Health

The Cat Piano or “The Most Singular Music You Can Imagine”

What can this odd instrument teach us about power, nature, and mental health?

Posted June 30, 2020 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

When Philip II, the king of Spain, visited Brussels in 1549, he made a grand entrance, complete with wild animals and flames. Still, by all accounts, the most impressive part of his procession was an organ that played “the most singular music you can imagine.”

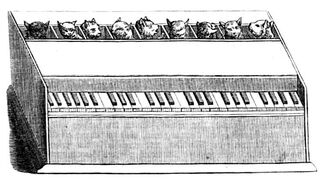

The “organ” comprised 20 narrow boxes, each containing a cat whose tail was tied to a specific key. When anyone played the instrument, the cats’ tails were pulled, “producing a lamentable meowing each time.”

This was the first documented mention of the cat piano, but it was far from the last. This torturous instrument popped up in philosophical, scientific, and psychological texts until the nineteenth century.

It would be easy to write the instrument off as “eccentric” or “odd,” but if that’s all it was, why did it crop up regularly for 300 years? If we want to get to the heart of the matter, we have to ask, what did the cat piano symbolize to people in the past, and what can it teach us about how they saw the world?

Fantasy and Power

It’s no coincidence that the cat piano made its first appearance in a royal procession. Royal spectacles were all about testing the limits of possibility. At a glance, everyone could see that the king could accomplish the unthinkable, and his power wasn’t subject to the usual restraints of money, imagination, or nature.

By parading his bear-powered cat piano through Brussels (yes, it was played by a bear), Philip II showed the world that he was undaunted by convention. He wanted people to marvel at the wonders his reign could produce. The same went for the French King Louis XI, who made his own spectacular pig organ. By making fantasy reality, kings could draw symbolically closer to God.

But what made animal-music such a potent symbol? Absurd as it may seem, the cat piano proved that these rulers had tapped into the underlying rules of nature, the Harmony of the Spheres.

The Harmony of the Spheres

The ancient concept of the Harmony of the Spheres maintained that the universe was governed by harmonic, mathematical relationships. This harmony wasn’t always audible, but for centuries, philosophers argued that certain sounds could elevate humans, bringing them closer to this divine order. Cats were a litmus test for how deep celestial harmony could go.

Cat piano creators wanted to show that these mathematical harmonies permeated all of creation. If out-of-tune meows could be synthesized into music, surely anything could. What other natural harmonies had escaped humans’ notice? Cat pianos inspired generations of music theorists, including Louis-Bertrand Castel, the inventor of the ocular harpsichord (an early color organ).

Popular Entertainment

What began as a means of accessing the divine glided easily into farcical entertainment for common people. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, cat concerts were all the rage. Take, for example, the Parisian “Concert Miaulique”: “In the middle was a monkey who kept time” while “the cats made cries or meows that were… altogether laughable.” In London in 1758, the animal trainer Samuel Bisset staged an immensely lucrative “Cats’ Opera,” and more than a century later, enthusiasts reported that cat stage companies were still all the rage.

For centuries, dogs had been prized pets in upper-class families, but cats were slow to catch on in Europe. They were often seen as transgressive and wild, suitable only for killing rats. Cruel though it was, the cat piano may have paved the way for changing perceptions of cats. Over time, it’s possible that anthropomorphic entertainments like the “Cats’ Opera” helped endear felines to a wider public.

The Cure for Melancholy

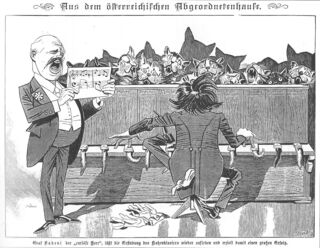

The ancient idea of “curative music” gained some traction during the early modern period, and in 1650, the German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher reported that the cat piano was an excellent cure for melancholy. He cited the example of a depressed Italian prince who couldn’t help but laugh at the cats’ frantic music.

This observation predated the discipline of psychology, but later writers took note of the cat piano’s therapeutic potential. One of the nineteenth-century founders of psychiatry, Christian Reil (1753-1813), argued that the cat piano could help patients who were lost in constant reverie. Daydreamers, he argued, had trouble paying attention to objects in the real world, but the bizarre, jarring nature of the cat piano could jolt them back to reality.

According to Reil, mental illness was an affliction of the nervous system, and all psychological problems could be traced back to the malfunctioning of the brain and nerves. Sensory jolts, like the cat piano, brought the mind back to itself. They held a vital key to mental health.

Unravel Alien Systems of Meaning

It’s a well-known idiom that “the past is a foreign country,” but all too often, we act as if the past is self-evident. The cat piano shows that simply isn’t true.

The historian Robert Darnton is a master of using seemingly “weird” events to understand the past in a deeper, richer way. Any time you realize you aren’t “getting” something, he suggests, that’s your cue to dig deeper and “unravel an alien system of meaning.”

The cat piano wasn’t just a bizarre or frivolous instrument. To its advocates, it was a means of accessing truth, power, and well-being. But we can only see that when we check our initial biases and seek to truly understand former ways of thinking.

That doesn’t mean we have to condone past actions, but it does indicate that we must take time to unravel their meanings before we can form a fair assessment. Empathy is an essential part of good judgment.

A Postscript on Cruelty

I’d be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge the cat piano’s cruelty. Historians have debated whether the cat piano really existed, but widespread cruelty toward cats was common in early modern Europe. Darnton explains some of the complex reasons why people condoned cat cruelty. For example, cats were frequently associated with the devil and loose morals.

References

Bomare, Jacques Christophe Valmont de. Dictionnaire raisonné universel d’histoire naturelle. Paris: Lacombe, 1768, s.v. “chat,” 2:50-51.

Darnton, Robert. The Great Cat Massacre and Other Episodes in French Cultural History. New York: Basic Books, 1984.

Kircher, Athanasius. Musurgia universalis. Rome: Francesco Corbelletti, 1650, 1:37.

Richards, Robert J. “Rhapsodies on a Cat-Piano, or Johann Christian Reil and the Foundations of Romantic Psychiatry.” Critical Inquiry 24, no. 3 (Spring 1998): 700-736.

Weckerlin, J.-B. Musiciana. Paris: Garnier Frères, 1877.

Weir, Harrison. Our Cats and All About Them: Their Varieties, Habits, and Management; and for Show, the Standard of Excellence and Beauty. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin, and Co., 1889.