Fear

Implications for Therapy of Six Simple Brain Principles

Thinking about symptoms as circuit functions might help design better treatments

Posted November 25, 2019 Reviewed by Matt Huston

This is the fifth in a series of posts related to my new book, The Deep History of Ourselves: The Four-Billion-Year Story of How We Got Conscious Brains, which explores mind and behavior, in the context of the four-billion year history of life on earth. These posts, and others, can be found by visiting the home page of my Psychology Today blog, I Got a Mind to Tell You.

Much has been written about the limitations of current approaches available for treating mental and behavioral disorders. The assumption is that new and better approaches can, through more research, be developed. While it is likely that research will continue to suggest improvements, I propose there is a fundamental problem that has hindered progress, and will continue to do so, until it is addressed. I believe that the entire enterprise has been based on a misguided scientific conception, the result of which is a misunderstanding of what underlies the symptoms expressed by people with mental and behavioral problems.

In this post, I suggest several simple principles about the organization of neural circuits involved in mind and behavior that provide a context for understanding how classic, widely accepted psychological concepts have prevented the development of more effective treatments. Emotion-related concepts, especially about fear, will be used to illustrate the implications.

Principles of Brain Organization in Relation to Mind and Behavior

1. All aspects of mind and behavior depend on the brain.

2. The brain is composed on many distinct networks, some of which interact.

3. There are many different kinds of behaviors, and each depends on different brain circuits. Key examples include: reflexes; innate and conditioned reaction patterns; instrumentally acquired habits; instrumental goal-directed actions based on trial-and-error learning; and instrumental goal-directed actions dependent on cognitive modeling—that is, on simulating possible outcomes of actions by using internal representations.

4. It is not always possible to know by mere observation whether behavioral or mental processes underlie a given behavior. In laboratory studies, specific tests determine whether a behavior is habitual or goal-directed; and if it is goal-directed, whether it is based on trial-and-error learning or cognitive simulation of outcomes; if cognitive modeling is involved, still other tests are needed to determine whether non-conscious or conscious processes were involved. Across species, these tests are used to assess which capacities are present in a given species. Within a species, the tests are used to determine which capacity underlies the behavior measured in the particular task utilized.

5. Different behaviors are conserved to differing degrees across mammalian species. Reflexes, innate and conditioned reaction patterns, instrumental habits, and instrumental goal-directed actions based on trial-and-error learning are conserved to the greatest degree. The ability to use simple mental models, such as spatial maps to guide navigation, is also common. Non-human primates have all these abilities, as well as cognitive capacities involving executive functions, memory, and future planning not present, or not present to the same degree, in other mammals. And humans have capacities that are lacking, or less developed, in other primates, especially involving language, hierarchical relational reasoning, and self-awareness (especially the ability to consciously reflect upon one's own existence).

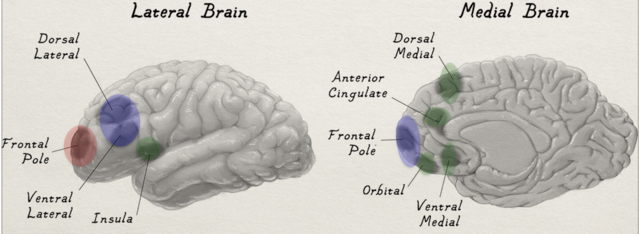

6. The psychological capacities possessed by each group (order) of mammals depends on the brain circuits it possess. Capacities shared by all mammals depend on brain circuits present in all mammals—including subcortical circuits involving areas such as the amygdala, hypothalamus and periaqueductal gray region, and primitive cortical areas located in the medial walls of the hemispheres and in the insula cortex. Unique primate capacities depend on the elaboration of mammalian cortical and subcortical circuits, and also on unique circuits involving regions of the lateral prefrontal cortex not possessed by other mammals. The unique capacities of humans reflect expansions of circuit, cellular, molecular and genetic features of primate and mammalian brains, but also may be related to the fact that we possess a component of the lateral prefrontal cortex with features not found in other primates (the lateral frontal pole).

Implications for Treatment of Mental and Behavioral Disorders

1. The names of mental and behavioral disorders do not reflect biological entities. They refer to collections of symptoms. A common assumption is that there is a fear, anxiety, or depression center or network in the brain that accounts for conditions known by the disorder name. By finding and correcting the pathological condition in that network, the problem will go away. The diseased circuits are searched for by measuring symptoms associated with each disorder. One problem with this approach is that the same symptoms occur in multiple disorders—a given symptom is not a signature of a disorder. More important is the fact that easily measured behavioral symptoms are used to find the circuits, despite the fact that the disorders are named by words related to mental states (fear, anxiety, depression). The circuits identified are thus more often behavioral control circuits, rather than circuits that underlie mental states of fear, anxiety or depression.

