Law and Crime

The United States of Surveillance

Has surveillance been normalized in the United States?

Posted March 8, 2022 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

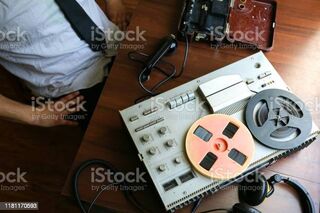

This post is a review of The Listeners: A History of Wiretapping in the United States. By Brian Hochman. Harvard University Press. 360 pp. $35.

Writing for a 5-4 majority in Olmstead v. The United States (1928), Chief Justice William Howard Taft upheld the right of the government to wiretap Roy Olmstead, “King of the Bootleggers.” The Fourth Amendment “does not forbid what was done here,” Taft declared. “There was no searching. There was no seizure. The evidence was secured by the sense of hearing, and that only.”

In his dissent, Justice Louis Brandeis maintained that wiretapping violated a citizen’s “right to be let alone – the most comprehensive of rights and the right most favored by civilized.” In the future, Brandeis warned, the government would acquire “subtler and more far-reaching means of invading privacy.” In his own dissent, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes blasted wiretapping as “a dirty business.”

Olmstead v. The United States, Brian Hochman, the director of American Studies at Georgetown University, reveals, was part of a passionate and protracted debate over the appropriate use of wiretapping in America. In The Listeners, Hochman examines that debate from the birth of wiretapping during the Civil War to 2001, when the attack on the World Trade Center ushered in a new age of electronic surveillance. Hochman makes a compelling case that concerns about threats to privacy that had been widely shared by Americans were pushed to the margins by claims that eavesdropping was necessary to enforce Prohibition, defeat drug dealers, prevent race riots, and protect national security.

The Listeners provides an engaging and informative account of wiretapping in American popular culture. Hochman examines the impact of The Eavesdroppers, Samuel Dash’s landmark 1959 study; the myth of the bugged martini olive; Francis Ford Coppola’s movie, The Conversation; and the much-acclaimed HBO series, The Wire. And he assesses the implications for surveillance and privacy of the transformation from analog to digital technology.

Hochman also analyzes 20th-century legislation and judicial decisions that have permitted private businesses, law enforcement officials, and government agencies to surveil American citizens. In Section 605 of the Federal Communications Act of 1934, he points out, Congress appeared to make intercepting and divulging private communications a federal crime. In a series of decisions, the Supreme Court sustained that interpretation. However, in 1940, President Roosevelt issued a secret memorandum in which he provided a national defense exception to government wiretapping in light of the threat of sabotage and espionage.

In a “paradox that has mostly escaped public notice,” Hochman writes, as the Supreme Court laid the constitutional foundations for the right to privacy in the 1960s and '70s, Congress and the courts “enshrined government eavesdropping into law.” Responding to urban riots and a surge in crime, Congress scrapped a proposed Right of Privacy Act. When the Supreme Court overturned Olmstead, the justices identified the conditions under which eavesdropping was permissible, laying the groundwork for the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (under which judges rubber-stamped almost every wiretap application). And, although the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act set strict limits on the duration and scope of wiretapping, it authorized the practice for a “shopping list” of major crimes and allowed police to tap and bug without warrants for 40 hours in “emergency situations.”

According to Hochman, except for government wiretapping for national security, “public acceptance has stayed more or less constant since the early 1970s.” Eavesdropping is no longer “a dirty business.”

The Listeners ends with the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. The USA Patriot Act, Hochman emphasizes, enabled the National Security Agency “to launch data-mining operations of enormous complexity and scale.” Equally ominous, the emergence of social media platforms, search engines, apps, cookies and smartphones has marked the arrival of “surveillance capitalism,” in “which economic growth and everyday life depend on the ability to monetize the private information we freely surrender in the service of connectivity.”

“Our voices and conversations,” Hochman concludes, gloomily and perhaps a bit hyperbolically, “are largely incidental” to the NSA and Google… As individual selves, our significance has largely vanished.”