Intelligence

What People Don’t Want to Know About the Animals They Eat

Why committed meat-eaters often embrace willful ignorance.

Posted May 4, 2022 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Acknowledging that the animals we eat can think and feel can be upsetting.

- New work suggests that people may deal with this by avoiding information about animal minds.

- Those who have a particularly strong preference for eating meat are most likely to avoid this type of information.

This post was co-authored with Jared Piazza, Ph.D.

How can people both recognize that there are issues with meat production yet fall short in taking the necessary steps to address the problem? A growing body of research suggests that consumers often make use of relevant evidence in a strategic manner, which limits their need to take action.

Today, for example, most people acknowledge that animals reared for food are sentient and that their welfare needs to be considered. Most are also aware that there are problems with the current food system, which causes billions of animals needless suffering. A 2017 survey by the Sentience Institute found that about 70 percent of Americans reported being uncomfortable with the way farmed animals are treated, and a 2021 Viva! study found that 85 percent of Britons supported a ban on factory farming. These trends are in line with government efforts to improve the welfare of farmed animals; for example, by ending the export of live animals for slaughter.

Despite widespread awareness of the issues with meat production, though, consumers often overlook their contribution to the problem. The same 2017 survey led by Sentience Institute found that 75 percent of Americans believe that they buy “humane” meat—an impossible statistic given that the majority of meat in the U.S. is derived from factory farms. Furthermore, despite a growing awareness of the link between animal agriculture and climate change, meat-eating rates in the U.K. need to at least halve to hit the country’s 30 percent reduction target for 2030. These statistics suggest that consumers may be engaging with information strategically to avoid their behavioral implications.

My colleagues and I recently investigated how meat-eaters engage with evidence strategically by examining if they avoid evidence of animals’ capacity to think and feel. We found that people who want to keep eating and enjoying meat seem to be the most likely to avoid this type of evidence.

Being strategic about meat

Many of our food choices are determined by our habits. The most reliable determinant of whether we enjoy a meal is its familiarity—that is, whether we have enjoyed it or something like it in the past. Because familiarity is such a powerful heuristic, consumer behavior is often mindless: We navigate supermarket shelves as if on auto-pilot, not concerning ourselves with thoughts of animal welfare standards or carbon footprints but with our expectations about how the food will taste.

Studies suggest that consumers rarely think about where their meat has come from when shopping. This “meat-animal dissociation” is strategic because thinking about the origins of meat can be off-putting to consumers and spoil the pleasure of a meal. When interviewed about these topics, people sometimes mention this and say they would prefer to remain ignorant because it can make purchasing meat distressing.

Avoiding evidence that animals can think and feel

In our first study, we asked about 300 meat-eaters if they engage in strategic ignorance about animals reared for food by looking at how much they agreed with statements such as: “I would rather not know about food-animals' sentience.”

We also asked them how committed they were to eating meals that contained meat, with statements like: “I don’t want to eat meals without meat.”

Those who were more committed to eating meat were more likely to want to avoid evidence about food-animals’ sentience. Ironically, this first study showed that many meat consumers—particularly those committed to eating meat—are aware that they engage in strategic ignorance.

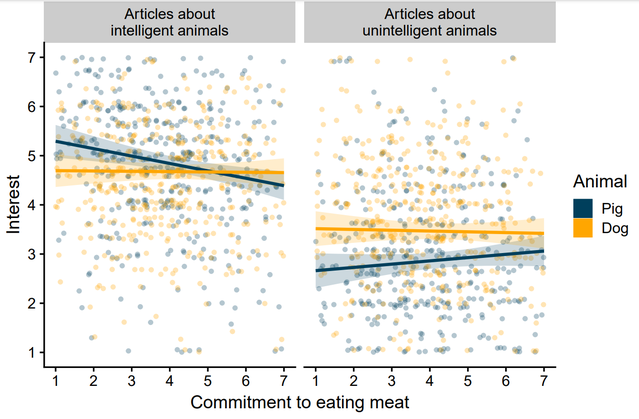

Next, we wanted to know if this avoidance applied exclusively to evidence that suggests the animals people eat are intelligent. To explore this, we asked 400 or so meat-eaters about their interest in reading scientific articles about intelligent and unintelligent pigs and dogs. We also asked them how committed they were to eating meat.

