Suicide

Why Did Teen Suicides Increase Sharply from 1950 to 1990?

What changes over this four-decade period led ever more boys to kill themselves?

Posted September 18, 2023 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

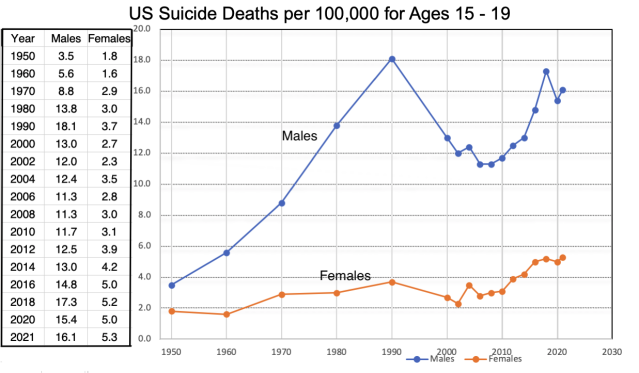

In my last post I presented a table and a hand-drawn graph showing changes in the suicide rate for U.S. teenagers, separately for boys and girls, from 1950 through 2021. Here—with thanks to my colleague Tony Christopher (executive director of the National Institute for Play)—I present a more polished version of the graph along with the table.

In that post I asked readers to suggest—-on a separate platform that allows comments (here)—any hypotheses they might have regarding causes of the major shifts in suicide rate, especially for boys, shown in the graph. More specifically, what might have accounted for (1) the sharp, essentially linear increase in suicides from 1950 to 1990, (2) the sharp decline from 1990 to 2002, and (3) the sharp increase, again, beginning about 2010?

My request elicited many thoughtful comments, with quite plausible suggestions. In this post I take those ideas into account to discuss theories about the first of the three questions—that about the huge rise in suicides for boys (and smaller rise for girls) between 1950 and 1990. I’ll discuss ideas pertaining to the second and third questions in posts to follow this one.

But first, it seems necessary to comment on the obvious huge difference between boys and girls in suicide rate, which is present no matter what year we are looking at.

Why Do Boys Commit Suicide Much More Often than Girls?

A large sex difference in suicide rate is found not just for teens, but also for people of all ages. Generally, it is reported that girls and women attempt suicide more than do boys and men, but boys and men complete it more. To this I should note that suicide experts acknowledge that the label “attempted suicide” can be misleading. If a person “attempts suicide” but doesn’t die, was it an actual suicide attempt or was it a cry for help, a dramatic message saying, essentially, “I can’t go on unless something changes here.”

As some suicide researchers have pointed out, it is not difficult to kill yourself if you really want to. A gunshot, or hanging, or a high enough dose of a poison taken in some place where nobody will find you soon will do it. Guns and hanging are the most common means of completed suicides. In contrast, a not-too-high dose of poison, taken where others will soon be, is the most common means of “attempted suicide.”

The sex difference in suicide rate is not, apparently, the result of sex differences in anxiety, depression, or feelings of hopelessness. On questionnaires, girls and women consistently report these feelings at higher rates than do boys and men.

One theory of the difference is that boys and men may have more ready access to guns than do girls and women, and gunshot is the quickest, most certain way of ending your life. Consistent with the gun theory, in 2020 (a year for which I found data here) guns were used in 58% of completed suicides by boys and young men but only by 29% of those by girls and young women. For girls and young women, suffocation (usually by hanging) was the most common means (42%), and poison was relatively common (16% for females compared to 3% for males).

Another, perhaps more compelling theory, is the impulsivity theory. On average, males are more impulsive than are females, and this may be especially true for teens. That’s why boys are much more frequently diagnosed with ADHD (which is fundamentally high impulsivity) than are girls, and it helps explain why boys, often without much thought, do risky things more frequently than do girls.

With admitted oversimplification, we might think of it this way. A male suffers some serious negative experience that leads him to think about ending his life, and he impulsively acts on it (especially if there is a gun in the house). A female suffers some serious negative experience that leads her to think about ending her life, but (even if there is a gun in the house) doesn’t impulsively do it. She mulls it over. Maybe she talks about it with a relative or friend. Maybe she seeks counseling. Or maybe she dramatically announces her need for something to change by taking enough pills to look like a suicide attempt. She doesn’t die. Consistent with the impulsivity theory, the rate of suicide among both boys and girls diagnosed with ADHD is much higher than it is for those without that diagnosis (Garas & Balazs, 2020).

The just-preceding paragraph also supports another theory about the sex difference, which we might call the self-reliance theory. Girls and women are, on average, more willing to ask for help when they have emotional needs than are boys and men. Whether by biology or culture (most likely both), boys and men are more inclined than are girls and women to think they should be able to solve their own problems, even if the only solution they can think of is suicide.

