Suicide

Suicide as Sickness?

When we medicalize suicide, do we do more harm than good?

Posted June 13, 2018

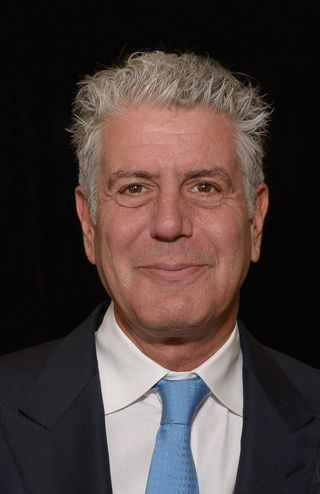

The heartrending suicides of Kate Spade and Anthony Bourdain shocked and upset us. Here were two eminently successful people who ended their own lives. Why would they do this? How could they have achieved so much, yet not want to keep living? Their suicides struck most of us as not only tragic, but bewildering.

In the aftermath of these two highly publicized deaths, a much-needed debate has ensued about suicide—its causes and its prevention. Some have argued that suicide is the product of mental disorder. This encapsulates the illness model of suicide, which maintains that people who kill themselves are mentally ill. Because they are sick, we must medically treat them if we are to restore them to mental health. In keeping with this view, illness model advocates contend that suicide is a byproduct of mood, anxiety, and other mental disorders. However, in some instances, illness model advocates go even further, arguing that suicidal behavior itself constitutes a disorder. For example, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) includes a proposed (but still unofficial) disorder called suicidal behavior disorder. Anybody who has attempted suicide in the past two years for non-political or non-religious purposes qualifies for this disorder, according to the draft criteria. Seeing suicidal behavior as disordered is consistent with the illness model. The implication is that reducing suicide requires curing the underlying mental disorders of those who attempt it.

This sounds good, but there is reason to pause before wholeheartedly endorsing the illness model. A press release from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) issued the same week as Spade and Bourdain’s suicides points out that over half of people who die by suicide have no diagnosable mental disorder. However, a variety of (often overlooked) social factors are consistently correlated with suicide—things like relationship problems, grief and loss, substance use issues, ongoing physical health difficulties, and stressors related to employment, housing, and the law. Thus, the CDC press release draws attention to the sociocultural model of suicide, which attributes suicidal behavior to unbearable social, economic, and cultural circumstances. Rather than seeing people who resort to suicide as sick, the sociocultural model sees suicide as a response to oppressive social conditions. If the CDC data is to be believed, we may be exaggerating the role of individual defects in suicide, while overlooking the powerful impact of sociocultural circumstances.

I am not trying to set up an either/or divide here. Clearly, self-harming behavior emerges from a complex interplay of individual and social factors. However, when we privilege the former and pin suicide primarily on mental illness, we espouse a position that suggests that the solution is to adapt people to existing social conditions rather than to reflectively examine (and change) such conditions. The CDC press release points to an especially alarming statistic, namely that suicide is up more than 30% in over half of U.S. states since 1999. Is the best explanation for this horrifying trend simply that more people are mentally ill? Or might we look to other factors—such as loneliness in a culture that values individual accomplishment over connectedness and relationships, fraying community ties, heightened political alienation in our increasingly partisan “Red-Blue” divide, socioeconomic stressors as the rich get richer and the rest of us struggle to make ends meet, and growing isolation as people interact less and spend more time online?

The problem with psychology (and the psychologizing discourse it encourages) is that it tends to reduce everything to an individual problem inside the person. But psychology often forgets to look at broader sociocultural explanations for human unhappiness. As one notable (and timely) example, economists Anne Case and Angus Deacon found that death rates for middle-aged white Americans have been steadily increasing since 1999. They attribute this alarming increase to “lack of steady, well-paying jobs for whites without college degrees,” which they believe “has caused pain, distress and social dysfunction to build up over time.” The result is a spike in “deaths of despair”—suicides and other self-harming behaviors that result in death. Of course, Kate Spade and Anthony Bourdain were not faced with economic problems tied to low paying jobs. To the rest of us, they appeared to “have it all.” However, wealth and fame offer no guarantees; they cannot fully shield people from the vast array of sociocultural factors associated with suicide (e.g., loneliness, grief and loss, work-related stress, relationship conflicts, physical illness, and social isolation).

Attributing suicide mainly to mental illnesses inside individuals discourages the examination of broader social conditions. This is not to say that mental health services aren’t crucial. When we provide self-help hotlines, psychotherapy, and other suicide-prevention programs to those who have sunk so low into misery and despair that they are uncertain whether they wish to keep living, we are indeed offering the kinds of social connectedness that suicidal individuals often sorely lack. Yet do we not run the risk of making suicide prevention too much of an individual problem when we primarily speak about it as a product of sick minds rather impoverished societal values and untenable social conditions? As suicide rates continue to spike, this is a question that urgently requires consideration.

IF YOU OR SOMEONE YOU KNOW IS IN CRISIS OR IN NEED OF IMMEDIATE HELP, CALL 1-800-273-TALK (8255). This is a free hotline available 24 hours a day to anyone experiencing emotional distress or a suicidal crisis.