Chronic Pain

How Tattletale Nerves Cause Chronic Pain

The connection between stress, the nervous system, and chronic pain.

Posted September 29, 2023 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Central sensitization syndromes share the feature of nerve sensitization.

- Sensitization causes nerves to be overreactive and contributes to a variety of chronic pain disorders.

- Unrelenting stress is a common trigger for sensitization syndromes. Symptoms also worsen or flare with stress.

There is a good chance you know someone with a central sensitization syndrome. Someone with chronic migraines for years? Someone with chronic back pain for years? Someone with chronic digestive symptoms for years? Years of severe symptoms without an adequate explanation? These are all potential cases of sensitization.

Central sensitization syndromes (CSS) are a group of medical conditions that share the common abnormality of nerve sensitization. They affect as many as 30 million adults in the United States. Examples include chronic migraine, back pain, bladder pain, pelvic pain, and irritable bowel syndrome. The individual conditions differ in many ways but all share the feature of over-reactive nerves (sensitization).

High stress is one trigger for sensitization syndromes. The symptoms also worsen or flare with stress. Everyone’s body is a little different and communicates with them in its own way. Some people develop headaches and some get stomach aches, while others experience flares of pain in the back.

Common sensitization syndromes

- Chronic back pain and neck pain

- Chronic muscle pain (myofascial pain syndrome)

- Fibromyalgia

- Temporomandibular joint disorder

- Chronic heartburn or stomach pain

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Migraine headaches

- Chronic tension-type headaches

- Chronic bladder pain (i.e., interstitial cystitis)

- Chronic pelvic pain

How sensitization creates misery

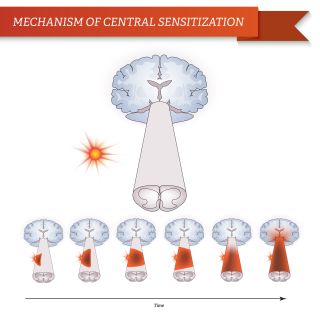

Nerve sensitization arises from abnormalities in how pain signals are processed and perceived in the brain, spinal cord, and nerves. Sensitization makes the nerves more sensitive and more reactive to stimuli which increases pain levels. There is increased reactivity to normal sensory inputs, such as touch and movement.

Sensitized nerves exaggerate the pain signal when reporting it to the brain. The reactive nerves send more pain signals, more often. They are like tattletales, constantly telling the brain something is wrong. The person then perceives something serious is wrong. It’s what I call a “maladaptive biologic process." The nerves get confused and adjust in an unhelpful way; the brain believes the tattletale nerves.

When sensitization is present, it changes how you experience pain. You feel it more easily, more intensely, and in more places.

Here are the three ways that sensitization exaggerates pain levels.

1. Pain hypersensitivity is increased sensitivity to sensory inputs, such as touch, pressure, and movement. Let's consider two people, one with sensitization and the other without it. They both lift a 50-pound box and feel a pull in the back. The person without sensitization reports the pain as a “three out of ten.” Meanwhile, the person with sensitization reports the pain as a “seven out of ten." The nerves are telling the brain it hurts more than what a person without the condition feels. It’s not the person overreacting; the intensity is very real. The sensation is because the nerves are hypersensitive.

2. Pain in response to things that aren’t normally painful. Light pressure on the back muscles shouldn’t cause discomfort outside of an injury. With nerve sensitization, a mild touch can prompt a substantial pain response. And, after being touched, there can be unpleasant sensations, like burning or tingling.

3. The pain spreads to more parts of the body. With sensitization, pain spreads beyond the injured area, such as the joint or nerve. One example is with back pain. Instead of a small area of the back hurting, a person with nerve sensitization may feel pain across the back and down into the thighs. Another example is with nerves, someone with a pinched nerve may feel their entire leg is numb, instead of just the area supplied by the irritated nerve.

Non-pain symptoms still hurt

In addition to affecting how pain is experienced, sensitization causes symptoms that affect the entire body. Called “non-pain symptoms," these include activity-limiting fatigue, disrupted sleep, and thinking difficulties. Tattletale nerves throw the entire nervous system off.

The fatigue can be severe with a much lower energy level compared to others of the same age and health. Fatigue sets in much sooner and recovery lasts longer. For example, after an hour of intense exercise, someone with sensitization may need to rest for the remainder of the day or two days.

Sleep issues range from frequently waking up at night to feeling tired and unrefreshed in the morning. Compounding the struggle, poor sleep increases pain sensitivity and worsens fatigue.

Brain fog is another issue. With brain fog, the mind feels muddled and slow. Memory is poor and it’s hard to concentrate. You get to work and try focusing on your task list but it takes forever because you can’t think clearly.

The environment is full of sensory inputs and nerve sensitization magnifies these stimuli, too. The impact of harsh lights, loud noise, and odors is amplified. These stimuli may provoke headaches, nausea, or dizziness.

Taken together, the symptoms cause fatigue and disrupted sleep which limits activities. Then brain fog makes it harder to get through the activities. Now add sensitivity to light and noise, and smells that make you uncomfortable. Combined, the non-pain symptoms may limit you more than the pain.

A system-wide problem

Between the pain condition—such as headaches or back pain—and the non-pain symptoms, nerve sensitization affects the function of the entire body. Your brain and nervous system are in charge of helping you think clearly, be active, and regulate sleep. If that system is not working normally, all of its functions are affected. With sensitization syndromes, the disorder does not stem from just the back or head or stomach, but from the entire nervous system.

Central sensitization syndromes are the most frequent type of stress-related disorder I encounter. When people don’t respond to standard therapy—like physical therapy or anti-inflammatory medications—stress or sensitization is the missing piece that needs to be addressed. If sensitization is the main driver of symptoms, the treatment requires a different approach.

References

Muhammad B. Yunus, “Editorial Review (Thematic Issue: An Update on Central Sensitivity Syndromes and the Issues of Nosology and Psychobiology),” Current Rheumatology Reviews 11, no. 2 (July 2015): 70–85.

Jo Nijs et al., “Nociplastic Pain Criteria or Recognition of Central Sensitization? Pain Phenotyping in the Past, Present and Future,” Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 15 (July 21, 2021): 3203.