I suspect that all these theories are to some degree true. Combined, they may account for the large sex difference in completed suicides.

What Caused the Huge Increase in Suicides (Especially for Boys) Between 1950 and 1990?

Now, to the main point of this post. Here are some theories about why teen suicide rates increased so dramatically and consistently from 1950 to 1990. I start with the theory that I think has by far the greatest weight of evidence.

The constraints on independence theory

I have long been contending, with much evidence, that the primary cause of the huge, almost linear increase in suicides over four decades was a continuous decline in the freedom of children and teens to do what they must do to be happy and to develop the character traits (such as courage) required to deal with the bumps in the road of life (Gray, 2011, 2013; Gray, Lancy, & Bjorklund, 2023).

Historical research, reports by social scientists over the years, analyses of advice-to-parents articles in popular magazines—as well as my own lived experience—make it clear that children and teens in the mid-20th century and earlier had far more freedom to play, roam, explore, socialize, take risks, contribute meaningfully to their community, and do all the things that make young people happy and help them develop the character traits that promote resilience than they do today (Gray, Lancy, & Bjorklund, 2023). Freedoms were not just suddenly taken away; they were gradually taken away. Because it occurred gradually, many people did not notice the change, or if they did, they thought of it as small because the year-to-year change was small. But over that whole 40-year period, it was huge.

In our recent Journal of Pediatrics article (also summarized here), anthropologist David Lancy, developmental psychologist David Bjorklund, and I summarize multiple, converging lines of evidence and logic supporting the idea that a continuous decline in freedom to engage in independent activities—activities not directly controlled and supervised by adults—was a major cause of the continuous decline in mental health among young people. As you will see in either of these sources, there is evidence that the trend toward ever more restrictions on young people’s independence has continued since 1990, but for the now I’m concerned only with 1950-1990. Something else happened around 1990 that brought the suicide rate down for a while, but that’s a story for my next post.

I’m tempted to call this theory of the rise of suicide the imprisonment theory, because over these decades children and teens were increasingly imprisoned in school and at home. But, to avoid sounding as angry as I truly am about what we have done to kids, I’m calling it the constraints on independent activity theory.

Although both boys and girls would suffer from the decline in freedom, one might plausibly argue that boys on average would be more affected than girls. In an insightful comment on my previous post, Linda Hagge wrote (and I quote with her permission):

“My hunch would be that since WW2 there has been a gradual restriction of freedom for boys. Greater urbanization, more eyes on them, less time outside, etc. We have denied their evolutionary imperative to gather in packs during their teen years and roam around being annoying and getting into trouble--that period in a boy's life is formative. What we think is a civilizing influence may be backfiring.”

Yes! I was a WW2 baby and have lived the period we are talking about. That’s exactly what happened. I would be remiss, however, not to mention some other plausible contributors to the increase in suicides suggested by readers.

The change in death recording theory

One reader suggested that a change in how deaths are officially recorded might have affected the number of deaths attributed to suicide. Maybe there was more stigma about suicide in earlier years, so, to please families, suicides were more likely, then, to be recorded officially as accidents. That is plausible, but there are two arguments against it as a major cause of the change.

First, the huge increase in suicides over this period occurs only for teens and young adults (age 20 to 24). For adults ages 25 to 65, the rate of suicide for both sexes remained relatively flat over this period, and, for those over 65, it decreased significantly. So, the recording theory works only if you assume the motivation to fudge the record applied only to youth suicides and not to beloved spouses, parents, and grandparents.

The other argument against it is that it would be hard to attribute death by hanging to an accident, so the death-recording theory would have to focus on deaths by gunshot, which might plausibly be attributed to accident. But, if gun suicides were more often recorded as gun accidents in earlier decades, then we should see relatively more deaths by gun accidents in those decades, but the records show no such shift in the rates of death by accidental self-shooting (Cutler et al., 2001).

The guns in home theory

According to this theory, since most suicides are with guns, increased access to guns could be a cause. There is indeed evidence that teens living in homes where there is a gun are about four times as likely to commit suicide as those living in gun-less homes (Cutler et al., 2001). (A gun at home also increases the likelihood of all other gun-related deaths to family members, including gun accidents and murders, which should give pause to anyone who thinks it’s a good idea to keep a gun at home.)

However, the percentage of households in the United States with at least one gun did not increase, and in fact declined, over the years we are considering. According to one report (here), for example, household gun ownership declined gradually, from about 50% of homes in 1973 to about 30% in 2000. So, support for the guns-at-home theory seems to be lacking.

