Anxiety

Can Anxiety Be Good for Us?

If so, when does anxiety become a problem?

Updated June 23, 2024

On October 30, 1938, Orson Welles broadcast an episode of the radio drama Mercury Theatre on the Air. This episode, entitled The War of the Worlds and based on a novel by HG Wells, suggested to listeners that a Martian invasion was under way.

In the charged atmosphere of the days leading up to World War II, many missed or ignored the opening credits and mistook the radio drama for a news broadcast. Panic ensued and people began to flee, with some even reporting flashes of light and a smell of poison gas.

This panic, a form of mass hysteria, is one of the many forms that anxiety can take. But what is anxiety, what purpose does it serve, and when can it become a problem?

Definition of anxiety

Anxiety can be defined, very broadly, as ‘a state consisting of psychological and physical symptoms brought about by a sense of apprehension at a perceived threat’. Fear is similar to anxiety except that with fear the threat is, or is perceived to be, more concrete, present, or imminent.

Symptoms of anxiety

The psychological and physical symptoms of anxiety vary according to the nature and size of the perceived threat, and from one person to another. Psychological symptoms may include feelings of fear and dread, an exaggerated startle reflex, poor concentration, irritability, and insomnia.

In mild to moderate anxiety, physical symptoms such as tremor, sweating, muscle tension, a faster heart rate (tachycardia), and faster breathing (tachypnoea) arise from the body’s fight-or-flight response, a state of high arousal fuelled by a surge in adrenaline. Some people can also develop a dry mouth and the feeling of a lump in the throat. This lump feeling, referred to as globus hystericus, is associated with forced swallowing and a gulping sound that is often exploited in cartoons to signal fear.

In severe anxiety, hyperventilation, or over-breathing, can lead to a fall in the concentration of carbon dioxide in the blood. This gives rise to an additional set of physical symptoms, among which chest discomfort, numbness or tingling in the hands and feet, dizziness, and faintness.

Uses of anxiety

Fear and anxiety can be a normal response to life experiences, protective mechanisms that have evolved to prevent us from entering into potentially dangerous situations, and to help us escape should they befall us regardless. For example, anxiety can prevent us from coming into close contact with pestilent or venomous animals such as rats, snakes, and spiders; from engaging with a much stronger or angrier enemy; and even from declaring our undying love to someone who is unlikely to return or spare our feelings.

If we do find ourselves caught in a threatening situation, the fight-or-flight response triggered by fear can help us to mount a suitable response by priming our body for action and increasing our performance and stamina.

In short, the purpose of fear and anxiety is to protect us from harm and, above all, to preserve us from death—whether literal or figurative, biological or psychosocial.

The Yerkes-Dodson curve

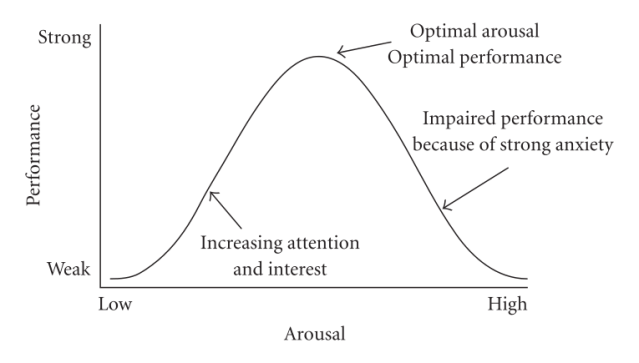

Although some degree of anxiety can improve our performance on a range of tasks, severe or inappropriate anxiety can have the opposite effect and impair our performance. Thus, whereas a seasoned actor may perform optimally before a live audience, a novice may suffer from stage fright and freeze.

The relationship between performance and anxiety can be expressed graphically by a parabola or inverted ‘U’.

According to this Yerkes-Dodson curve, our performance increases with arousal but only up to a certain point, beyond which it starts to decline. The Yerkes-Dodson curve best applies to complex or difficult tasks rather than simple tasks for which the relationship between arousal and performance is more linear. Also important is the nature of the task. Generally speaking, cerebral challenges require a lower level of arousal for optimal performance than tasks that call for strength and stamina. This makes good sense, since those situations that trigger the greatest anxiety are generally those that call for the greatest strength and stamina, for instance, to fend off a predator or scamper up the nearest tree.

In closing

The Yerkes-Dodson curve indicates that very high levels of anxiety can result in handicap, even paralysis. From a medical standpoint, anxiety becomes pathological when it becomes so severe, frequent, or longstanding as to prevent us from doing the sorts of things that most people take for granted, such as leaving the house or even just our bedroom. I once treated a patient with a severe anxiety disorder who, to avoid crossing the corridor from bedroom to bathroom, urinated into a bottle and defaecated into a plastic bag.

Pathological anxiety often owes to a primary anxiety disorder, although in some instances the anxiety is secondary to another psychiatric disorder such as depression or schizophrenia, or to a medical disorder such as hyperthyroidism or alcohol withdrawal.

Primary anxiety disorders are increasingly common, now affecting as many as one in five Americans in any given year. They commonly present in one or more patterns such as a phobic anxiety disorder, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, a conversion disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or a culture-bound syndrome.

Like the adaptive forms, these pathological forms of anxiety are readily interpreted in terms of life and death.

Read more in The Meaning of Madness.