Positive Psychology

Enhancing the Well-Being of Groups Is Hard

Reflections on a mega-analysis of positive psychology interventions.

Posted July 19, 2024 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- When thinking about well-being interventions, systems thinking prompts humility in the face of complexity.

- A new mega-analysis of positive psychology interventions (PPIs) provides perspective in this regard.

- Effects of PPI interventions are generally small- to medium-sized.

- Thinking about these effects from the perspective of dynamic systems theory can be useful.

Much of my work with colleagues focuses on well-being. Recently, for example, we published research findings linking the walkability of neighbourhoods to the happiness of residents. We have conducted experiments on music listening and well-being. We have designed and delivered complex interventions to explore how mindfulness enhances well-being for people living with chronic pain. We have also consulted with citizens in the Design of Wellbeing Measures and Policies, which in turn has informed local and national well-being project work.

When thinking about well-being interventions, I often return to systems science, which always prompts humility in the face of system complexity and the 'requisite variety' of control levers needed to manage systems. Many years ago, I proposed modest systems psychology as a complement to positive psychology, and I developed collaborative positive psychology in response to the challenge of designing systems supporting collective well-being. These foundations prompted our recent work focused on providing training in collaborative system design and our broader reflections on education for collective intelligence.

Learning from a mega-analysis perspective

Enhancing the well-being of groups is not easy. A newly published mega-analysis of positive psychology interventions (PPIs) provides perspective in this regard. The analysis included 198 meta-analyses across 4,065 studies that included a total of 501,335 participants. In essence, the paper provides an overview of effects across thousands of different groups, each of which was facilitated in one way or another by intervention/research teams.

One interesting feature of this mega-analysis is that it included a diverse range of PPIs (i.e., different approaches to enhancing well-being). One category of interventions focused on physical exercise; another focused on mindfulness-based interventions; a third includes mind-body interventions (e.g., yoga, tai chi); and a fourth category includes multi-component interventions that encompass a variety of practices, such as setting valued goals, using signature strengths, practicing kindness, gratitude, optimism, and forgiveness, amongst others. One caveat in interpreting the effects is that these interventions are qualitatively different in important ways, and thus these different approaches to enhancing well-being should not be compared with one another in any simple way. More generally, the dynamics of system change are complex and new research paradigms are needed to model these dynamics in different contexts. Nonetheless, the quantitative effects reported in this mega-analysis are very interesting.

Different types of outcome measures were used across studies included in the mega-analysis (i.e., well-being, quality of life, strengths, depression, anxiety, and stress), and the effects vary a little. Overall, mind-body PPIs (when compared with other PPI types), face-to-face (rather than self-help) delivery, and longer interventions (rather than brief duration interventions) were more effective. But the mega-analysis also makes it clear that effects across all outcomes are generally small to medium-sized effects. More specifically, immediately post-intervention, small to medium-sized effects are observed (i.e., ranging from 0.34 to 0.42 for the six outcomes: well-being, quality of life, strengths, depression, anxiety, and stress), and these effects are smaller again at the seven-month follow-up (i.e., ranging from 0.17 to 0.37 across the six outcomes). For well-being in particular, the average effect across all intervention types are as follows: post-intervention, 0.34; follow-up, 0.23.

Dynamic Systems and Mega-Analysis Effects

The relatively small effects observed for well-being outcomes in this mega-analysis resonate with foundational principles of dynamic systems theory, which includes the idea that system attractors (ways in which the components of a system reliably interact) often resist perturbation (i.e., we are not easily "moved" away from these attractor states). States of well-being are not easy to change.

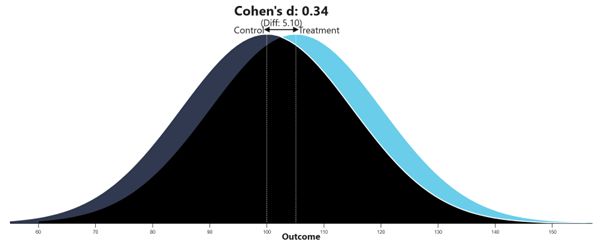

An interactive visualisation created by Kristoffer Magnusson provides a way of thinking about change at a population level. When interpreting well-being intervention (or "treatment") effects at the group level, an effect size of 0.34 looks something like this.

As summarised by Kristoffer Magnusson, with an effect size of 0.34, scores for 63 percent of the treatment group will be above the mean of the control group; 86 percent of the two groups will overlap; there is a 59 percent chance that a person picked at random from the treatment group will have a higher score than a person picked at random from the control group; and in order to have one more favorable outcome in the treatment group compared to the control group, we need to treat 9.3 people on average.

Later, at follow-up (seven months after the intervention), with an effect size of 0.23, 59 percent of the treatment group will be above the mean of the control group; 91 percent of the two groups will overlap; there is a 56 percent chance that a person picked at random from the treatment group will have a higher score than a person picked at random from the control group; in order to have one more favorable outcome in the treatment group compared to the control group, we need to treat 14.2 people on average.

Although we stated the caveat above about qualitative differences between interventions, and although change at the group level can be slow (two steps forward, 0.34, and a small step back, 0.23), the mega-analysis across different well-being interventions does also suggest that many different intervention paths may lead to similar quantitative outcomes. Interestingly, when we look at the effect sizes across different intervention types in this mega-analysis, there is a narrow range of similar, small to moderate effects. From a dynamic systems perspective, this prompts reflection on the equifinality principle (that is, there can be many different ways to achieve the same outcome)—a small movement toward greater well-being.

One final observation relates to the slightly larger mind-body intervention effects (when compared with other PPI types). From a dynamic systems perspective, activities like tai chi and yoga may, by virtue of high levels of activity complexity, simultaneously facilitate multiple pathways of system change. In this sense, they are "complex" interventions. It may be challenging for groups to sustain these practices, but it makes sense from a dynamic systems perspective why larger group effects are observed for the mind-body category of interventions. Psychology is not "all in the head," and activities that engage the body are important for our well-being.

Indeed, our intervention design thinking needs to extend further, beyond the mind and body, to the design of the environment. For example, do we design urban environments in a way that facilitates body movements important for wellbeing? Not always. However, I think drawing upon dynamic systems thinking can prompt a hopeful mega-theoretical perspective here: many well-being system design options remain open to us as part of ongoing, collaborative open system design dynamics.