2. Symptoms can be understood in terms of the behavioral categories and networks described above. A focus on symptoms allows a systematic approach to understanding symptoms. It does not reveal latent disease states that account for the pathology that explains the root of all the symptoms associated with the condition, given that the same symptoms can occur in multiple disorders. Another problem is that since different symptoms reflect different behavioral and/or mental capacities, knowledge of the molecules and genes in circuits underlying behavioral symptoms associated with uncontrollable fear or anxiety (such as excessive freezing or avoidance) does not necessarily generalize to the corresponding subjective symptoms (such as feeling afraid or anxious) that name the disorder.

3. The two main scientific approaches to treatment, pharmaceutical and behavioral/cognitive approaches, both have their origins in 1940s behavioristic conceptions that marginalized mental states as explanations of behavior. Although the behaviorists had eliminated mental states as causes of behavior, they unfortunately retained mental state terms like fear, and operationalized these as a relation between stimuli and responses. In this tradition, fear was a hypothetical factor, not an actual state of mind or brain. This has caused no end of confusion about the implications of findings about fear, since seldom is the difference between behavioral fear and subjective fear made. This was discussed in The Deep History of Ourselves and in other posts in this blog.

4. The pharmaceutical approach used easily measured, relatively primitive, behavioral symptoms in animals to find solutions for complex psychological problems in humans. By the middle of the 20th century, some behaviorists began looking for the physiological basis of states like fear and hunger, and the hypothetical fear state became a physiological brain state that connects danger to behavior. Objectively measurable responses (conditioned behaviors, body physiology, brain arousal) were viewed as the most direct way to measure the physiological fear state. If subjective fear was mentioned, it was treated as an additional output of the physiological fear center that generates the fear state, but was of little concern.

In pharmaceutical research, tests of innate or conditioned reactions, and/or learned instrumental actions, were used. The assumption was that medications that changed animal behavior did so by changing the physiological state that controlled the behavior. Because subjective fear is also an output of the fear physiological state in the fear network that is conserved across mammals, it was also assumed that medications that change fear behavior in animals would also change human fear behavior and subjective feelings of fear. By 2010, it was beginning to be clear that the decades-long effort had failed, as treatments developed through such studies were rarely resulting in novel products with clinical efficacy in humans.

5. Ultimately people want to feel better subjectively—they want to feel less fearful, anxious, or depressed. One possible explanation for the shortcomings of medicinal treatments is that these feelings are not in fact products of the primitive circuits that control behavioral and physiological responses in all mammals. I and a number of other contemporary researchers have proposed that emotional feelings are the result of one's cognitive interpretations of situations, and depend on higher-cognitive processes that are likely unique to humans. These reflect circuits in the kinds of brains we have, and cannot be understood by measuring innate and conditioned behaviors that don't depend on these circuits.

6. Perhaps cognitive approaches are the answer. Behavior therapy, based on principles of Pavlovian and operant conditioning, was initiated by behaviorists in the late 1950s. In the 1960s, cognitive behavior therapy emerged by blending behaviorist principles, such as habituation and extinction, with cognitive principles, such as expectancy, and giving greater emphasis to the role of thoughts and emotions in behavior. Another development was cognitive therapy, which placed greater emphasis on cognitive targets (schema, automatic thoughts, beliefs) as the road to behavior change. But because these efforts were traditionally focused on disease state-based diagnoses, the goal of treatment was to reduce this disease entity.

With the rise of positive psychology and mindfulness approaches, and new ways of thinking about behavioral and cognitive therapies, subjective states gained a more prominent place. While the various approaches have been shown to be more effective than placebo, at least in the short-term, none is considered a panacea.

7. Conscious emotional experiences depend on specific cognitive processes. Most therapeutic approaches assume that subjective well-being will result as a byproduct of other changes that can be objectively measured by behavioral responses. As we've seen, behavioral responses differ in function and circuitry. Pharmaceutical treatments that target innate or conditioned reactions and actions are not likely to be ideal for changing feelings. But the fact that cognitive approaches that target higher levels of behavioral control are not necessarily any more effective suggests that they, as currently implemented, may not be the final answer either.

This may be because conscious emotional experiences do not arise from any and all cognitive processes. They have specific requirements. In my model, these include the non-conscious merging of emotion- and self-schema, so that one's self is the subject of the conscious emotional experience. If YOU are not aware that it is YOU who is about to be harmed, YOU will not feel fear. You may be behaviorally agitated, and/or highly aroused without being subjectively aware, but fear is your awareness that YOU are in harm's way—"no self, no fear."

8. To change subjective well-being it may be necessary to make subjective well-being the goal. It may not be enough to assume that subjective feelings will automatically change as a result of cognitive changes in general.

