Replication Crisis

The Power of Replication: A Study of Baseball Cards

A repeated study questioned the supposed effects of smiling on lifespan.

Posted September 28, 2022 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Peer review is a good sign and means a study has been vetted. But the findings may not hold up under additional research.

- We can feel more confident about a study’s findings when it has been replicated—that is, repeated in an additional study.

- A study linking smiling to baseball players' lifespans received attention, but a larger replication of that study did not replicate the first.

- When we read about a study, we should ask if it’s peer-reviewed, and then if it has been replicated.

The pandemic has made us all aware of peer review and the idea that scientific findings might be suspect in the absence of peer review. (We’ve written about peer review versus preprints before.) But what does peer review really mean?

Let’s explore a research question. Will you live longer if you smile more? A few years back, a spate of headlines promised just that: “Smiling can help you live longer,” and “For a long life, smile like you mean it.” Could the fight against aging be this simple? The experts thought so, or at least their study found evidence for this, and this surprising finding received a lot of press. But did this finding match reality?

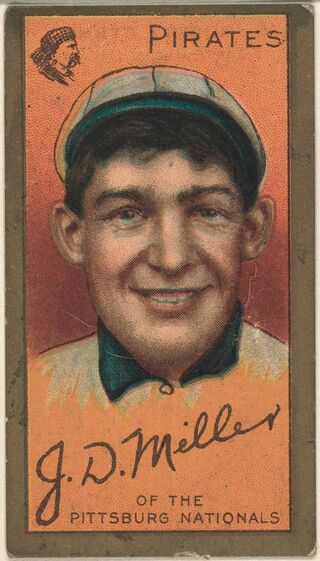

These headlines followed a publication in the prestigious journal Psychological Science titled “Smile intensity in photographs predicts longevity.” So, this suggested it was advice from experts! How did the researchers come to this conclusion? They rated 230 photos of U.S. professional baseball players from a 1952 archive as having no smile, a partial smile, or a full smile. They then examined who had died and who was still alive. Of the majority who had died, those who did not smile in their 1952 photos died around age 73, on average; those with partial smiles died at around age 75, on average; and those with full smiles died around age 80, on average. So, maybe we all just need to smile more?

Peer Review and Replication

This study was carefully conducted. More importantly, it was vetted by other scientists through an established system called “peer review” and then published in a respected, top-tier academic journal. When you read that a study has been peer-reviewed, that means that the journal editor has sent the manuscript to two or three scientists with expertise in that area. The reviewers give feedback, almost like a teacher grading a paper, and the manuscript typically doesn’t get published until the authors address the feedback from the reviewers. It’s an important safeguard for the science that affects our lives, and you should look for those words—"peer review"—when you read research findings in the news.

But peer review is far from perfect. Let’s look at the smiling study again. Several years later, another research team replicated the original study. That is, the second team used the same methods to repeat the earlier study, but the second team conducted the study with a much larger sample. In the replication, the researchers analyzed photos of all the baseball players listed in the database, not just those from 1952. This time, they did not find evidence of a link between smiling and longevity. In scientific language, they failed to replicate the original findings.

This failed replication is not an anomaly. There is currently what is sometimes termed a “reproducibility crisis” in the social sciences; sometimes, publicized findings cannot be reproduced by other researchers in other labs with other samples. (It's not just social sciences. The replication crisis also affects other sciences and medical research.)

Slippery Statistical Significance

Why does this happen? The old-school statistical analysis revolves around "magical" statistical significance levels that are rather arbitrary. The original smile study was well beyond these arbitrary levels. This may have simply been luck—bad luck since it turned out not to replicate.

But false findings are not always simply luck. A bigger problem is that it turns out to be pretty easy for researchers to play around with their analyses until a finding achieves what is known as “statistical significance.” Cut an outlying data point there, add an extra variable here, and voilà, your finding beats these levels! Such trickery seems to be somewhat common. Studies in several different fields, including psychology and political science, have documented a disproportionate number of findings that manage to just barely slide below the magical level of statistical significance.

Why? Probably because such trickery is both really easy to do and often not even done consciously. As one researcher observed, researchers often start with data that are kind of messy and then ask themselves, “How do I get from mush to beautiful results? I could be patient, or get lucky—or I could take the easiest way, making often unconscious decisions about which data I select and how I analyze them, so that a clean story emerges. But in that case, I am sure to be biased in my reasoning.” For example, a researcher might cut a few research participants because they had unusual scores or keep them even though they have unusual scores—whichever works in their favor. Some researchers only publish the findings that worked, failing to mention the ones that did not. In every study, there are dozens of tiny decisions that researchers make, and it can be tempting to make the ones that lead to statistical significance!

What does this have to do with the pandemic? It is why vaccine research, for example, involves so many layers of studies before a new vaccine is approved. It’s why research findings occasionally seem to change from month to month. Remember when masks were not recommended way back in 2020? Replication is a big part of how science works to get us the best evidence, even if it sometimes takes time.

So, here are three things you can think about when you see a new study in the news or on social media. 1) Does the source mention that the study is peer-reviewed? 2) Does it acknowledge that it’s not yet peer-reviewed (including published as a preprint), a helpful indication that they care about peer review? 3) Is there any indication that their results have been repeated (i.e., replicated) by other researchers? It is with replication that we start to trust a finding is likely real.

Even better, when considering research, look for what is called a meta-analysis or a systematic review. Both involve combining the results of many different studies on the same topic. When findings are from a meta-analysis or systematic review, replication is already built in. Because science matters to us all so much these days, it’s important to understand exactly what peer review is, why it matters, and how to ask the right questions about it!

References

Abel, E. L., & Kruger, M. L. (2010). Smile intensity in photographs predicts longevity. Psychological Science, 21(4), 542-544. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610363775

Dufner, M., Brümmer, M., Chung, J. M., Drewke, P. M., Blaison, C., & Schmukle, S. C. (2017). Does smile intensity in photographs really predict longevity? A replication and extension of Abel and Kruger (2010). Psychological Science, 29(1), 542-544. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617734315

Gerber, A., & Malhotra, N. (2008). Do statistical reporting standards affect what is published? Publication bias in two leading political science journals. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 3(3), 313-326. https://doi.org/10.1561/100.00008024

Masicampo, E. J., & Lalande, D. R. (2012). A peculiar prevalence of p values just below. 05. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 65(11), 2271-2279. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2012.711335