Relationships

Love and Self-Transcendence

Pursuing self-actualization without love may lead to destructive ambition.

Posted April 25, 2024 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Have you ever encountered someone whose very presence makes you want to be a better person? Meet Tanya, a living embodiment of what Abraham Maslow termed "self-transcendence"—a state beyond self-actualization. Unlike the flashy influencers we're bombarded with daily, Tanya moves quietly through the world. Her kindness fosters community, and her humility teaches by example.

What is the recipe for being like Tanya? We turn to recent findings in psychology and neuroscience to uncover a few patterns.

What Is Self-Transcendence?

Imagine climbing a mountain, not to plant your flag at the top, but to see the world beyond and understand your place within it. This is the essence of self-transcendence. It goes a step beyond achieving personal goals; it's about contributing to the greater good, stepping outside yourself, and connecting to something bigger.

People like Tanya see beyond their own needs and desires and show us that happiness is not what we take but what we give. Unlike self-actualized individuals, transcenders use all aspects of themselves for the collective good, driven by a deep ethical commitment to humanity.

The Psychology of Self-Transcendence as a State vs Trait

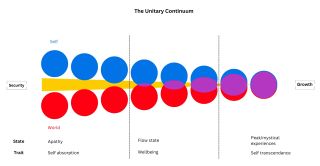

To explore the psychology behind self-transcendence, refer to Figure 1. This model demonstrates that self-transcendence is the result of feeling less separate from the world socially and spatially, as you can see towards the right where self and world merge and eventually become one. "The Unitary Continuum" was introduced by David Yaden, referring to states that are brief self-transcendent moments ranging in intensity from mindfulness, flow, awe, peak, to mystical experiences. These moments are said to be blissful, insightful, and indescribable. I extended Yaden’s original model by connecting it to self-transcendence as a 'trait', a stable disposition, based on Abraham Maslow's observations that self-transcendent individuals frequently report such experiences. In reference to Figure 1, a self-absorbed disposition is one where the individual feels separate from others and the world, while self-transcendent individuals may feel an above average connection and thus have frequent self-transcendent experiences (peak/mystical).

Skully and the Hero Complex

At the opposite end of the self-transcendence continuum, we have Skully, mostly operating from the left end of it. In contrast to Tanya’s altruistic drive, Skully's motivations are rooted in personal recognition; the bookends of the spectrum showcase motivations at opposite ends of the continuum.

Motivations: B-love Versus D-love

The journey toward self-transcendence is marked by the motivations of our love: B-love (being-love) is about giving without expecting in return, similar to agape or altruism, while D-love (deficiency-love) is about taking to fill a void. These terms were coined by Abraham Maslow and are referred to here for clarity. Certain historical figures embody these opposites—Hitler's destructive ambition vs. Mother Teresa's commitment to humanitarian work—demonstrating outcomes guided by our intentions. The distinction is further analyzed through psychological measures like the Light and Dark Triad scales.

Light Versus Dark Triad

The dark triad scale was developed in 2002 by Delroy L. Paulhus and Kevin M. Williams, while the light triad was developed recently in 2019 by Scott Barry Kaufman, David Yaden, Elizabeth Hyde, and Eli Tsukayama. The more one moves right on the continuum, the more they exhibit traits associated with the light triad. Conversely, as feelings of isolation from the world intensify, traits linked to the dark triad begin to surface. Interestingly, a comprehensive study in 2019 conducted by Kaufman and others titled "The Light vs. Dark Triad of Personality: Contrasting Two Very Different Profiles of Human Nature" indicates that the Light Triad reveals a modest positive correlation with self-transcendence, well-being, and agape (selfless love), among other positive associations.