9. This is not to say that subjective well-being is totally ignored. All therapists presumably want their clients/patients to feel better. But the question is how to achieve that. In people with psychological problems, maybe the range of subjective experience has been narrowed, making it harder to change than behavioral and physiological responses. Maybe it becomes one's inner problem child in the sense that it needs more attention than its more compliant cognitive and behavioral siblings. But because those siblings can be disruptive in their own way, they may need to be attended to first. Then, with their needs taken care of, it might be easier to give the more rigid emotion itself the attention it needs.

Acknowledgments: Many thanks to Stefan Hofmann, Dennis Tirch, and Nancy Princenthal for comments on drafts.

Some relevant literature.

- Balleine BW, Dickinson A (1998) Goal-directed instrumental action: contingency and incentive learning and their cortical substrates. Neuropharmacology 37:407-419.

- Bandura A (1969) Principles of behavior modification. New York: Holt.

- Barlow DH (1988) Anxiety and Its Disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. New York: Guilford.

- Barrett LF (2017) How emotions are made. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Beck AT (1991) Cognitive therapy. A 30-year retrospective. Am Psychol 46:368-375.

- Beran MJ, Menzel CR, Parrish AE, Perdue BM, Sayers K, Smith JD, Washburn DA (2016) Primate cognition: attention, episodic memory, prospective memory, self-control, and metacognition as examples of cognitive control in nonhuman primates. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci 7:294-316. PMC5173379.

- Clore GL, Ortony A (2013) Psychological Construction in the OCC Model of Emotion. Emotion Review 5:335-343.

- Craske, Michelle G. (1999). Anxiety disorders : psychological approaches to theory and treatment. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Dickinson A (1985) Action and Habits: The development of behavioural autonomy. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B, Biological Sciences 308:67-78.

- Ellis A (1957) Rational psychotherapy and individual psychology. Journal of Individual Psychology 13:38-44.

- Fanselow MS, Pennington ZT (2018) A return to the psychiatric dark ages with a two-system framework for fear. Behaviour Research and Therapy 100:24-29. PMC5794606.

- Hayes SC, Follette VM, Linehan MM (eds.) (2004) Mindfulness and Acceptance: Expanding the cognitive-behavioral tradition. New York: Guilford Press.

- LeDoux J (2012) Rethinking the emotional brain. Neuron 73:653-676.

- LeDoux J (2019) The Deep History of Ourselves: The four-billion-year story of how we got conscious brains. New York: Viking.

- LeDoux J, Brown R, Pine DS, Hofmann SG (2018) Know Thyself: Well-Being and Subjective Experience. In: Cerebrum New York: The Dana Foundation.

- LeDoux J, Daw ND (2018) Surviving threats: neural circuit and computational implications of a new taxonomy of defensive behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci 19:269-282.

- LeDoux JE (2014) Coming to terms with fear. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:2871-2878.

- LeDoux JE (2015) Anxious: Using the brain to understand and treat fear and anxiety. New York: Viking.

- LeDoux JE (2017) Semantics, Surplus Meaning, and the Science of Fear. Trends Cogn Sci 21:303-306.

- LeDoux JE, Brown R (2017) A higher-order theory of emotional consciousness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:E2016-E2025.

- LeDoux JE, Hofmann SG (2018) The subjective experience of emotion: a fearful view. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 19:67-72.

- LeDoux JE, Pine DS (2016) Using Neuroscience to Help Understand Fear and Anxiety: A Two-System Framework. Am J Psychiatry 173:1083-1093.

- Lindsley O, Skinner BF, Solomon HC (1953) Studies in behavior therapy: Status report. I. Waltham, MA: Metropolitan State Hospital.

- Mobbs D, LeDoux J (2018) Editorial overview: Survival behaviors and circuits. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 24:168-171.

- Pine DS, LeDoux JE (2017) Elevating the Role of Subjective Experience in the Clinic: Response to Fanselow and Pennington. Am J Psychiatry 174:1121-1122.

- Preuss TM (2011) The human brain: rewired and running hot. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1225 Suppl 1:E182-191. PMC3103088.

- Russell JA (2014) The Greater Constructionist Project for Emotion. In: The Psychological Construction of Emotion (Barrett, L. F. and Russell, J. A., eds) New York: Guilford Press.

- Semendeferi K, Teffer K, Buxhoeveden DP, Park MS, Bludau S, Amunts K, Travis K, Buckwalter J (2011) Spatial organization of neurons in the frontal pole sets humans apart from great apes. Cereb Cortex 21:1485-1497.

- Wolpe J, Lazarus AA (1966) Behavior Therapy Techniques: A guide to the treatment of neuroses. Oxford: Pergamon Press.