Child Development

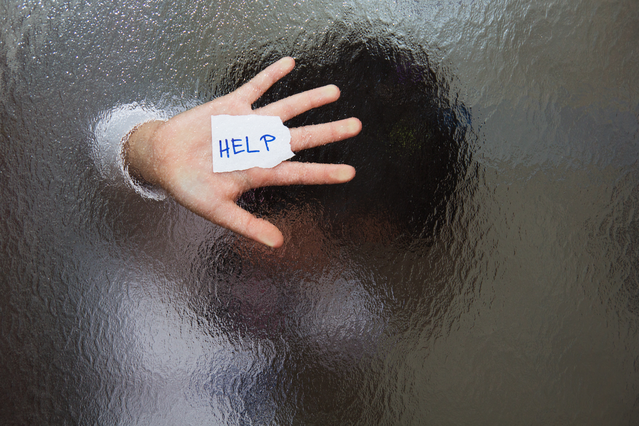

Why Asking for Help Is Hard to Do

Find your path toward greater self-actualization and empowerment.

Posted April 5, 2017 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Despite the fact that we’ve come a long way regarding the de-stigmatization of therapy, it still seems as if reaching out and asking for professional help is the last option for millions of people. There’s a list of strategies that come before therapy:

- Talking to friends and family

- Connecting with clergy

- Reading self-help books

- Watching talk shows that offer quick fixes for whatever ails you

- Surfing the Internet for diagnoses and answers

- Posting vulnerable questions anonymously in chat rooms and hoping for guidance.

It’s not that those aren’t good resources, and sometimes they can be very helpful and an important first step. But many people wait for everything else to fall apart before contacting a therapist.

I believe it takes tremendous courage to reach out to a mental health professional. I understand the brave vulnerability that’s created when someone decides to disclose to a relative stranger their important and intimate thoughts, feelings, and experiences. It’s always poignant to sit with new clients and hear them distort coming into therapy—something that takes great inner strength—as a “weakness” or “failure.” Why would they think asking for help is a sign of weakness? And why is it so hard to ask in the first place?

Like many other things, I believe this has its roots in family-of-origin experiences. If asking for help is hard for you, take some time to consider the following:

- While you were growing up what kind of messages did you get about asking for help?

- Did your family place more value on “doing it yourself” or “letting others in?”

- When you did attempt to reach out in childhood, how did the people in your life respond?

Those few questions can shed a lot of light on whether you go through life overly self-reliant or feel comfortable turning to others for guidance, feedback, support, or comfort. If the messages you got, overtly or covertly, taught you that reaching out was unacceptable, futile, or would cause more pain, it makes sense that you would go it alone whenever possible. Through their own actions, family members modeled whether or not asking for help was acceptable. They also taught you the extent to which outsiders could be trusted resources.

And most importantly, your past experiences with family, teachers, peers, and other significant people in your life served to either reinforce the notion that help was available, consistent, predictable, and safe, or left you with the painful impression that your needs would go unheard and unanswered. In those cases, it probably felt less depressing and rejecting to simply stop asking for help than to ask and not get a supportive response.

Although these formative experiences go a long way towards helping you understand why asking for help might continue to be a challenge, consider the fact that you don't need to keep superimposing past events onto the present. It's never too late to learn to ask for help and re-frame it as a sign of strength.

When you’re faced with feelings or experiences that are challenging, frightening, or overwhelming, asking for help means you care enough about yourself to increase the likelihood that things will work out in your favor by getting the support you deserve. Learning how to be selective when you reach out can also increase your chances of getting a safe and compassionate response.

Think about these questions as you take the first brave steps towards asking for help when you need it:

- What are the situations in your life that would benefit from outside help and support?

- Who are the people in your life who would be safe to reach out to for assistance?

- What professional resources would you encourage a best friend to use if they needed help?

- What are three ways in which asking for professional help can be a sign of strength?

Lisa Ferentz, LCSW-C, is the author of Finding Your Ruby Slippers: Transformative Life Lessons From the Therapist’s Couch.