Media

The Media Feeds Our Fears

We’re bombarded by negative news, causing us to be more fearful than we should.

Posted December 27, 2021 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Fear is a basic human emotion, hardwired into us as human beings. From an evolutionary perspective, fear was essential to human survival. Fear results from the presence of situational cues that we interpret as potentially threatening. It isn’t the situational cues themselves that produce the fear, it’s how we interpret those situational cues. That's where our past experiences, both direct and vicarious, come into play. They help us to make sense of a situation.

The sensemaking process, though, seldom leaves us perfectly confident in a conclusion. This opens the door to probability—the probability that a given situation represents a threat. While it may be easy to make arguments based on quantifiable probabilities, often, when we are discussing human decision-making, it is the subjective assessment of likelihood, as opposed to actual probability, that guides our actions. Are we confident enough in a specific conclusion to decide?

When it comes to the question of judging whether or not someone else is a threat, we rely on situation-specific information to determine whether a situation matches an existing threat prototype derived from direct and vicarious experience. If a situation matches a threat prototype, we’ll conclude that the situation represents a threat and act based on this judgment. For example, if you’re in a bank and an individual walks in wearing a mask and carrying a gun, such a situation likely represents a perfect match to an existing threat prototype.

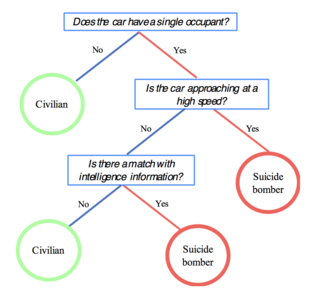

Unfortunately, few situations represent exact matches. The lack of an exact match requires that we make judgments based on incomplete information. We’ll rely largely on heuristics[1], such as fast-and-frugal trees, to determine whether the situation is indeed a threat (see Figure 1 for an example used by the U.S. military to discriminate possible car bombers from civilians at checkpoint).

But there’s an added issue when it comes to threat detection: errors are not equivalent. There are, as Haselton and Galperin (2011) argued, often drastically different consequences that come from making a false positive error (concluding a situation is threatening when it isn’t) than a false negative error (concluding a situation is not threatening when it actually is). As such, unless we’re confident a situation isn’t a threat, we tend to be more willing to make a false positive error than a false negative error (like the expression “erring on the side of caution”).

In many situations, fear-based threat conclusions merely lead to avoidance behaviors. If you’re unsure whether a snake is poisonous, you may conclude it’s better to assume so and simply steer clear of it. If you’re unsure whether the stranger approaching you is a threat, you may conclude it’s better to assume so and cross the street.

In other situations, fear-based threat conclusions can lead to more aggressive actions. If you see a spider, you may not avoid it. Instead, you may judge the spider to be enough of a potential threat that you step on it[2]. But erring on the side of the false positive can result in tragic consequences when aggressive actions are taken, such as the killings of Trayvon Martin or Tamir Rice. In such situations, acting based on too little evidence can be just as disastrous as waiting to act until it is too late.

So, it’s important to remember that:

- The consequences of false positives and false negatives matter. When the consequences of a false positive are benign or nonexistent, it may be better to err on the side of the false negative. That is, we don’t need to be overly confident before we decide to act. However, when a threat may call for aggressive action, false positives can be as disastrous as false negatives and greater confidence may be warranted.

- Application of heuristics based on a faulty threat prototype can lead to erroneous decisions. In the case of Trayvon Martin, George Zimmerman’s threat prototype was based more on stereotypes of young black men in hoodies than it was on any actual evidence of a threat. But threat prototypes can also be flawed in the sense that they fail to allow us to identify a threat quickly enough, leading to disastrous false negatives when there’s a failure to act when a threat is present.

- Reliance on fewer situational cues may lead to faulty conclusions. A single strong cue can be misinterpreted (as it was in the case of Tamir Rice), and there may be other relevant, but weaker, cues that may be missed merely because of the presence of a single strong cue[3].

The Media’s Role in All This

Most media stories involve reports of events, and the vast majority of those reports are negative. The reason for this is that negative news tends to generate a lot more clicks than positive news.4 We’re motivated to be wary of information that can adversely affect us, and negative news stimulates that motivation.

The problem, though, is that constant exposure to negative information about certain topics can skew our frames of reference, leading to an overrepresentation of potential threats. This constant exposure has significant repercussions. It can cause us to overestimate the probability of a given threat, such as the likelihood of having adverse effects from COVID or from vaccines. It can lead us to make broad generalizations about others based on extreme examples, such as protestors, police officers, or people who voted differently from us. And that poses problems for our future decision-making.

References

Footnotes

[1] Although there may be some situations where we can engage more deliberative decision-making processes to make a more informed decision, in many instances where threat appraisals are made, such decisions come with a finite decision-making window.

[2] Unless it’s a really big spider, and then you might still run away or make someone else kill it.

[3] This is, in some ways, a more generic application of a weapon focus.

[4] One Russian newspaper sought to spend an entire day only reporting positive news. It lost two-thirds of its readers that day.