Orgasm

Mind The Gap

A gap exists between male and female orgasmic capacity during intercourse. Why?

Posted November 15, 2013

Mind the gap

In sex, especially in casual hook-up sex, men orgasm more frequently than women. This has been referred to this as The Orgasm Gap. Various things have been proposed to explain it. Male laziness, and sexual ineptitude? A lack of female assertiveness about what they want? Is it that females are basically broken versions of males that are not designed to have orgasms anyway? This last idea has been championed by Elizabeth Lloyd in her 2005 book--largely based on a reading of Masters and Johnsons pioneering work which I have discussed elsewhere and don’t want to rehash here. However, what I do want to discuss is work that occurred at the same time but has not received the same coverage. At the same time that Masters and Johnson were measuring half a dozen people masturbating in a lab, and thereby concluding that female orgasm did nothing, there was another team in the UK investigating orgasm in rather a different way. This was the husband and wife team of the Foxes.

Insuck

Through using inserted radio telemetry devices the Fox team found that orgasm through intercourse generated internal pressure changes that could cause insuck (1) of sperm. The couple in question had been having sex together for ten years, knew each well, and were in their own bed. For all their pioneering zeal, Masters and Johnson may have neglected to appreciate that sterile laboratories are not places conducive to the full range of sexual response.

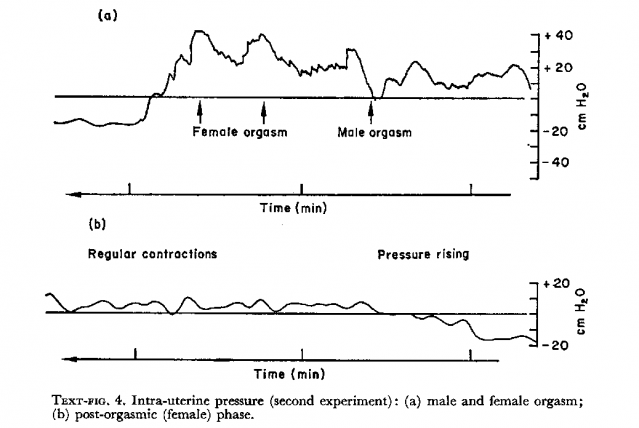

One of the relevant graphs about the pressure changes found by the Fox team is reproduced below. But, before you look at it, a quick quiz—and no peeking at the answer underneath. Can you tell--just by looking at the graph--why some of the most eminent scholars in the field have dismissed the Foxes findings as showing the exact opposite of what they claim they show?

Graph showing uterine pressure decrease following female orgasm (Fox, Wolff & Baker)

Did you spot it? The arrow showing the direction of time goes the opposite way from which you would expect. Normally, Time is depicted going from left to right in a graph. The Fox team showed time going right to left. A little ferreting around resulted in some of the most eminent scholars in my field confessing to me that they had been effectively holding the crucial graph (and a bunch of others) the wrong way up for the last twenty-odd years.

Peristaltic pumps

So, was this early series of studies just an isolated but heroic effort, doomed to lie, unreplicated? Not at all. The research programme started by the intrepid Fox team has been continued. Science moves on and techniques like hysterosalpingoscintigraphy, electrohysterography, and Doppler sonography that no-one knew about (or could even spell) in the 1970s have become available. Wildt et al’s (1998) team found—with a sample of fifty women this time-- that the system was a “peristaltic pump” that delivered sperm-like substances to the fertile follicle when stimulated by oxytocin—a known correlate of orgasm. Zervomanolakis et al (2007) found that this system increased fertility when functioning correctly. Now, oxytocin and orgasm are correlated but uterine contractions are one thing, orgasm is another (2). It could still be the case that the pleasurable effects of female orgasm signify nothing. So, if female orgasm occurs so irregularly, can it really be an adaptation?

Different kinds of adaptations

Some recent studies have treated female orgasm as an on/off capacity—you either have it or you don’t. As I have argued previously—this could be a mistake. Some traits are what is known as obligate--a good example would be height. Height doesn’t change in response to day to day environmental inputs--although your eventual height will be different depending on developmental inputs like nutrition. However, once you have the trait of being 6 feet tall this doesn’t change an awful lot. A facultative adaption is rather different—it’s an “if—then” trait. If X happens then Y follows. Skin tans in response to sunlight. No sunlight, skin forever pale. However, it would be a mistake to conclude that pale skin did not have the capacity to tan. A facultative adaptation “implies sensing and control mechanisms whereby the nature of the response can be adaptively adjusted to the ecological environment” (Williams, 1966, pp 81-82). Well, gee, that sounds like a romantic night out.

Non-random selection

If female orgasm occurred without pattern then perhaps we would be forced to agree that it has no function. But this is not the case. A predictable range of partner characteristics are correlated with female sexual response. I will go into detail about these in a longer blog post in the future but for the moment I just want to note one—partner smell. The women we interviewed frequently cited smell as an important partner characteristic that predicted orgasmic responses. Why is this important? Because smell conveys information about genetic compatibility. Many will now be aware of the famous smelly T-shirt experiments, where a shirt worn for a few days can be either disgusting or appealing to the opposite sex depending on how different the genes of the wearer are. Mixing genes means strong immune systems in a potential baby. But there is no point in a differential female sexual response unless there are a variety of partners to differentiate.

