Play

A Risky Gamble or an Uncertain Future?

Both risk and uncertainty play critical roles in gambles we make.

Posted December 11, 2020

Very few decisions we make have a 100% chance of working out the way we want them to. Instead, as I mentioned in an earlier post, we often make decisions based on how we assess the costs and benefits, the likelihood of the incurred costs leading to the desired benefits, and whether that likelihood is sufficiently satisfactory for us to take the gamble.

One of the topics we discuss in a course I teach on Ethical, Evidence-Based Decision Making is the difference between risk and uncertainty. One of the students in a recent class mentioned the desire for a resource to more fully explore this issue and how it affects decision making. This is an attempt to fill that need.

Risk

Risk exists when the probability that our invested resources will produce the expected benefit is less than 100%, or when there is some probability that the invested resources will bring about some specified negative outcome. It would be easy to say that almost no decision is ever 100% likely to work out, which would be a true statement. However, a risk is more specific than that because it possesses a few important characteristics.

First, it is reasonably quantifiable. We can reasonably estimate, for example, the probability of winning the lottery, the probability of dying in a plane crash, and the probability of winning a hand of blackjack. These are all quantifiable probabilities, and, at least in a general sense, they can be calculated.

Second, the amount of risk may be adjusted upward or downward based on knowable factors. As the comedian Michael McIntyre pointed out in his 2020 special on Netflix, while the probability of dying in a shark attack off the coast of Australia may be quite low, it is 0% if you choose not to swim there. Therefore, we can make decisions that either reduce or increase our risk of not bringing about the expected benefit or our risk of bringing about an undesired consequence.

It is important to remember, too, that while risk is generally quantifiable or estimable, we don’t always know the exact percentage of risk that exists in a particular decision, leaving us only the option of guessing at the level of risk, the perceived level of risk[1]. As such, we tend to make many decisions based on our subjective perceptions of risk rather than actual risk probabilities.

For example, we can reasonably assume that the risk of getting into a car accident increases in poorer weather conditions[2], but how much higher that risk is may be a function of several factors, such as time of day, time of year, and driver age and experience. Most drivers recognize increased risk in poorer weather conditions and either (1) tend to be more cautious when driving in such conditions or (2) reduce how much they drive during those conditions. The greater the perceived risk, the greater the likelihood they will take more extreme steps to reduce that risk.

Newly identified risks, recent negative experiences, and traumatic events[3] may all make various risks more salient. More salient risks tend to cause us to be more deliberative about how we reduce the likelihood they will occur, though we may also be more likely to overestimate their probability. Overestimation may cause us to engage in more extreme choices to minimize risks, leading to a form of loss aversion[4].

Once risks become less salient, they tend to operate in the background, sometimes leading us to automatize behaviors consistent with the goal of risk reduction[5], such as putting on a seat belt. Other times, we may behave as if the risk is minimal or nonexistent, such as any situation where we become careless because nothing bad has ever happened.

Uncertainty

Whereas risk is quantifiable and can be estimated, uncertainty is simply unknown. We don’t know what the future holds. We can describe uncertainty as indeterminable or indefinite. For example, a company doesn’t know what its industry will look like in five years. Thus, any attempt to develop a five-year plan will necessarily be limited based on the assumptions that are made about the future (e.g., regarding regulation, market size, competitive landscape). Different assumptions can be used to help design future possible scenarios, but there is no way to know how likely or unlikely any of those scenarios are to come to pass.

We can, however, be aware of different sources of uncertainty. What this means is that we can identify some factors that are likely to affect our decision making, even if we don’t know enough to know how they will affect us. For example, we know that COVID vaccines are in the process of being released and that these vaccines are likely to have some impact on decisions we make in the next six months to a year. At this time, though, we don’t know enough to know how they will affect our decision making. As such, the best we can do is either:

- Determine what we assume the impact of the vaccine will be and commit to decisions based on that assumption or

- Take a wait-and-see approach before committing to any decision.

Both options are a gamble based on what is currently an unknown probability, and both come with potential costs and potential benefits.

