Sex

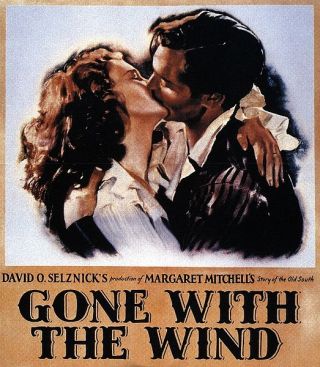

Gone with the Wind and Xica: Two Myths of Slavery

Brazil and the U.S. romanticized slavery in film in very different ways.

Posted March 3, 2015

It has been 75 years since Gone with the Wind was released early in 1940 and became a blockbuster hit. The film’s release took place nearly two years before Pearl Harbor and the U.S’ entry into World War II, a time when segregation was the law and lynchings were common in the South and when blatant racial discrimination existed throughout the U.S.

Slaves were shown in the film as unintelligent and childlike, content with their lot, with only some deviants choosing to seek freedom. An earlier film classic, D. W. Griffith’s 1915 Birth of a Nation portrayed African-American men as sexual predators, lusting for white women. Neither film depicted the brutality of slavery and of the de jure and de facto segregation that followed.

The stereotypes of African-Americans in the two films, with variations over the years, are familiar to Americans—unintelligent and either passively acquiescent or menacingly dangerous. Many Americans still believe in some version of the following false reasoning: Skin color, intelligence, and personality are inherited; therefore black inferiority is biologically based. (This and other issues of biology and culture are discussed in detail in my book The Myth of Race.)

Slavery in Brazil was at least as brutal as in the U.S., was more widespread (several times as great a percentage of Brazilians were African slaves as the percentage of Americans) and ended later (1888, as compared to 1865 in the U.S.).

Brazilians also have their myths about slavery and about race, but they are very different from ours. Consider, for example, the 1976 Brazilian film Xica (pronounced SHEE-ka; Brazilian title Xica da Silva.)

Here is how Wikipedia describes the film’s plot:

"The film is based on the novel Memórias do Distrito de Diamantina, written by João Felicio dos Santos (who has a small role in the film as a Roman Catholic pastor). It is a romanticized retelling of the true story of Chica da Silva, an 18th-century African slave in the state of Minas Gerais, who attracts the attention of João Fernandes de Oliveira, a Portuguese sent by Lisbon with the Crown's exclusive contract for mining diamonds, and eventually becomes his lover. He quickly asserts control, letting the intendant and other authorities know that he's onto their corruption scheme. Eventually Lisbon hears of João's excesses and sends an inspector. José, a political radical, provides Xica refuge."

Interestingly, the Wikipedia summary, presumably written by Americans with no special knowledge of Brazil, says little about the film’s main character.

In contrast, Randal Johnson, a Brazil scholar and professor of Portuguese, wrote a review of the film. Here is how he characterizes Xica and her power:

"Xica is portrayed throughout as having certain unrevealed sexual abilities which make her unique in the region. Her rise to power is based precisely on her sexual prowess, which reveals a dismaying sexist and racist approach to the problems of black women in Brazilian society...

[Much] of the film deals with Xica's rise to power, her vindictiveness and extravagance while in power and her subsequent fall from power. She is seen as an object of the desire of the most important men in the village, including the Intendent (the holder of civilian power) and, finally, the Contractor himself. She first attracts Joao Fernandes' attention, which leads to his purchase of her from the Master Sargeant, through the premeditated exposure of her body as the Contractor is meeting with the Intendent and the Master Sargeant.

Soon after buying Xica, Joao Fernandes' other slaves comment wryly that he has become her slave sexually."

To put it mildly, the racial stereotypes personified by Xica have nothing in common with those in Gone with the Wind, and are alien to American sensibilities.

The American film is a love story about whites, with slavery as a backdrop, while the Brazilian film is a comedy about interracial sex during slavery. And instead of portraying sex between a male master and his female slave as rape, Xica depicts the slave as using her feminine wiles to dominate the master and achieve political power.

All cultures are ethnocentric, and ours is no different. Too often, we Americans view race relations in other countries through the prism of our own experience: slavery leads to inequality—end of story. In doing so, we fail to understand the everyday texture of life in another culture, with its different categories of race, gender, and social class, and with its different forms of interpersonal relations, including sexual relationships.

Furthermore, if racial differences in behavior were based in biology, then racial stereotypes in different cultures would be recognizably similar to one another. But, as the two films illustrate, we do not see this similarity. While American and Brazilian racial stereotypes may serve a similar function in providing justifications for the inequitable treatment of the descendants of slaves, their very different content is evidence that the stereotypes have their origins in culture, not in biology.

Check out my most recent book, The Myth of Race, which debunks common misconceptions, as well as my other books.

The Myth of Race is available on Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Friend/Like me on Facebook.

Follow me on Twitter.

Visit my website.