Memory

Memory for Chaos

New research shows that experts do better than novices even with random material

Posted November 9, 2016

Try to memorize the words below:

ROADS NO A HOW FOUR MUST SCORE IMAGINE AGO MANY YEARS MAN SEVEN THERE'S WALK HEAVEN DOWN AND

Most people cannot remember more than nine words. Now, try to memorize the list below:

FOUR SCORE AND SEVEN YEARS AGO IMAGINE THERE'S NO HEAVEN HOW MANY ROADS MUST A MAN WALK DOWN

Although there are 18 words, this is not particularly difficult if you recognize the beginning of the Gettysburg address and verses of John Lennon’s and Bob Dylan’s songs. You recognize patterns in the second list, but it’s much harder to do so in the first.

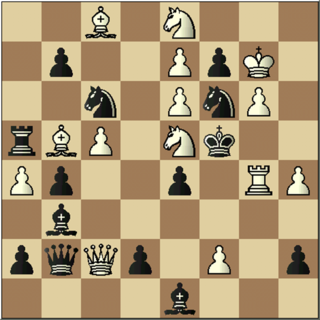

The recall of meaningful and random material has been of great interest in the study of expertise. Ever since the seminal study of Dutch psychologist Adriaan de Groot on chess players in the 1940s, it has been known that experts are better than non-experts at recalling structured material taken from their domain of expertise, even when the presentation time is as short as a couple of seconds. The effect is spectacular – a chess grandmaster can fully memorize the position on the left after seeing it for five seconds. But in a sense, for somebody who possesses the right chess vocabulary, this is not so different from the recall of words organized as a sentence.

This result has been observed in many domains of expertise such as games, music, programming, science, and sports. In most cases, there is a monotonic relationship between skill and the amount of material recalled: the more skilled the individual, the better the recall.

The standard explanation, proposed by Chase and Simon in the early 1970s, is that experts have acquired, as a result of practice and study, a large number of “chunks” (meaningful perceptual patterns) that are stored in long-term memory. When they perceive a scene, they automatically access one or several chunks, which are linked to useful information. For example, in chess, this information could be the move to play or the plan to follow. These chunks can also be used to memorise material – hence experts’ superiority in a recall task.

Messing things up

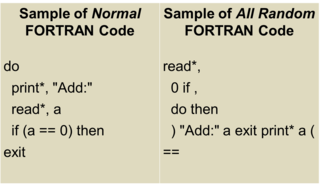

But what happens when the structure of the material is destroyed, for example by randomly placing the pieces on a new square in chess? For a long time, it had been thought that the superiority of the experts should disappear, as there is no structure anymore in the material to memorize, and hence no chunks to recognize. However, in 1996, a study showed that chess players maintain a small but reliable advantage even with these rather chaotic positions (Gobet & Simon, 1996). The explanation for this result was simple: even in random positions, some small meaningful patterns are present by chance, and experts are more likely to recognize them, as they have stored more chunks than novices in their long-term memory. Thus, to go back to our example with a random list of words at the beginning of this article, “must score” and “many years” could be recognised as chunks.

Does this result generalize to other fields of expertise? A recent study (Sala & Gobet, 2016) shows that it is indeed the case. The authors combed the literature to identify all the studies in which experts and novices had to recall random material. Using a technique called meta-analysis – a method that combines the results of different experiments and statistically analyzes them – they found that the effect was reliable, even though the skill difference was small. The difference in recall was particularly large with music, apparently due to the fact that the experiments used relatively simple stimuli. Interestingly, the results were not affected by the presentation duration of the stimuli.

This may seem like an interesting but rather inconsequential result. In fact, the implications of this study are profound. As noted by the authors of the article, many theories of expertise explain the expertise effect in memory tasks by assuming that experts use large memory structures such as schemas or process the stimuli “holistically” – that is, as a single large unit. Other theories postulate powerful memory structures that should apply as well with random material. The first group of theories fail to explain the skill effect with random material because experts cannot use large structures or process the information holistically with such a material. The second group of theories fails because they predict that experts should recall random material too well (see Gobet, 2016, for details).

Thus, it seems necessary to postulate the presence of small memory structures, and the explanation based on chunking seems the best. The validity of this explanation is buttressed by the fact that a computer model using the mechanism of chunking can replicate this effect both with the memory of chess positions (Gobet & Waters, 2003) and computer programs (Gobet & Oliver, 2016).

We started this post by asking you to memorize a random list of words. So, there is an obvious question: Is this effect of expertise present with language as well? Can individuals with better language competencies use their larger store of chunks to memorize random lists of words better than less skilled individuals? Can language be characterized as a kind of expertise? We’ll take up this question in a future post…

References

Chase, W. G., & Simon, H. A. (1973). Perception in chess. Cognitive Psychology, 4, 55-81.

De Groot, A. D. (1965). Thought and choice in chess (first Dutch edition in 1946). The Hague: Mouton Publishers.

Gobet, F. (2016). Understanding expertise: A multidisciplinary approach. London: Palgrave.

Gobet, F., & Oliver, I. (2016). Memory for the random: A simulation of computer program recall. In Proceedings of the 38th Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society.

Gobet, F., & Simon, H. A. (1996). Recall of rapidly presented random chess positions is a function of skill. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 3, 159-163.

Gobet, F., & Waters, A. J. (2003). The role of constraints in expert memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory & Cognition, 29, 1082-1094.

Sala, G., & Gobet, F. (2016). Experts’ memory superiority for domain-specific random material generalizes across fields of expertise: A meta-analysis. Memory & Cognition.