Motherhood has been the subject of scholarly and creative writing for centuries. There is much written on the demands, the exhilaration, the drama, and the formidable task of adjusting to the onslaught of challenges. Along with the joys that accompany the transition to this major event in a woman’s life, motherhood may also be a stressful experience that generates intense anxiety and pervasive feelings of incompetence and loneliness.

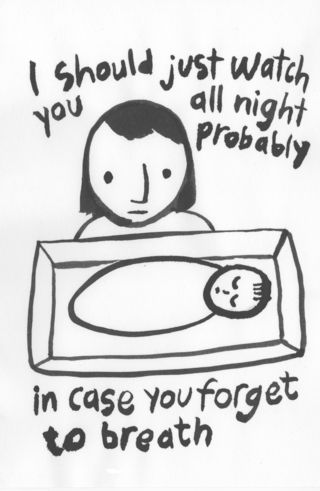

Still, only recently have mothers, researchers, and clinicians come forward to address the alarming nature of maternal musings. Unsettling and unwanted thoughts can emerge on a continuum of tolerance, with some experienced as a nuisance, whereas others torment a mother’s mind until she believes she is most certainly going mad. When this happens, the associated distress and scary thoughts permeate the very air she breathes.

There are two important points to be made. Understanding anxiety within the context of motherhood can evoke both controversy and earnest sentiment. Many renowned writers have made the case for more stringent societal acceptance of the rampant anxiety and demands of motherhood. One even went so far as to label it a perfect madness (Warner, 2005). As Judith Warner states in her book with this title, “[This book] is an explanation of a feeling. That caught-by-the-throat feeling that so many mothers have today that they are always doing something wrong. And it’s about this conviction I have that this feeling—this widespread, choking cocktail of guilt and anxiety and resentment and regret—is poisoning motherhood for American women today” (Warner, 2005, p. 4). Warner holds numerous factions accountable for this current generation of mothers under pressure, from media-soaked promises of absolute excellence to feministic declarations of grand achievements. The claim that mothers are sentenced to this state of chronic discontent paints a bleak picture, to be sure. Furthermore, if mothers are already feeling condemned to standards of perfection by society, by their friends, family and by themselves, how can they ever be expected to free themselves from the “existential anxiety” that ubiquitously controls their every move? Not a comforting thought.

Adding to this frenzy is a second consideration, the concept of trait anxiety. This concept refers to the intrinsic tendency to react with anxiety across a number of situations and different times throughout a person’s life. Jerome Kagan, a Harvard professor of psychology, spent years researching the way in which a baby’s innate temperament impacts a person’s development over time (Kagan & Snidman, 2009). He discovered that babies who are highly reactive tend to grow up anxious and concluded that some people are predisposed to this highly reactive state and are, quite simply, born anxious. A recent New York Times review of Kagan’s somewhat controversial work highlighted the point that “some people, no matter how robust their stock portfolios or how healthy their children, are always mentally preparing for doom. They are just born worriers, their brains forever anticipating the dropping of some dreaded other shoe” (Henig, 2009, para. 8). When we consider the implications of trait anxiety in postpartum women, we find women who are consistently putting forth their best efforts, who, at the same time, think they are never doing quite enough. Some women are born anxious. Some babies have highly reactive temperaments.

Ultimately, a mother can only do her best.

Of course, there are experts who might argue that this notion of trait anxiety is in direct conflict with the assertion of developmental psychologists—that each of us is born with a blank slate, and environmental influences reign supreme. For instance, the philosophy of attachment parenting promotes the belief that emotional sensitivity and physical closeness is the underlying principle behind developmental health: stay in close contact to your baby, breastfeed with skin-to-skin contact, and wear the baby with you so he can hear your heartbeat. Although no one disputes the power of the mother-child bond and its impact on future development, Kagan claims that a child’s temperament, which is inherited and potentially linked to certain sets of emotions and behaviors, can only be slightly influenced by the parents (Kagan & Snidman 2009). This is the precise point that makes his theory divisive.

The debate of nature versus nurture is not new. The relevance here is that, depending on one’s frame of reference, mothers could, conceivably, be taking on way too much responsibility for things that may be largely out of their control. Consider the mother who has made a secure attachment with her baby who possesses a high-reactive temperament. This child may be challenging and difficult to soothe, prompting the mother to assume unjust blame. Interestingly, the message here is twofold: Mothers should not undeservedly blame themselves for the disposition of their baby, nor should they blame themselves for their own heightened degree of anxiety which may, or may not, be an intrinsic tendency.

If we combine the perfect madness (Warner, 2004) of the enduring societal pressure cooker with the notion of inherited predispositions of some women to be more anxious than others, we find a volatile condition looming in the shadows. We, as a society and as individuals, need to recalibrate expectations in order to alleviate the continuous and unnecessary self-blame, guilt, and liability, which mothers assume for things that are beyond their control. Motherhood is a period in one’s life that is fraught with unpredictability and crushing uncertainties. It seems that no matter how hard they try or how quickly they move, mothers cannot outrun their cascading worries and scary thoughts.Yet, armed with information and support, mothers can indeed distract themselves from the temptation to surrender to the forces that hold them back from experiencing joy and find the tools to help them do so.

Adapted from "Dropping the Baby and Other Scary Thoughts" by Karen Kleiman and Amy Wenzel (Routledge, 2011)