Career

Going Back to the Office, and Bringing Baggage

The world is a different place now. Workplaces should be, too.

Posted August 16, 2021 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Psychologists know that periods of transition are the most stressful moments of our lives.

- Understanding employees' concerns, and showing compassion, will go a long way toward easing the transition back to the office.

- Managers can help ease the transition by allowing workers to ramp up to their pre-pandemic office schedules.

- The lessons we learned during the pandemic could help us create more inclusive workplaces for the future.

The potted plants are dead and the office fridge has become a science experiment. Many white-collar workers were fortunate to work from home during the pandemic, safely away from colleagues and their droplets. Now, nearly 18 months after saying goodbye to cubicle life, many of us are trickling back to the office.

Although the rampaging spread of the delta variant has delayed the return of workers at some large companies, including Amazon, Google, and Lyft, others, such as J.P. Morgan Chase and Goldman Sachs, are proceeding with office reentry as planned. It hasn’t been a joyful reunion for everyone, and not just because it has meant finding the ossified remains of the banana we left on our desk in March 2020.

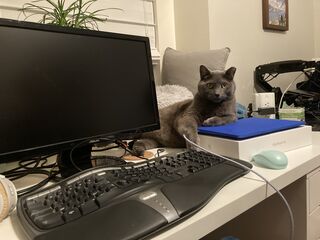

I returned in July, with mixed emotions, to the Rice University campus, where I edit the alumni magazine for Rice’s Jones Graduate School of Business. On the one hand, the 1,000-square-foot house I share with my partner and our 18-pound cat has felt increasingly cramped with the three of us always in it, especially when one of us yowls for attention and pukes on the rug. So I was looking forward to coming back to an actual workspace with limited yowling.

But there were drawbacks. Out of practice, I took forever to get ready for work. The commute felt interminable. And as my colleagues and I soon discovered, nearly all of the office electronics had inexplicably broken down during our absence. The printer wouldn’t print; the fridge wouldn’t refrigerate. I found myself missing the comforts of home. And my cat.

Experts say I’m not alone in having reservations about returning to the office. For some, remote work provided perks they don’t want to give up. For others, a year of working from home was a slog, and they’re burned out. For all of us, the COVID-19 pandemic was a traumatic experience, and it will take time to get back to “normal”—which may never look the same. So how can managers better manage the return to in-person work for employees who may not be thrilled to be back?

First, acknowledge that this is a tough time—for everyone. Psychologists know that periods of transition are the most stressful moments of our lives. “Change is hard,” says Mikki Hebl, a professor of psychology and management at Rice’s Jones Graduate School of Business. The pandemic has upended all of our lives, whether or not we or our loved ones got sick, due to isolation, lost jobs, food insecurity, or just plain uncertainty.

At the same time, we’ve also gone through what Hebl calls a racism pandemic, with high-profile acts of violence against Black and Asian Americans. “The effects are certainly worse for Blacks and Asians, but research suggests members of every racial group have heightened stress regarding racial tensions,” she says.

The twin pandemics combined have taxed the mental health and coping skills of all Americans. “When that happens, people start acting defensively and in their own self-interest,” Hebl says. “A smart manager will, first, understand the problem; second, address it; and third, give space for conversation and coming together.”

Don’t assume you know what your employees are going through—or that their anxieties are the same as yours. For example, a new survey from Project Include revealed that workplace harassment paradoxically increased while people were working from home during the pandemic. More than a quarter of respondents experienced more gender-based harassment and 10 percent experienced more race-based harassment while working remotely.

Ellen Pao, Project Include’s CEO, said the survey’s results show how deeply rooted discrimination has been in our workplaces since long before the pandemic struck. “There was a lot of sexism, transphobia, xenophobia, and all sorts of systemic bias in the tech sector, in business sectors generally, and in individual companies. COVID made it worse—COVID didn’t magically solve those problems,” Pao said in an interview with the company Charter. “The big learning we had is people will harass people and be hostile to people no matter what the environment. They will find a way.”

Workers who are experiencing harassment will be even less likely to look forward to reuniting with their coworkers in person, a situation managers need to be ready to defuse, Hebl says.

“They should be open and available to hear about traumas their employees are experiencing, from COVID-related deaths in their family to trauma related to ‘working while Black,’” she says. “They should allow for check-ins about how people are doing—what psychological spaces they are in and where else their mind might be.”

Understanding these issues, and showing compassion, will go a long way toward easing the transition back to the office, says Boris Groysberg, a professor of business administration at Harvard Business School. “As the COVID-19 pandemic starts to wane, we cannot expect to wake up one day and find our lives miraculously restored to what they were in pre-pandemic times. We will all be forever changed by this experience, and the transition to a post-pandemic world will be a slow and rocky one,” Groysberg said in March.

The pandemic has dragged on for so long that we’ve all had plenty of time to acclimate to our new normal, which for many of us included remote work. So even if working from home was difficult at first, we’ve fully adapted to it by now, says Kate Sweeny, a psychology professor at the University of California, Riverside. That has made returning to our old offices an unfamiliar and potentially uncomfortable prospect. But there are ways to manage the anxiety that comes along with uncertainty. “It helps to plan ahead to gain a sense of control over an uncertain future,” Sweeny says. “Second, you can look for the good in returning to work. Are there coworkers you’ve missed? Old routines that will be a welcome relief?”

Managers can help ease the transition by allowing workers to ramp up to their pre-pandemic office schedules, perhaps by working in person a day or two a week to start. And companies should consider building in more flexibility for employees who need it even after the pandemic is well behind us, Hebl says. The world is a different place now—and so are workplaces.

“We can’t just go back to two years ago and pick up where we were. Our world, our workforce has changed. And some of it will ultimately evolve into changes for the better,” she says. “For instance, many individuals — let’s take individuals with physical disabilities and new mothers, who often get only two weeks of unpaid leave to care for their babies, as examples —should have long ago been given greater flexibility, support, and pay to work from home. Shorter workweeks, job sharing and flex work are temporary strategies that worked well during the pandemic and should not be abandoned as possible ways for organizations to be flexible.”

Many caregivers and people with disabilities saw the opportunity to work remotely as a silver lining of the pandemic. Take Ruby Jones, a British disability activist who has a connective tissue disorder called Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, which limits her mobility. She created a Twitter hashtag, #MyAccessiblePandemic, to highlight the ways the pandemic improved accessibility for disabled people. “Working from home means I am able to work a full-time job without exhausting myself to the point of hospitalization,” she tweeted.

A chorus of other voices chimed in, including people with physical disabilities and mental illness. “WFH means I can adjust my sleep/awake schedule as necessary to match my chronic fatigue cycles,” one person commented. “I've been able to attend really interesting talks, events, and conferences I never would have been able to manage in person. I can switch my camera off if it gets too much and been able to type questions when my anxiety is high rather than have to speak,” tweeted another.

Some of the lessons we learned during the pandemic could help us create more inclusive workplaces for the future, Hebl says. We can do that by combining some of the highlights of our old normal—such as connecting with coworkers and exchanging ideas face to face—with a new normal that includes compassion and accommodation for those who need more flexibility to succeed. And flexible schedules for everyone could mean we all get to spend a little more time with our cats, for better or worse.

A version of this also appears in the Houston Chronicle.