Social Networking

Does Facebook Make People Unhappy?

A new study synthesizing information from almost 1 million people gives answers.

Posted August 21, 2023 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Congressional testimony, documentaries, and media suggest social media like Facebook causes unhappiness.

- New research synthesizes data from Facebook and Gallup on almost 1 million people to estimate this connection.

- The researchers find that increasing Facebook use in a country is not associated with negative outcomes.

- Overall, there's no one big effect of Facebook on well-being. More detailed analyses are needed.

Social media, in general, and Facebook (now called Meta), in particular, have been linked to problems in society in recent years. In Congressional testimony, a former Facebook employee acted as a whistle-blower, revealing that internal analyses suggested that more Facebook use was associated with poorer mental health. The use of Instagram—a platform also owned by Facebook—was related to young girls developing eating disorders. YouTube has been associated with the radicalization of political beliefs, especially those related to white nationalism and the alt-right. White nationalists now pose the largest terrorist threat to U.S. citizens.

It seems like one of the broad takeaways from research and the national conversation around social media in recent years is this: Social media, particularly Facebook, is bad for people.

But is that true?

Newly published research combines data from Facebook and Gallup to examine the link between Facebook use and well-being across 72 countries. This dataset synthesizes information from close to 1 million people, representing an enormous sample that can provide very good estimates of the association between well-being and Facebook use. Before I reveal their conclusions, let me explain how they did the study. If you were in one of the university classes I taught, I would ask you to think—as you read—about what you predict the outcome of the analysis would be. Given how the researchers did their study, what would you expect?

The researchers measured Facebook use across countries using data from Facebook on Daily Active Users (DAUs) and Monthly Active Users (MAUs). These are what you’d expect: the number of people logging in daily and monthly from a given country. (If you’re playing along, you might be considering now what that’s missing. Does it capture how long they spend on the platform? What kind of content—political outrage, photos of friends’ perfectly curated lives, silly memes and puns, etc.—are people seeing and engaging with?)

The researchers measured well-being through several questions collected by Gallup. The well-being measure was a single question, essentially a 10-point rating scale, on how happy you are with your life. They also measured positive and negative daily experiences. These questions asked about experiences the day before.

Given enough interviews conducted on enough random days, this method should be able to capture how people’s daily lives tend to be in general in a given country. Positive questions asked things like, “Did you smile and laugh a lot yesterday?” Negative questions asked things like, “Did you experience worry during a lot of the day yesterday?”

Again, if you’re playing along at home, consider what this study is and isn’t capturing. It’s not looking at mental health outcomes—which has been a key point related to people’s negative opinions about Facebook. It’s also not looking at specific problematic—or positive—attitudes people might develop on Facebook. So they didn’t ask whether people had less trust in public institutions or less trust in their neighbors and community. They also didn’t ask whether people felt like they had good coping skills or were better informed.

The analysis looked at the relationship between Facebook use and well-being across 72 countries from 2008 to 2019. If Facebook use was higher, did people have higher or lower well-being in that country and year? They could do this within a country—meaning, as a country gained more Facebook users, did well-being start to decline? They could also do this between countries—meaning, did the countries with more users have lower well-being than those with fewer users?

I’ve walked through the details of the study because the results are surprising—especially to someone who’s been following the media narrative developing around Facebook over the years. As countries gained more Facebook users, there was no change in well-being, the number of positive experiences, or the number of negative experiences. Facebook didn’t make things worse.

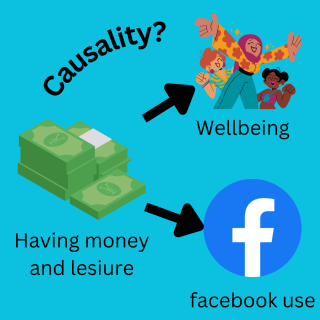

When you look between countries, the results are also striking: Countries with more Facebook users had more well-being, more positive experiences, and fewer negative experiences. This might tempt us to say that Facebook actually improved countries where it was adopted, but the researchers were careful to point out that this is probably not the case. Rather, rich countries where people have a lot of access to technology and free time to use Facebook were both more likely to have more Facebook users and to experience greater well-being. But that’s likely because of their money and free time, as opposed to because of the great benefits Facebook provides.

So is Facebook a problem?

Does it disrupt society and cause mass unhappiness? The simple answer is that, on the whole, Facebook itself is not good or bad. When all of the aspects of Facebook are considered together, we don’t find that it makes people any more or less happy.

But think about what considering Facebook as a whole involves. Using Facebook means watching political rants and seeing violent images and rhetoric about political outgroups—but it also means getting to see your newborn nephew and marvel at how quickly he grew in his first month of life. Using Facebook means comparing yourself to professional photoshoots of your high school classmate’s engagement—but it also means seeing that your work friend’s band played a good gig at a bar near your apartment.

There isn’t one clear effect of Facebook because Facebook is a platform that has all kinds of communities and niches. Negative effects from angry content are being averaged in with positive effects from keeping up with friends, which are also being averaged in with neutral content, like a birthday reminder or a meme that didn’t really resonate with you. This study suggests that banning Facebook overall isn’t likely to improve people’s quality of life. Instead, we will have to get a bit more nuanced in what aspects of Facebook and what patterns of use do and don’t contribute to well-being.

References

Vuorre, M., & Przybylski, A. K. (2023). Estimating the association between Facebook adoption and well-being in 72 countries. Royal Society Open Science, 10(8), 221451.