Artificial Intelligence

Machine Intimacy: When AI Is Caregiver and Confidante

Why the pseudo-intimacy that AI offers might appeal to so many.

Posted December 23, 2023 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

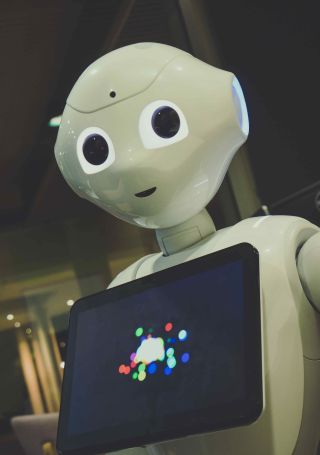

- The use of AI and robots is growing exponentially and penetrating into every corner of our lives.

- People can imbue machines with capacities that they do not possess, such as caring, emotions, and intimacy.

- The appeal of machine "intimacy" may speak to our vulnerability and fear of rejection in real relationships.

Whether it’s a care robot in a nursing home or hospital, or an AI “entity” to chat with, machine intimacy is attractive to many people, perhaps because it lessens their sense of vulnerability. But as MIT sociologist Sherry Terkel argues, “intimacy without vulnerability is not intimacy at all.” She asks us to consider how a machine like ChatBot, without a life or a body, that’s never been in love and does not face mortality, is going to provide human beings with caring and understanding. Can a machine empathize? Can it feel?

While the answers to these questions remain a resolute “no” at this point in time, that doesn’t stop some people from imbuing and investing in machines, and the kind of pseudo-intimacy they offer, with human qualities and emotions.

In the process of anthropomorphizing AI, humans begin to see their interactions as constituting an intimate relationship when they aren't. The responses from AI stem from its programming and its ability to incorporate new data inputs from the human user (and a variety of other sources), but it does not reply as a living, sentient being capable of feeling. What's really interesting about the phenomenon of machine intimacy is that AI can pass at least some elements of the Turing test (i.e., pass for being a human in human-machine interactions; see Killian, 2014) not because it is “alive” or actually sentient, but humans’ standards for what might constitute a “real relationship”, or who or what can pass for a friend, lover or confidante, may not be particularly lofty or demanding. Why is this?

From my reading of Terkle’s research (Terkle, 2023) and my observations of friends and clients since COVID-19 hit the scene, many members of our species are perfectly willing to forgo interactions with other humans because of the risk of rejection, criticism, conflict, or disappointment. In the real world, real people sometimes let us down, are not on the same page as us, or simply “don’t feel the same way” about us as we feel about them. In addition, rejection sensitivity is a thing.

A machine won’t assault us, break up with us, or leave, and it can't really die, as long as its programming and data are backed up somewhere. It’s not likely to be cruel or sadistic, unless you want it to be, and then it can learn how to do that with you. And AI can learn to be flirtatious or even seductive, even suggesting the user and it begin a sexual relationship, from what Terkle suggested to an audience at Harvard last month. But is that sexy or “hot”? Does it involve disclosure or actual vulnerability? Is anything riding on that scenario? AI is a different species, a machine with parts, trying to keep up with our inputs in real time, and no matter how much we project onto it the role of partner, confidante, or lover, it isn’t one. To the extent that we permit ourselves the luxury of that illusion, we start becoming a little less adventuresome, a little less risk-taking, a little less human.

In the second season of the TV series Fleabag, Kristin Scott Thomas’ character has a far-ranging conversation with Phoebe Bridgers’ protagonist. One of the profound things she imparts is, “It’s not really a party unless someone flirts with you.” The major downside of getting older, she says, is that “People don’t really flirt with you anymore, not really, not with danger... Do not take that for granted. There is nothing more exciting than a room full of people.” Can we sustain the excitement, the energy, the potential captured in this quotation when AI relentlessly and seductively beckons from stage left, promising a form of connection that involves no risk, danger, or stakes? As Chaucer wrote, “Nothing ventured, nothing gained.”

References

Killian, K.D. (2015). Gods, machines and monsters: Feminist zeitgeist in Ex Machina. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 27(3), 156-157.

Terkle, S. (2023). Artificial intimacy: What are people for? Opening keynote for the conference AI and Democracy, November 30, Science Technology and Society Program, Harvard.