Health

Middle-aged Americans are Dying Younger: Why?

But it's restricted to one group

Posted June 3, 2016

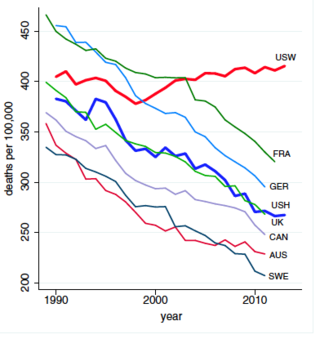

Long-term mortality rates in the USA showed a steady decline between 1970 and 2013: about 40%. But recent data[1] shows that this doesn’t apply to some middle-aged Americans. Up until 1998, this group had shown the same improved mortality as in other rich countries. In these countries, this trend continued after this date, but not in the USA. Mortality rose by about half a percent per year: but only in white non-Hispanics. Hispanics continued to follow the trend of other countries. These increasing death rates in white non-Hispanics are specific to middle age. It’s calculated that about 490000 deaths would have been avoided between 1998 and 2013 had this trend in the USA not occurred. Moreover, it seems that it’s a trend that is unique to the USA. So what lies behind it?

There seem to be three causes. Suicide, drug and alcohol overdose and (somewhat related) chronic liver disease such as cirrhosis. Other common causes of death and ill-health are lung cancer and diabetes, but these do not seem to contribute. It’s interesting that the obesity ‘epidemic’ is not (yet) reflected in increasing early mortality. Deaths by overdose overtook lung cancer in this group in 2011, and suicide may do so if the present trend continues. The increasing mortality for white middle-aged non-Hispanic Americans appears even more striking when compared to other groups. For example, over the 15year period analyzed, midlife mortality (per 100000) for black non-Hispanics fell by more than 200, and by more than 60 for Hispanics; it rose by 34 in white non-Hispanics. So using this group and a standard or benchmark to measure optimal survival rates for other groups (eg blacks) is now highly questionable.

More detailed analysis of mortality in white non-Hispanics showed that it applies to both males and females. Neither was the region of the USA important: much the same trend was observed in the south, east, midwest and northeast. But education seems to have been a major factor. Those with a bachelor’s degree or higher actually showed a decreased mortality from suicide, cirrhosis and overdoses, but those with least education (less than high school or HS degree only) had a four-fold increase. This trend may not be limited to the middle-aged: there is preliminary evidence that it may be occurring in 30-34 and 60-64 age groups as well.

But the data for this group of middle-aged Americans is very striking. Look at the graph: It shows a consistent fall in mortality for many countries comparable to the USA, and in groups other than white non-Hispanics in the USA. It’s a steady trend, so it can’t be explained away as a temporary aberration. (USW: white American non-Hispanics; USH: American Hispanics. Other countries as indicated)

The increasing death rates in middle-aged white non-Hispanics are reflected in a decline in general health. There was a fall, over the same period, in the fraction of this group reporting excellent or good health and, of course, an increase in those reporting fair or poor health. In particular, reports of chronic pain (neck, face, joints, sciatica) rose. So, too, did reports of mental illness, which would be expected to have an impact on suicide rates. This increased by 23% over the 15 year period. There may have been improvements in detection and diagnosis of mental illness over the same period, which may, to a degree, account for this finding. Overall, increased ill-health could well have been detrimental to employment: the proportion of white non-Hispanics unable to work doubled over 15 years. So, too, did the risk for heavy drinking.

The underlying causes for this worrying trend are not fully understood. Cheaper and easier access to drugs (both legal and street) may play a part, given the increased incidence of overdosing. More pain may encourage drug use, and is a known risk factor for suicide, which accounts for some of the increased mortality. Since both drug use and alcohol intake are life-style choices, the authors wonder if economic conditions might play a part. Increased mortality in this group was most marked in those with least education, and therefore occupying lower-skilled jobs. It is just this group that has seen little or no improvement in real earnings over that past 20-30 years or more in the USA. Together with alterations in pension plans, the authors speculate that an increasing degree of economic insecurity and difficulty may contribute to rising ill-health, depression and even suicidal tendencies.

It’s a fact that economic inequality in the USA compares rather poorly with some other countries. There’s a World Bank measure, called the Gini coefficient: the higher it is, the more unequal is the country. The USA has a coefficient of 40.5; the Scandinavian countries range from 25.7- 27.7; in the UK it’s 34.8 (and the Brits worry about it). Some of the highest values are found in South America: Brazil has a coefficient of 53.9. The authors also point out that the mortality decline slowdown during the last 15 years compares with that recorded during the height of the AIDS epidemic in the USA, which claimed around 650000 lives. It’s a depressing picture: life is getting worse, not better, for a proportion of the American people. A disturbing finding in the richest country in the world.

[1] A Case and A Deaton (2015) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA vol 112 pages 15078-15083