Try before you buy

For the sake of argument let’s accept that the multiple sensations and measurable effects of female orgasm are actually doing something useful. What drives them? There are various options for what female orgasm may be doing. One is the pair-bond hypothesis. In this view orgasm cements a bond with a potential father who will be needed to help care for a child. Another, somewhat opposed view, is the mate selection theory. This makes rather opposite predictions—namely that sex with high quality males will be especially likely to result in conception. Another possibility, much championed at the moment, is that female orgasm does nothing—existing only because of strong selection on males to have orgasms. I have argued at length elsewhere why I think that this view relies on anatomical naiveté. There is another possibility to consider—a sort of hybrid of the mate choice and pair bond hypotheses that makes somewhat different predictions to either of them. Sire choice.

Sire choice

Humans in love are the delight of all their friends. How we others—not so blessed by Cupid’s arrow at that present moment—adore hearing tales of how this particular special person is the sweetest, cuddliest, most wonderfulest example of humanity ever to have graced the earth with the tread of their foot. We (on the outside) are frequently agog at the fascinating stories of how this new paramour wrinkles their cute nose at certain cheeses or how they (too) think Godfather 3 is the best of the series. Humans are daffy about each other when they are in love. Oxytocin and dopamine do that to a human brain. Oxytocin, in particular, is generated through orgasm. During this daffy period—more technically referred to as a consortship by primatologists—any time not spent thrilling their friends with tales of their love-- the two primates in question are, err…consummating said love.

Lesbian bed death

This state of daffiness does not, alas, last forever. The sociologist Pepper Schwartz coined the term Lesbian Bed Death to refer to how same-sex female couples tend to have less and less sex the longer the relationship goes on. However, the same pattern is true of heterosexual partnerships as well. This discovery doesn’t deal a death blow to the pair-bond hypothesis—but it certainly needs explaining how a couple manages to stay together long after the hypothesised glue starts to lose its stickiness. Helen Fisher found that across the world the peak time for break-ups was five years—about enough time to grow a baby to viability. In another recent study it was found that after four years of marriage fewer than half of women desired regular sex. Recent sexual advice from a 98 year old woman—that to keep your marriage successful, one should treat it as an affair—would seem to back this up. Those that scoff at this advice might find that one person in the relationship has already taken it.

It’s not a bug, it’s a feature

In computing sometimes something appears to be malfunctioning when, in fact, it’s working just the way it was designed. The orgasm gap certainly exists. Men orgasm more than women during penetrative sexual intercourse. As I mentioned before--the number of male orgasms across the planet is 18000/second. Comparing this to the number of births (4.4/second) would seem to make male orgasm very inefficient at producing babies. Male orgasm is wanton, female orgasm is picky. This is despite the fact that women are not limited by physiology from orgasmsing. Many can do so multiple times—whereas the typical male has a refraction period of an hour or so.

Does this all go to show that female orgasm does nothing? Hardly. Lots of things about female sexuality is picky. Females are picky about partners, picky about when to have sex. Are they (unconsciously) picky about the times and places they orgasm? Probably. Are inept and uncaring males good choices to sire a baby? Probably not. These patterns can be measured.

Over to you

Our research team here at UCC is investigating these competing explanations. Building on previous work that found differential female response to different partner behaviours and traits we have devised a way to help decide which of the competing explanations is more likely to be true. We have piloted it and results are, in a preliminary way only, promising. We need participants. If you are interested then drop me a line and I will explain more details. It’s totally anonymous, and totally in the privacy of your own home. You will need to be female, and aged over 18. There is no upper limit on age—a spread of ages would be especially nice. Thanks in advance.

Fisher, H. E. (1994). Anatomy of love: A natural history of mating, marriage, and why we stray. Random House Digital, Inc.

Fox, C. A. (1976). Some aspects and implications of coital physiology. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 2, 205-213.

Fox, C. A., & Fox, B. (1971). A comparative study of coital physiology, with special reference to the sexual climax. Journal of Reproduction and Fertility, 24, 319-336.

Fox, C. A., Wolff, H. S., & Baker, J. A. (1970). Measurement of intra-vaginal and intra-uterine pressures during human coitus by radio-telemetry. Journal of Reproduction and Fertility, 22, 243-251

King, R., & Belsky, J. (2012). A typological approach to testing the evolutionary functions of human female orgasm. Archives of sexual behavior, 41(5), 1145-1160.

Klusmann, D. (2006). Sperm competition and female procurement of male resources. Human Nature, 17(3), 283-300.

Elizabeth, L. (2005). The case of the female orgasm: bias in the science of evolution.

Wallen, K., Myers, P. Z., & Lloyd, E. A. (2012). Zietsch & Santtila's study is not evidence against the by-product theory of female orgasm. Animal Behaviour.

Wildt, L., Kissler, S., Licht, P. & Becker, W. (1998). Sperm transport in the human female genital tract and its modulation by oxytocin as assessed by hysterosalpingoscintigraphy, hysterotonography, electrohysterography and Doppler sonography. Human Reproduction Update, 4, 655-666

Williams, G. C. (1966). Adaptation and natural selection. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Zervomanolakis, I., Ott, H. W., Hadziomerovic, D., Mattle, V., Seeber, B. E., Virgolini, I., Heute, D., Kissler, S., Leyendecker, G., & Wildt, L. (2007). Physiology of upward transport in the human female genital tract. Annals of the New York Academy of Science, 1101, 1-20.

Footnote 1 Insuck. The term used is insuck, not upsuck as you might have been led to believe. Very few scholars seem to have gone back and actually read the original work by the Fox team and the typo has therefore been propagated.

Footnote 2: It should be noted that one of the world’s leading anatomists believes that sperm is not transported more rapidly by female orgasm. Instead, Roy Levin argues that female orgasm causes cervical tenting which allows sperm to become more able to survive in the vaginal tract. He may be right. If he is—note that female orgasm is still performing a sperm-selection function. The ultimate function of orgasm—sperm selection—remains the same. If Levin is right then only the proximate mechanism is under dispute.