and AI might have this great advantage, which has rational appeal, but it might be a path we take for other, more emotional reasons. Consider our subtly implicit yet increasing desire for oneness with our tech. Our devices have become extensions of ourselves in a way they have never been before. They already stir our passions in complex ways. We feel awe and exhilaration when they perform at their peak. We feel separation anxiety when we are apart. We feel betrayal when they let us down at a critical moment. Many of us at times choose to engage with them rather than with other people, our own kind. As we routinely cradle, gaze at, and press our fingers and faces to these extensions of ourselves, there is no good reason to think we aren't feeling the initial hints of the desire to erase, completely and irreversibly, the dividing line between us and them.

References

Estep, P., & Hoekstra, A. (2016). The Leverage and Centrality of Mind. In How Should Humanity Steer the Future? (pp. 37-47). Springer International Publishing.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan.

Pinker, S. (2003). The blank slate: The modern denial of human nature. Penguin.

Trivers, R. (2000). The elements of a scientific theory of self‐deception. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 907(1), 114-131.