The decline in religious affiliation theory

One reader made the very reasonable suggestion that a decline in church attendance may be a cause. There is indeed evidence that people who attend church are on average happier than those who don’t, but that may have more to do with the social aspect of church attendance than religiosity. In general, the more socially involved people are, the happier they are. Church attendance and other regular social occasions may bring people together and increase friendships, connectedness, and social support, which would reduce depression and suicide.

According to a systematic review of research on religiosity and suicide, however, there is only weak and inconsistent evidence that religious affiliation protects against suicide (Lawrence et al, 2016). Moreover, there is evidence that gays and lesbians (who account for a disproportionate number of suicides) are more likely to kill themselves if they have fundamentalist religious beliefs or come from a fundamentalist family than otherwise, for reasons that are probably obvious (Lytle, 2018). They may believe they have sinned against God, or their family members may believe that and reject them.

The change in family structure theory

Another reasonable suggestion from a reader is that change over time in family structure may have caused an increase in teen suicide. There is indeed evidence that teens whose parents have divorced have a somewhat elevated risk for suicide (Cutler et al, 2001), but I know of no evidence that their risk is any greater than that of teens living in a two-parent family where one parent is consistently abusive to the other (which was more common before divorce became easier). Moreover, the divorce rate peaked in 1979 and declined gradually after that (here), but the suicide rate for teens continued to increase.

The percentage of single-parent families did increase over the period we are talking about, but there is little evidence that teens in single-parent homes commit suicide at a greater rate than those in two-parent homes (Cutler et al, 2001). Moreover, even though a higher percentage of Black families than White families were headed by a single parent over this period, the suicide rate among Black teens was consistently lower than the rate among White teens over these decades. There is, however, some evidence for a correlation between teen suicide rate and the amount of time parents spend outside the home at work (Cutler et al, 2001), and two-parent participation in the workforce did increase over the period under discussion.

Conclusion and Final Thoughts

My conclusion from the research described here is that constraints on teens’ independence is by far the leading cause of the increased rate of teen suicides between 1950 and 1990, but there is reason to think that other factors—perhaps especially the decline in parental presence at home—may have contributed to some degree.

As I said at the beginning, I have long been convinced that the major cause of the rise in anxiety, depression, and suicide among teens after 1950 is the ever-increasing constraints on their freedom to play, roam, associate freely with peers, and in other ways engage themselves in the real word. However, this is the first time I have given serious consideration to ideas about other social changes after 1950 that could have contributed to the increasing suicide rate. I thank those who commented on the previous post for suggesting ideas to think about. I am now even more convinced than before that decline in freedom is the primary cause.

The biggest puzzle in the teen suicide graph, which I have not yet addressed, is this: What caused the sudden drop in suicides from 1990 to 2002, followed by a leveling off from 2002 to 2010 before rising again? I must admit that in my previous writings I have generally ignored this puzzle and focused on the pattern of increased distress and suicides that was clearly present both before 1990 and after 2010. I was content to see the temporary decline as an unexplained anomaly, a blip in the overall chart of continuous decline in young people’s mental well-being. But my contentment has now vanished.

Anomaly it may be, but it’s much too big to be just random variation. Anomalies this big have causes. Something had to change beginning about 1990. What was that? In my next post I will present my current thinking about that. I have a couple of theories that may surprise you.

As always, I welcome your thoughts and questions. Psychology Today does not allow comments, so I have posted this on a different platform where you can comment. I invite you to comment here.

References

Cutler, D.M., Glaeser, E.L., & Norberg, K.E. (2001). Explaining the rise in youth suicide. Ch 5 in J. Gruber (ed.) Risky behavior among youths: An economic analysis. University of Chicago Press. 2001. (Out of print but available at https://www.nber.org/books-and-chapters/risky-behavior-among-youths-economic-analysis)

Garas, P., & Balazs, J. (2020). Long-term suicide risk of children and adolescents with attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder—a systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 11. Article 557909.

Gray, P. (2011). The decline of play and the rise of psychopathology in childhood and adolescence. American Journal of Play, 3, 443-463.

Gray, P. (2013). Free to learn: why unleashing the instinct to play will make our children happier, more self-reliant, and better students for life. Basic Books.

Gray, P., Lancy, D.F., & Bjorklund, D.F. (2023). Decline in independent activity as a cause of decline in children’s mental wellbeing: summary of the evidence. Journal of Pediatrics 260, 1-8. 2023. Available here.

Lawrence, R.E., Oquendo, M.A., & Stanley, B. (2016). Religion and suicide risk: A systematic review. Archives of Suicide Research, 20, 1-21.

Lytle, M.C., Blosnich, J.R., De Luca, S.M., & Brownson, C. (2018). Association of religiosity with sexual minority suicide ideation and attempt. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 54 (#5), 644-651.