Psychosis

Sandra Luckow's Film "That Way Madness Lies..."

How does a family cope when one member develops a major mental illness?

Posted November 16, 2018 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

That Way Madness Lies… is Sandra Luckow’s film about her brother, Duanne, who suffers from paranoid schizophrenia. In this engaging portrait of a family, Luckow conveys powerfully the experience of trying to help a relative with major mental illness—with love, pain, persistence, and frustration. As often happens, she was dealing with several family problems simultaneously: not only with her brother’s, but also those of her parents, both of whom died during the course of filming.

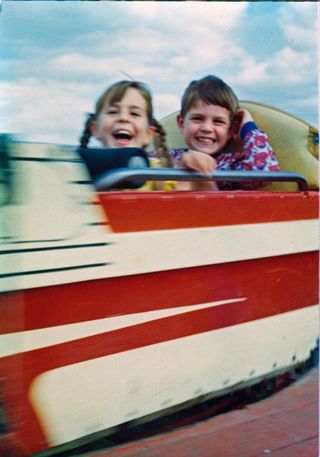

Luckow begins with images of her “eccentric and creative” family when Duanne and she were children. Her father bought and flew a gyrocopter. She herself was a ventriloquist as a child. Her mother made miniatures. Her brother was quirky even in his teens. He became a master machinist who made his living restoring classic cars. As an adult, he remained close to his parents, living near them in a house they bought for him and co-owned.

In 2009, at the unusually late age of 46, Duanne began to show signs of impaired thinking. Following his first verified psychotic episode, the family went from one crisis to the next, while Sandra tried to get treatment for her brother and protect her aging parents from the $120,000 bill charged to Duanne for an involuntary hospitalization. The hospital was in a position to demands proceeds from the house to satisfy their claim, though only from Duanne’s share of the house. A good part of the film concerns Sandra Luckow’s many legal efforts to protect her parents from losing the house. This preoccupation with the practical, financial, and legal problems a family faces seems so common when a member is living with mental illness.

When did you first realize that Duanne was suffering from a serious illness?

He began to take an obsessive interest in conspiracy theories, the New World Order, and the presumed prediction of the end of the world by the Mayan calendar. He talked about getting off the grid and wanted my parents to purchase gold. But it wasn’t until he stormed the US-Canadian border with the intention of finding and marrying a woman he knew only from the internet that it became clear he was psychotic. I am certain there was a big gap between the inception of his illness and his diagnosis at that time.

It took me a long time to realize that we were up against egregiously poor policy. My incredulous anger with these policies has fueled me now for almost a decade. Institutions hide behind the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, which protects personal health information. Since the law prevents hospitals from releasing information about a patient, even whether a particular person is in their hospital, they shut out family who could actually provide, help, resources, and valuable information. As I see it, their priority is to avoid litigation as opposed to serving their patients.

The broken mental health system basically says to someone with mental illness, “You have a right to be crazy and we don’t have a right to interfere until you become an imminent danger to yourself or others."

Can you describe how you felt during your years trying to support Duanne?

Only in this past year of showing the film have I had time to reflect on my feelings. Duanne’s illness has taken a very large toll and I am forever changed. It’s hard to be in crisis for eight years.

The major frustration, other than the contradictions of ineffective mental health policies, was being perceived and treated as Duanne’s adversary—in the beginning by his friends, and almost always by law enforcement and the medical establishment. Family members are seen as the cause of the illness and nefarious in their intentions to be involved. I am now receiving a lot of kudos about my behavior during the time of of the film, but that was not the consensus while we were living through it.

At what point did you realize you needed to make a film about your brother? What did it feel like as you put “That Way Madness Lies…” together?

When my brother was involuntarily committed to the Oregon State Hospital, the last thing on my mind was my profession, let alone making a film about him. Before he was committed for the first time, he expressed that he didn’t know whom to believe or trust about what was happening. I suggested he use his new iPhone to record so he could review what was happening later or show it to someone he trusted. I did not know how much he was recording. At the hospital, his phone was taken away because he continued to record. He asked me to retrieve the phone and look at the videos. I was devastated by what I saw: first person, unfiltered psychosis, not a portrayal or interpretation of psychosis. It was scary and confusing and surreal. I took the footage to the psychology department at Yale School of Medicine and talked with Dr. Larry Davidson. He convinced me to continue filming to give context to Duanne’s footage because it was so rare a glimpse and so valuable to understanding this illness.

My artistic process was mostly on autopilot during the filming. Once I committed to going beyond the scope of my brother’s videos, I tried to have my camera every time I went to Portland. I was holding down two university teaching jobs, living in New York City and traveling to Portland almost every six weeks. I lacked the perspective to think about many moments artistically. It was more a sense of, “Do I have a record of this moment?” When I started working with an editor, Anne Alvergue, we made a timeline of the events and began to see which were crucial but needed visuals to accompany them. It became clear I needed to follow up with Duanne’s friend Rita, who squatted in his house and caused a lot of problems, if we wanted to include her in the film. I also went back and got interviews with his two amazing friends to round out the story.

The film and my commitment to it helped me survive. Each of the many times I was overwhelmed, exhausted, exasperated, scared, confused, frustrated, depressed and angry, I would think, “This is really unbearable and bad for me, but it is good and necessary for the film.” I loved revisiting and finding the visuals to show what a talented, wacky, and wonderful existence we shared as a family. I love when viewers marvel at our creative eccentricities that were, for me part of growing up.

Your film ends when you decide to step back from your role in Duanne’s life. How has that worked? How has he been since then?

We have to remember that at its very best a documentary film is a structured representation of reality. The ending I feared was that things would reach a point where Duanne killed himself, was killed, or killed someone else. Thankfully, that has not transpired. Nor has any semblance of recovery or even insight. So it was necessary to provide an ending without being disingenuous to either my viewers or the situation. Not much has changed for Duanne. He has been in and out of the system four times since the film was finished. The police have said Duanne has used up their goodwill and they cannot look out for him any longer. I responded, “Are you saying that if Duanne is in the wrong place at the wrong time, he could be shot?” The policeman said, “Let’s hope it doesn’t come to that. But he will never be forced into treatment in Portland unless he commits a heinous crime.” That is our reality.

Many others deal with issues like those you describe. Do you have any advice for them?

My advice is that you accept that this is going to be a long haul and very difficult. Just accept it and don’t waste energy trying to find a way to circumvent the suffering. You will hit a dead-end. Accept that we don’t leave in a humane society when it comes to mental health. Every step will be dependent on what state you live in, how much money and other resources you have, how educated you are, how much support you have from your friends and community. Get down to the very hard work of accepting the reality that you or your loved one has a mental illness just as you would accept that someone has cancer or kidney failure. Then do what you can with what you have to work with. If you ever get to a point where you feel the crisis has been managed, then you become an advocate for changes in the policies that stymied you. Pete Earley, the author of Crazy: A Father’s Search Through American’s Mental Health Madness is a great example of that and my role model.

To see the trailer for “This Way Madness Lies…” click here.