ADHD

Is ADHD a Real Disorder or One End of a Normal Continuum?

Rethinking ADHD as a common set of traits and an evolutionary mismatch.

Posted January 6, 2021 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

As a psychiatrist, I’ve been reflecting a lot lately on how, over a span of many years, I went from only occasionally diagnosing ADHD to seeing it frequently in patients referred to me for other reasons.

Few psychiatric disorders have stirred up as much controversy and as many strong opinions as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), with claims that it is overdiagnosed or does not exist at all, and that children are being drugged with potentially dangerous medications for normal naughtiness or fidgetiness so as not to inconvenience teachers and parents. Factors that would seem to lend credence to the claim that ADHD is not a real disorder are the fact that (like almost all psychiatric disorders) the diagnosis is made purely by clinical impression, as there is no definitive biological test—or even a definitive cognitive test—for its diagnosis, and the symptom criteria can be interpreted quite broadly to apply to a large proportion of people.

ADHD is defined by doctors as a neurodevelopmental disorder, but the specific causes are still debated. It is usually seen in early childhood, though it is often only diagnosed later. It is thought to be a lifelong disorder, with over 50% of children and adolescents with the diagnosis continuing to have significant and impairing symptoms in adulthood. The prevalence of ADHD is estimated to be about 5-10% for children and adolescents and 2-5% for adults.1

When inattention and hyperactivity first came to be viewed as a disorder

In 1798 the Scottish physician Sir Alexander Crichton described in detail a “disease of attention, if it can with propriety be called so” characterized by an “incapacity of attending with a necessary degree of constancy to any one object.”2 In 1902 the English pediatrician Sir George Frederic Still described a number of children in his clinical practice who had serious problems with sustained attention. Most of Still’s cases were reported to be quite overactive, and many were aggressive and resistant to discipline. All showed little “inhibitory volition” (self-control) over their behavior.3

From 1917 to 1928, the encephalitis lethargica epidemic spread around the world and affected approximately 20 million people. Many of the affected children who survived this brain infection subsequently displayed significantly abnormal behavior, which was referred to as “postencephalitic behavior disorder.” This quite often included hyperactivity and distractibility. These children were disruptive in their behavior in school. Postencephalitic behavior disorder aroused interest in hyperactivity in children and influenced the scientific development of the concept that became ADHD—especially the observation that hyperactivity and distractibility could be caused by brain damage.4

Stimulants found to be effective in treating hyperactivity and inattention

In 1937, Charles Bradley, medical director of a hospital treating neurologically impaired children in Rhode Island, reported a positive effect of the stimulant medicine benzedrine5 on motivation, learning, and behavior in children with various behavior disorders. Some of these children would possibly be diagnosed with ADHD today (others had definite neurological disorders or residual effects of encephalitis).6 Bradley later identified children who were most likely to benefit from benzedrine treatment as characterized among other things by short attention span, hyperactivity, and impulsiveness.7

Minimal brain dysfunction and hyperactivity

Influenced by postencephalitic behavior disorder, in the 1940s through the 1960s the cluster of symptoms that we now think of as ADHD came to be referred to as minimal brain damage, a term later softened to minimal brain dysfunction. The assumption was that there was some form of subtle brain damage incurred either in childhood or during the birth process, even in the absence of neurological symptoms. Attempts were made in the 1950s to define the syndrome more specifically, and the name “hyperkinetic impulse disorder” was suggested. Hyperactivity was considered the most striking feature of the disorder.8

In 1960–1961, Ritalin, the trade name for methylphenidate, which had been synthesized in 1944, was approved for prescription by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Ritalin began to be marketed heavily for hyperactive children.9

A shift in emphasis from hyperactivity to inattention

In the 1970s, further research in children with this disorder led to a shift in emphasis from hyperactivity to attention deficit, and toward the beneficial effects of stimulants on inattention. In 1980, with the publication of DSM-III, the disorder was renamed attention deficit disorder (ADD). Hyperactivity was no longer considered an essential criterion for the disorder, which could be diagnosed “with or without hyperactivity.”10

In 1994. DSM-IV was published and kept the diagnostic category of ADHD but added three subtypes: predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive, and combined.

In the 1990s, the disorder came to be regarded as not just a deficit of attention, but a more general weakness of executive function or cognitive control (which includes, among other things, attentional control, inhibitory control, and working memory).11 These cognitive functions are important for such things as goal-directedness, self-control, and organization. Motivational deficits and deficits in brain reward/reinforcement mechanisms also came to be seen as part of the disorder.

It was also recognized in the 1990s that ADHD was not exclusively a childhood disorder that resolves with age, but rather a chronic, persistent disorder continuing into adulthood in many cases (though it does seem to improve in adulthood in some people).

