Health

Is an Illness Ever 'All in the Mind'?

Somatization, factitious disorders, malingering, and psychoneuroimmunology.

Posted April 12, 2012

[Updated on 7 September 2017]

Whereas displacement (see my previous post, The Games People Play) involves the redirection of psychological distress towards someone or something less threatening, somatization involves its transformation or conversion into more tolerable physical symptoms. This could involve a loss of motor function in a particular group of muscles, resulting, say, in the paralysis of a limb or a side of the body (hemiplegia). Such a loss of motor function may be accompanied by a corresponding loss of sensory function. In some cases, sensory loss might be the presenting problem, particularly if it is independent of a motor loss or if it involves one of the special senses such as sight or smell. In other cases, the psychological distress could be converted into an unusual pattern of motor activity such as a tic or even a seizure (sometimes called a ‘pseudoseizure’ to differentiate it from seizures that have a physical basis such as epilepsy or a brain tumour). Pseudoseizures can be very difficult to distinguish from organic seizures. One method of telling them apart is to take a blood sample 10-20 minutes after the event and to measure the serum level of the hormone prolactin, which tends to be raised by an organic seizure but unaffected by a pseudoseizure. More invasive but also more reliable is video telemetry, which involves continuous monitoring over several days with both a video camera and an electroencephalograph[1].

Given that all these different types (and there are many more) of somatized symptoms are psychological in origin, are they any less ‘real’? It is quite common for the person with somatized symptoms to deny the impact of any traumatic event and even to display a striking lack of concern for his disability (a phenomenon referred to in the psychiatric jargon as la belle indifférence), thereby reinforcing any forming impression that the somatized symptoms are not ‘genuine’. However, it should be remembered that ego defences are by definition subconscious, and that the somatizing person is therefore not conscious or, at least, not entirely conscious, of the psychological origins of his physical symptoms. To him, the symptoms are entirely real, and they are also entirely real in the important sense that—despite their apparent lack of a biological basis—they do in fact exist, that is, the limb cannot move, the eye cannot see, and so on[2]. For these reasons, some authorities advocate replacing terms such as ‘pseudoseizures’ and the even older ‘hysterical seizures’ with less judgmental terms such as ‘psychogenic non-epileptic seizures’ that do not inherently imply that the somatized symptoms are in some sense false or fraudulent.

Factitious disorders and malingering

It is very common, particularly in traditional societies, for people with what may be construed as depression to present not with psychological complaints but with physical complaints such as fatigue, headache, or chest pain; like many ego defences, this tendency to concretize psychic pain is deeply ingrained in our human nature, and should not be mistaken or misunderstood for a factitious disorder or malingering.

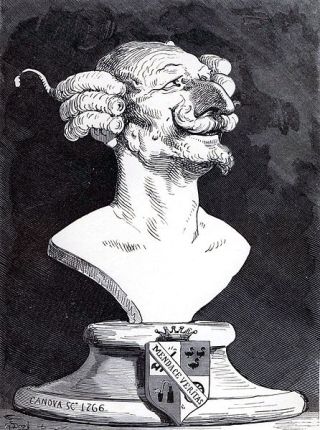

A factitious disorder is defined by physical and psychological symptoms that are manufactured or exaggerated for the purpose of benefitting from the rights associated with the ‘sick role’[3], in particular, to attract attention and sympathy, to be exempted from normal social roles, and, at the same time, to be absolved from any blame for the sickness. A factitious disorder with predominantly physical symptoms is sometimes called Münchausen Syndrome, after the 18th century Prussian cavalry officer Baron Münchausen. The Baron was one of the greatest liars in recorded history, and one of the most notorious of his many ‘hair-raising’ claims was to have pulled himself out of a swamp by the very hair on his head.

Whereas a factitious disorder is defined by symptoms that are manufactured or exaggerated for the purpose of enjoying the privileges of the sick role, malingering is defined by symptoms that are manufactured or exaggerated for a purpose other than enjoying the privileges of the sick role. This purpose is usually much more concrete and immediate than that of a factitious disorder, for example, claiming compensation, evading the police or criminal justice system, or obtaining a bed for the night. Thus, it is quite clear that somatization has little to do with factitious disorders or malingering; although a person with somatization (as, indeed, most any ill person) may enjoy the privileges of the sick role and may receive material benefits as a result of being ill, neither is his primary purpose.

Psychoneuroimmunology

In recent decades, it has become increasingly clear that psychological stressors can lead to physical symptoms not only by the ego defence of somatization but also by physical processes involving the nervous, endocrine, and immune systems. For example, one recent study conducted by Dr Elizabeth Mostofsky of Harvard Medical School found that the first 24 hours of bereavement are associated with a staggering 21-fold increased risk of a heart attack. Since Robert Ader’s initial experiments on lab rats in the 1970s, the field of psychoneuroimmunology has truly blossomed. The large and ever increasing body of evidence that it continues to uncover has led to the mainstream recognition not only of the adverse effects of psychological stress on health, recovery, and ageing, but also of the beneficial effects of positive emotions such as happiness, motivation, and a sense of purpose. Here again, modern science has barely caught up with the wisdom of the Ancients, who were well aware of the strong link between psychological wellbeing and good health.

Neel Burton is author of The Meaning of Madness, The Art of Failure: The Anti Self-Help Guide, Hide and Seek: The Psychology of Self-Deception, and other books.

Find Neel Burton on Twitter and Facebook

[1] An apparatus that records electrical activity along the skull.

[2] Similarly, the headaches that I get whenever I end up doing something that I should not be doing (usually involving making money) are very real. Over time, I have learnt to listen to these headaches, and am very much poorer for it.

[3] Talcott Parsons, 1951.