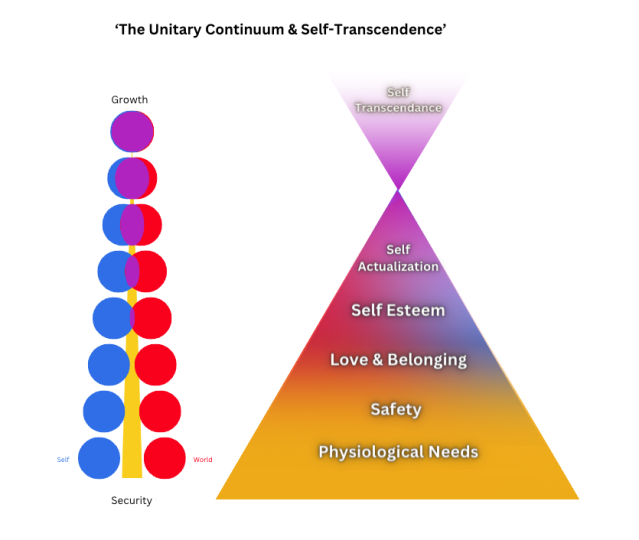

Light Triad: What Underlies B-Love—Met Needs

B-love (being-love) is based on selflessly giving without expecting anything in return, seen in people like Tanya who had nurturing upbringings where their basic needs for safety, belonging, and esteem were met. This results in them living from a place of abundance, allowing them to generously offer love and support. Tanya's positive life circumstances, including a stable family, strong friendships, and supportive community, have enhanced her ability to love freely, reflecting the fulfillment of Maslow's hierarchy of needs, particularly belonging and esteem. This enables her to express love outwardly (see figure 2 which is a visual representation of the famous hierarchy of needs).

Dark Triad: What Underlies D-love—Unmet Needs

On the other hand, Skully has a proclivity towards seeking recognition through social media. He’ll take advantage of people in an obsessive pursuit of success. Looking deeper, we see Skully is unconsciously compensating for an internal void. He experienced trauma as a socioeconomically disadvantaged child with a learning disability. This led to him being bullied and feeling ostracized, leaving an emotional wound that halted his growth through the belonging and self-esteem stages. Consequently, Skully exhibits prominent Dark Triad traits, rooted in a feeling of disconnection, and finds himself on the left end of the unitary continuum.

This highlights significant separation from others. Addressing his unmet needs and emotional wounds can help him shift towards the right end of the continuum, thus enhancing both his personal well-being and positive impact on others. Overall, self-transcendence is good for Skully and for the world around him.

The Neuroscience of Self-Transcendence

Moving from D-love to B-love, Dark Triad to Light Triad, physiological needs to self-transcendence, and overall left to right on the unitary continuum is not just all in your head—well, technically, it is, but there's science behind it. Studies by David B. Yaden and Andrew Newberg in neurotheology show that moving into a state of self-transcendent experience quiets the parts of the brain focused on the self. Their research, detailed in The Varieties of Spiritual Experiences (2022), indicates that one of the changes in the brain during self-transcendent experiences is the deactivation of the default mode network (DMN) which is responsible for linear self-referential thinking.

As the DMN turns off, the new connections increase. These emerging connections are what underlie creative states like flow, where parietal self-transcendent experiences may occur. Essentially, by letting go of our conditioned sense of "self", our brain opens up to new connections and potentially self-transcendent experiences. These self-transcendent experiences are thought to underlie positive behavior change (Yaden et al., 2022, p.59).

Our True Essence: Selfless Love (Agape)

By setting aside personal desires, self-transcenders find fulfillment in serving something beyond themselves—be it nurturing healthy children, advancing research, or enhancing human lives through technology. This principle underlies a paradox at the heart of human experience: Our search for love is fulfilled not in receiving it, but in giving it, as highlighted by the psychologist Erich Fromm.

Perhaps this is why positive psychology interventions such as loving-kindness meditation, gift of time, and gratitude letters work to improve well-being. These interventions appear to increase B-love, and at our core, we yearn to connect, to love, and to be loved. This truth is echoed by many thinkers, including Mary Cosimano from John Hopkins University, who wrote a paper in 2014 titled "Love: The Nature of Our True Self" in which she says that love is connection. Dr. Brene Brown shares the same understanding, saying, “Love is the greatest thing we do. It is the reason we’re here. We’re here to love.”

Conclusion

Our path forward is clear: To self-transcend, to truly make a difference, we must choose love—love that is holistic, generous, connective, and elevates not only ourselves but also those around us. In doing so, we may not only find our true passions but also contribute to a world in dire need of such light. In saying that, it’s also pertinent to mention that residing in either of the extremes of the unitary continuum is not practical and that we should strive to land in the middle, at well-being.

References

Cosimano, M. (2014). Love: The nature of our true self. MAPS Bulletin Annual Report, Winter 2014, 39-41.

Fromm, E. (1956). The art of loving. Harper & Row.

Kaufman, S. B., Yaden, D. B., Hyde, E., & Tsukayama, E. (2019). The Light vs. Dark Triad of Personality: Contrasting two very different profiles of human nature. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 467. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00467

Newberg, A. B., & d’Aquili, E. G. (2000). The neuropsychology of religious and spiritual experience. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 7, 11–12.

Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The Dark Triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36(6), 556-563. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6

Yaden, D. B., & Newberg, A. (2022). The varieties of spiritual experience 21st century research and perspectives. Oxford University Press.

Yaden, D. B., Haidt, J., Hood, R. W., Vago, D. R., & Newberg, A. B. (2017). The Varieties of Self-Transcendent Experience. Review of General Psychology, 21(2), 143–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000102