Figure 1 shows the results. Those who were more committed to eating meat were less interested in reading articles about intelligent pigs (the blue trend-line in the left panel). But they were no less interested in any of the other articles—e.g., about unintelligent pigs or dogs. This meant that a strong preference for eating meat was specifically associated with a desire to avoid evidence that makes eating animals more emotionally fraught—evidence that suggests the animals we eat are intelligent.

Figure 1

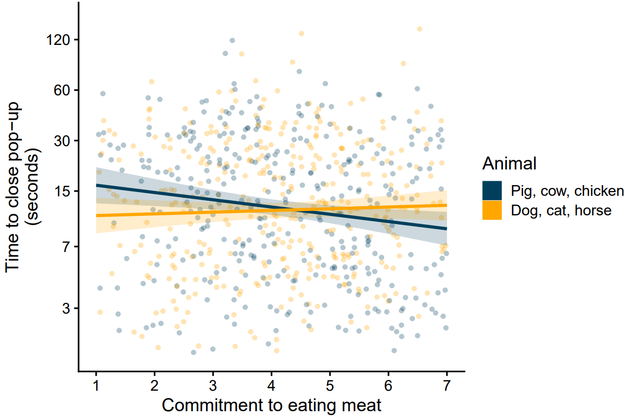

In a final set of studies, we tested what people would actually do, not just say they would do, in response to an opportunity to avoid evidence. We asked roughly 700 meat-eaters to browse a website, as they might do in their everyday lives. The website was programmed with pop-ups containing evidence documenting the intelligence of different animals, both those that are typically eaten (pigs, cows, and chickens) and those that are not (dogs, cats, and horses).

Figure 2 illustrates the results. Those who were more committed to eating meat were quicker to close the pop-ups containing evidence documenting the intelligence of pigs, cows, and chickens but were no quicker to close pop-ups with the same evidence about dogs, cats, and horses. This shows that those who are committed to eating meat really do actively avoid evidence that the animals they eat are sentient and can suffer (relative to their peers who are less committed to eating meat).

Figure 2

Confronting strategic ignorance

Our work suggests that people engage in willful ignorance as a way of neutralizing evidence that challenges meat-eating. Ignoring the fact that animals can think and feel may make it seem more acceptable to eat them. It might also help to resolve feelings of cognitive dissonance arising from believing that it is wrong to harm animals whilst simultaneously eating them.

Willful ignorance is a problem because it obscures the moral landscape. It keeps us from learning what is true and makes it needlessly difficult to determine the right course of action. Given the ethical issues arising from our treatment of animals, we need to understand how people honestly think about the facts surrounding them.

Meat-eating is the norm in most places and deciding to curtail it, for many, means foregoing a pleasurable food. The desire to keep eating meat creates the motivation for strategic ignorance, but there is reason to expect this motivation to wane in the future. More and more people are choosing vegetarian and vegan diets. An increasing number of animals are being recognized as sentient beings, and supermarket shelves are stocked with more plant-based alternatives than ever before.

As alternatives to meat become increasingly popular, we would expect openness to learning about the abilities of animals reared for food to increase in kind, with more people opting to be enlightened over remaining comfortably in the dark about animal sentience.

Jared Piazza, Ph.D., is a senior lecturer in social psychology at Lancaster University, U.K. He studies moral decision-making as it pertains to humans, food, and animals.

References

Leach, S., Piazza, J., Loughnan, S., Sutton, R. M., Kapantai, I., Dhont, K., & Douglas, K. M. (2022). Unpalatable truths: Commitment to eating meat is associated with strategic ignorance of food-animal minds. Appetite, 105935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2022.105935

Rothgerber, H., & Rosenfeld, D. L. (2021). Meat‐related cognitive dissonance: The social psychology of eating animals. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 15(5), e12592. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12592

Bastian, B., & Loughnan, S. (2017). Resolving the meat-paradox: A motivational account of morally troublesome behavior and its maintenance. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 21(3), 278-299. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868316647562