Relationships

How Romantic Love Originated in Metaphysics and Cosmology

The early beginnings of the concept of romantic love.

Posted April 14, 2023 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- The early philosopher Empedocles held that there are four primary elements, which are governed by two causal principles, love and strife.

- These notions influenced Plato’s Myth of Aristophanes, on the origins of love.

- In turn, Plato and the Myth of Aristophanes played an important part in the development of the modern notion of romantic love.

The pre-Socratic philosopher Empedocles (d. c. 434 BCE) hailed from Acragas, now Agrigento, in Italy. He had a reputation as a mystic and miracle worker and claimed to be able to cure old age and control the winds. When offered the kingship of Acragas, he turned it down, preferring instead to write poetry and dedicate it to his beloved, the physician Pausanias. He is, in fact, the last Greek philosopher to have expressed his ideas in verse. About 550 lines survive, including 450 lines of his On Nature.

Empedocles synthesized the thought of earlier philosophers by holding that there are four “roots," or primary substances: air, earth, fire, and water—now referred to as the four classical elements. The four roots are driven together and apart, and combine in various proportions to create the plurality and difference of sense experience. They are like a painter’s primary colours, from which the artist can reproduce all the varied and variable splendours of nature. The four roots of Empedocles inspired or influenced the four-humour theory of medicine.

In addition to the four roots, Empedocles introduced not one but two causal principles: love and strife. Love brings the elements together, and unopposed love leads to “the One," a divine and resplendent sphere. But strife gradually degrades this sphere, returning it to the elements, and this cosmic cycle repeats itself for all time.

Like Pythagoras (d. c. 495 BCE), Empedocles believed in metempsychosis, that is, in the transmigration of the soul at death into a new body of the same or a different species, until such a time as it became moral. Souls can help themselves by abiding by certain ethical rules, such as refraining from meat, beans, bay leaves, and (heterosexual) intercourse. Animals and even certain plants are our kin and should not be killed for food or sacrifice. Empedocles and Pythagoras were pacifists and vegans long before the hippies came around. Their mortification of the flesh is, in some sense, the apotheosis of the pre-Socratic privileging of Apollonian reason over Dionysian sense experience.

Empedocles himself claimed to have already been a bush, a bird, and “a mute fish in the sea." But now, as a doctor, poet, seer, and leader of men, he had reached the highest rung in the cycle of incarnations—and could, just about, count himself among the immortal gods.

In a story that is almost certainly false but too good not to tell, he killed himself by leaping into the flames of Mount Etna, either to prove that he was immortal or make people believe that he was.

Plato’s Myth of Aristophanes

The premise of Plato’s Symposium [Banquet] is that each of the guests at the banquet is to deliver a speech in praise of love. The playwright Aristophanes, however, chooses to deliver his speech in the form of a myth about the origins of love. This is the famous Myth of Aristophanes, which appears to lean upon elements of the cosmology of Empedocles.

In the beginning, there were three kinds of people: male, descended from the sun; female, descended from the earth; and hermaphrodite, with both male and female parts, descended from the moon.

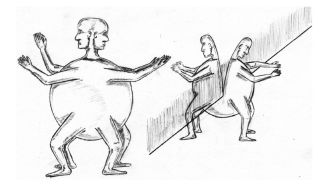

These early people were completely round, each with four arms and four legs, two identical faces on opposite sides of a head with four ears, and all else to match. They walked both forward and backward and ran by turning cartwheels on their eight limbs, moving in circles like their parents, the planets.

Because they were wild and unruly and threatening to scale the heavens, Zeus, the father of the gods, cut each one down the middle "like a sorb-apple which is halved for pickling"—and even threatened to do the same again so that they might hop on one leg.

Apollo, the god of light and enlightenment, then turned their heads to make them face towards their wound, pulled their skin around to cover up the wound, and tied it together at the navel like a purse. He made sure to leave a few wrinkles on what became known as the abdomen so that they might be reminded of their punishment.

After that, people searched all over for their other half. When they finally found it, they wrapped themselves around it so tightly and unremittingly that they began to die from hunger and neglect. Taking pity on them, Zeus moved their genitals to the front so that those who were previously androgynous could procreate, and those who were previously male could obtain satisfaction and move on to higher things.

This is the origin of our desire for others: Those of us who desire members of the opposite sex used to be hermaphrodites, whereas men who desire men used to be male, and women who desire women used to be female. When we find our other half, we are “lost in an amazement of love and friendship and intimacy” that cannot be accounted for by mere lust, but by the need to be whole again, to be restored to our original nature. Our greatest wish, if we could only have it, would then be for Hephaestus, the god of fire, to melt us into one another so that our souls could be at one and share in a common fate.

The Myth of Aristophanes, and so Empedocles, came to play an important part in the development of the modern, romantic notion of love as existential and redeeming, and a fit substitute for the dying love of God.

Neel Burton is the author of The Gang of Three: Socrates, Plato, Aristotle.