For example, let’s say you assume life will return to normal in six months and subsequently begin making airfare and hotel reservations for a trip to New York City. If your assumption turns out to be wrong, you may lose some amount of the money you spend on those reservations.

On the other hand, if you assume the world won’t be back to normal in six months and you’re wrong, by the time you realize you were wrong, you may end up paying much higher prices for your trip or have difficulty getting reservations where you want to stay.

In this example, taking a wait-and-see approach may result in similar outcomes as if you had assumed the world would not be open, but you may be quicker to alter your tactics if it looks like it will. Thus, you may get better airfare rates or have more options in terms of hotel reservations. You could also begin to plan for multiple scenarios, though you run the risk of expending time and effort planning for scenarios that do not come to pass.

Why All This Matters

Though it might seem as though the difference between risk and uncertainty isn’t all that meaningful, it actually can be quite impactful. We often make decisions in a way that confounds risk and uncertainty.

To assume that risk is unpredictable (or to fail to be aware of it) may cause us to take needless risks. In other words, we may accept risks that would be ill-advised, or we may fail to take reasonable steps to reduce our risk.

To attempt to translate what is uncertain into a probability often results in wildly erroneous estimates of risk. This could lead us to make decisions that are either overly risk-averse or overly risk taking[6]. Instead, it might be more advisable to either plan for multiple scenarios or take a wait-and-see approach until some of that uncertainty becomes more predictable.

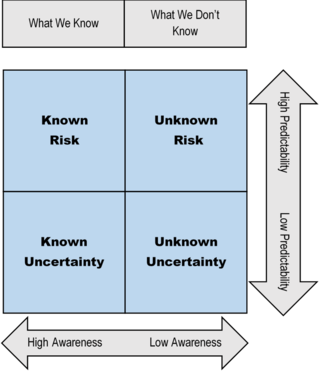

As such, we need to be careful about what we know and what we don’t know. While this sounds obvious, it means half the matrix presented in Figure 1 could be composed of factors that may affect our decisions even though we are unaware of them. For many relatively trivial decisions, there may not be much of a reason to explore and expand our understanding of the situation before we choose to act (or not).

But for decisions in which there are subjectively high costs of being wrong, it is incumbent upon us to do two things. First, we should do what we can to make what is reasonably knowable known by seeking additional, credible information to help us better understand the risks and uncertainties in our decision. Second, we should differentiate what is predictable (i.e., risk) from what is unpredictable (i.e., uncertainty). We can often take some steps to ensure a satisficing level of risk, but if we don’t differentiate risk from uncertainty, we often sabotage our decision-making in two ways

- We fail to take steps to reduce predictable risk, thus allowing chance to play a larger role than necessary,

- We take steps to reduce risks that don’t actually exist, potentially decreasing the probability of a satisficing cost-benefit trade-off.

Therefore, when the stakes are high, it is beneficial to be more deliberative about risk and uncertainty.

References

Footnotes

[1] This is often a very subjectively derived estimate, sometimes being much higher or lower than would result from a more objective risk analysis.

[2] Statistically, you actually have a higher probability of getting into an accident in the summer months, but given that 17% of all vehicle crashes occur during winter road conditions and 73% of accidents occur on wet pavement, it is difficult to dispute the conclusion that poorer weather conditions increase accident likelihood.

[3] Covid-19 would fall into the category of newly-identified risks; having a car accident in the last couple of weeks would be an example of a recent bad experience, and having been in car accident where you were injured while driving in snow would be an example of a traumatic event.

[4] It doesn’t necessarily mean we won’t choose that option. For example, it doesn’t mean we will never drive in the snow again, but it may mean we are more selective about when we choose to do so or allow others to drive when possible.

[5] Sometimes, though, our attempts at risk reduction may not have their intended effects, such as in the case of parents opting out of vaccinating their children.

[6] Interpretations of the Oxford Imperial Model regarding COVID back in March 2020 was a demonstration of this, as pointed out by Philippe Lemoine.