Relationships

The Pyramid of Perspectives

Is love in my hormones, my heart, or my head?

Posted December 2, 2020 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

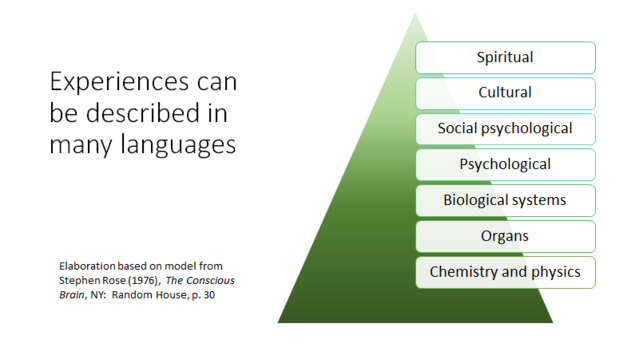

A long time ago, a graphic offered by Steven Rose in his 1976 book, The Conscious Brain, inspired one of my professors to suggest that Rose’s pyramid for explaining consciousness (page 30) could be modified to label the perspectives from which we describe our personal experiences. Ever since, I have pondered this schema, asked myself what language I or someone else is using to reflect upon their own reactions to internal or external happenings, and modified his visual to fit the data I saw in my clinical office and research literature. My diagram above shows that we can talk about — or study — the same human phenomenon using at least seven different languages, giving rise to at least seven separate perspectives.

I illustrated the value of this approach in Benefits of Sex After 50 and reflected on its utility in a follow-up, Yes, Older Adults Do Enjoy Sex. I revisited the model most recently in Six Ways the Wisdom of Your Body Can Enhance Intimacy. In my recent post about the benefits of breathing and yoga, I realized how much I appreciate the discipline of yoga from all seven perspectives. As these essays show, a journey through the languages and the kind of research they inspire can make the language pyramid come to life and demonstrate its usefulness.

After a long day of concentration and effort, you might say “the neurons in my brain feel fried” (chemistry and physics) as well as “my brain won’t work anymore” (organ) or “my nervous system refuses to keep processing” (biological system) or “I can’t think any additional thoughts” (psychological) or “Sorry, but I’m not taking in what you are saying” (social-psychological) or “I know this ad is telling me something but I can no longer process what it is saying” (cultural) or even cry out, “Help me, Universe! I am not grasping the meaning of the messages you are sending me!” (spiritual). Today, let’s dive into a bit more detail:

Physics and Chemistry. At the most basic level, we are an ever-changing, ever-evolving collection of cells and the processes that affect them. The plumbing and wiring in the human body are the elementary parameters of our experience. The exploding areas of neuroscience and the technologies that can measure our cellular structures and movements capture this level of experience eloquently. They can document invisible stamps on essential matter and demonstrate that we respond to stimuli of which we may or may not be aware, as shown by John Bargh and his colleagues.

Organs. People’s reactions manifest in various organs of their body, sometimes in an idiosyncratic fashion. Nonetheless, research has shown the heart is associated with arousal, loss, and compassion, the stomach with hunger or overindulgence in consumption, clammy skin with anxiety, muscle tension with goal pursuit. When I feel fear, my lungs tighten and my breathing shifts, foreshadowing the next level of discourse.

Biological Systems. Whole systems in our body come into play as we respond to internal or external stimuli. The threat of an invasive organism (viral or bacterial, for example, or even air or noise pollution), can activate a whole response system: the digestive system can become disrupted, our skin can break out, respiration can increase or decrease, bringing shifts in blood pressure along with it.

Psychology. How do we describe what is happening to us at a psychological level? What are we perceiving, thinking, feeling? What impulses for action (that is, motivation to respond) are we aware of? How are we behaving and how do we understand our behavior? Do we see it as intentional, crafted through conscious choices, or unconscious, taking place without engagement of our awareness? Do we perceive the triggers as coming from inside or outside of our own bodies? (See the work of Princeton’s Diana Tamir, whose research takes us across the bridge to the next level.)

Social-Psychological. Even when we are alone, we are always experiencing ourselves as part of an interpersonal field. From our earliest age, we have internalized “scripts” of how the world (especially the human world) works. These sets of unconscious expectations can be brought into consciousness and amended or revised, most obviously through therapy or education, or interpersonal conversations that sensitize us to the impact we have on others and their effect on us. Consider the way that an external experience (such as a political event, a high decibel level, the smell of garlic and onions or cinnamon and apples) impacts us, compared to how it affects someone else. In this way, we become aware of when and how our responses may be universal, common to a cultural group, or unique.

Cultural. Any experience is filtered through the lenses of the culture(s) that we have known and to which we are exposed at the present moment. As basic an act as eating a meal takes on a different meaning depending on the culture in which it is experienced. In France, the act of eating is meant to be about far more than nutrition or hunger. From the earliest ages, schoolchildren are trained through government-sponsored lunch programs to see meals as opportunities to learn, share, discriminate, and above all experience pleasure. Just watch this video. Is your breakfast experience about feeding your cells? Filling an empty stomach or nourishing your brain? Fueling your digestive system? Providing sensory stimulation and perhaps pleasure? Offering an opportunity to share early moments during your day or to savor solitude before relating to others? A chance to engage in a cultural ritual, perhaps coffee from a favorite shop or barista? Or sacred moments with which you begin your day?

Spiritual. Many people believe in a transcendent level of being, one in which nonmaterial reality is the greatest truth, enveloping all others. Many religious perspectives, especially those grounded in mysticism, share at least a semi-transcendent and sometimes a radical transcendent assessment of reality. These world-views, which contrast dramatically with materialism, are documented brilliantly by the Canadian psychologist, Imants Baruss. He has shown (reference below) that these world-views not only exist in empirical reality but are each subscribed to by substantial numbers of people. Any phenomenon can be reconstrued as conveying an abstract message or even a mystical meaning.

Now that the pyramid of perspectives Is explained, why might it be useful? Here are three major applications.

- Further understanding. Setting an experience in a particular language, examining research and data relating to that level can further our understanding of that experience.

- Guiding intervention. If the problem is seen as one of hormones or neurotransmitters, then pharmaceuticals (more chemicals) might be called for; if the problem is seen as a muscle sitting on a nerve, then a structural repair (surgery, massage) might be chosen. At a biological systems level, perhaps acupuncture or yogic realignment might be tried. In a psychological approach, thoughts or emotions, or behaviors associated with the pain might be examined. At the social-psychological level, relationship triggers and remedies would be sought, using learning techniques to change a behavior. The triggers in the media messages or expectations could be identified on the cultural level; prayers or chants or hymns or a search for meaning might signal a spiritual assessment of the situation and ways to respond to it.

- Offering alternative ways of thinking about the situation. When we can move between and among the different levels of analysis, our resources expand accordingly. Is love about dopamine and oxytocin, or better grasped as attachment, passion, caring? Maybe another sense is even more useful. The theologian Paul Tillich saw it as “the ground of being." Perhaps love is the ground all along, rather than the figure, and we do not “fall into” love as much as we can remove protective, although often necessary, barriers to loving.

Then again, perhaps we love across all seven levels of language.

Copyright 2020 Roni Beth Tower

References

Baruss, I. (1990). The Personal Nature of Notions of Consciousness: A Theoretical and Empirical Examination of the Role of the Person in the Understanding of Consciousness. New York and London: Lanham.

Rose, S. (1976). The Conscious Brain. New York: Vintage Books.