False Memories

Surprise! Fake News Spreads Fast

What we can learn from fake news.

Posted March 26, 2018

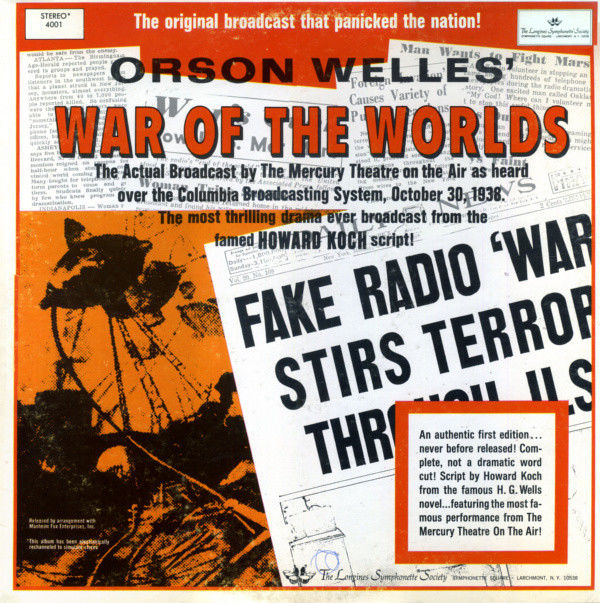

Fake news spreads faster and wider than real news, according to a recent MIT study. While this is certainly distressing news for those of us with a preference for truth, it’s also a lesson for those seeking attention and not just narcissists.

If we have any interest in persuading others, we need to grab their attention first. But each us is exposed to around 5000 commercial messages a day, a tenfold increase since 1970, and that doesn’t include other non-commercial demands on our limited bandwidth, like our email, texts, and children.

Why is fake news better at grabbing our attention? The MIT researchers found that while true news stories elicited anticipation, sadness, and joy, fake news stories created disgust and surprise. Disgust is a physical instinct that evolved to prevent us from engaging in potentially dangerous activities, such as ingesting putrid food. Surprise stops our minds in their tracks.

It’s the unexpected that grabs our attention. An old adage from journalism captures it well: “Dog bites man isn’t news; man bites dog is.”

Neuroscience teaches us that the mind is a prediction engine, unconsciously, seeking confirmation of what is expected. The unexpected stops the automatic processing keys attention, and shifts perspective.

So whether we’re just communicating information or trying to persuade, our presentation needs to be fresh, if we want people to actually listen to it. We should stay away from stock power points and stale language.

In general, though, lectures are simply not an effective way to grab and hold attention. Research has established that within five minutes, audiences stop listening, and at best listen only sparingly after. In contrast, our attention builds when we are listening to a story if it’s suspenseful.

Stories build suspense by withholding information. In the typical mystery story, a crime is committed, but we don’t know who the perpetrator is, so our attention is held by the unanswered question, “whodunnit?” Clues then tease us with potential answers.

This gives us a different and more effective way of thinking about influence. Rather than a logical presentation, we want to tell an engaging story. One approach is to start with a problem with the implicit question of how we solve it. The story then builds to the answer with tantalizing clues, just like a mystery story.

If at all possible, our solution should be positioned as unexpected. Aristotle, the first to scientifically study stories, saw the best ones as pivoting on what he called “peripeteia,” a sudden reversal of expectations that we learn from.

When we offer surprise and pique curiosity, we change minds by leveraging how the brain works. It’s far preferable to being disgusting.