Biological findings

Research into the biological underpinnings of ADHD also increased in the 1990s and 2000s. Structural and functional brain imaging studies identified specific neural abnormalities in ADHD.12 Several genetic associations were identified for the disorder, which had been shown from family, twin, and adoption studies to be strongly heritable. People with ADHD were found to have underactivity of dopamine in their brains, which fits with the theory that their brains are “understimulated” or underaroused, requiring higher levels of external stimulation and novelty to activate their attentional and reward systems.13, 14

In 2013, the DSM-5 was published and kept the same symptoms as those in DSM-IV but slightly lowered the threshold for making the diagnosis, in both children and adults.

Increase in diagnoses and stimulant prescriptions

In the 1990s there was an at least three-fold rise in stimulant prescriptions in the United States, primarily to treat children with ADHD.15 This was partly due to the disorder becoming better understood and more generally accepted within the medical and mental health communities.

In the early 2000s, several long-acting forms of stimulants,16 such as Concerta, Adderall XR and Vyvanse, were introduced and heavily marketed.17 The National Survey of Children’s Health revealed that 9.5% of American youth aged 4–17 had received a diagnosis of ADHD as of 2007, with two-thirds of the diagnosed group receiving medication.18

Criticism and concern

As ADHD diagnoses and stimulant prescriptions increased, public doubt increased regarding the validity of the diagnosis and the justifications for treatment. Critics argued that ADHD is an unnecessary medicalization of children who are not ill but who simply display challenging behavior.19 Some argued that the diagnosis was invented or greatly expanded purely to serve the financial interests of drug companies.20

One End of a Normal Continuum

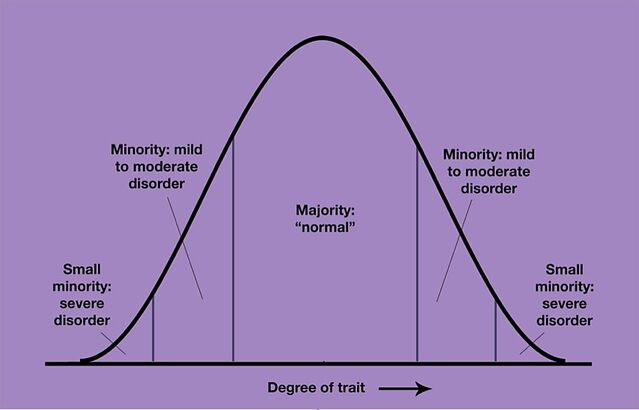

A big part of the problem in the debate is the binary view (reinforced by the categorical approach of the DSMs) that ADHD is a “thing” that you either have or do not have. It probably makes far more sense to conceptualize it as one end of a continuum of traits defining the general population:21

The trait on the X-axis of the graph would be attention span, or perhaps more broadly, executive function. Thus, the left end of the curve would represent people with ADHD. This model can be applied to other mental disorders, too; the trait on the X-axis could just as well be anxiety.22

There is in fact considerable evidence for ADHD being one end of a continuum rather than a discrete entity.23 Even the brain imaging and genetic findings associated with ADHD are consistent with a continuum model.24 This does not negate the distress and impairment of functioning associated with more severe symptoms,25 nor the need for and value of treatment. But it does inevitably mean that there will always be debate about what degree of symptoms (or perhaps we should say of traits) warrants treatment. It also means that the “treatments” can legitimately be understood as performance enhancers, improving the functioning of individuals with a short attention span.

A continuum model explains why the threshold for diagnosis is fluid. It becomes clear how the threshold might have decreased with time, as society changed in the direction of increasing demands in school and job performance. The structure of schools, and of many modern occupations, favors individuals who are more able to sustain effortful focus and attention to detail for low-stimulation tasks that require quiet patience, persistence, organization, self-discipline, and the ability to work towards very delayed or abstract rewards.

Evolutionary mismatch

The environment created by modern societies bears little resemblance to the ancestral environment in which our species evolved for most of its history. Paleolithic hunter-gatherer groups probably benefited as much from quick-thinking exploratory risk-takers—adventurous novelty-seekers who swiftly got the gist of their surroundings, made snap decisions, had quicker responses to predators, and were eager to migrate,26 as they did from the tribesmen who noticed and were interested in the small details—such as the trackers who meticulously and patiently studied the prey’s hoof prints to deduce the animal’s type, size, age, health, and time of transit.27

It is unlikely that the "disorder" of ADHD would be as prevalent in the human species if it were not maintained by evolutionary selection pressures that conveyed certain advantages to some of its characteristics or associated traits.28

Not just another psychiatric disorder

The traits that define ADHD—focus, cognitive control, inhibitory control (self-control), and sensitivity to reward (which drives motivation)—are traits that are fundamental to human functioning. ADHD can be understood as one end of a spectrum of normal, centrally important human traits. A large swath of the population find themselves disadvantaged by evolutionary mismatch in our highly structured society. Seen this way, ADHD is not just one among many specific kinds of psychiatric disorders (in the DSM, ADHD is listed as one of a large number of categorical mental disorders). Rather, it makes more sense to view it as one end of a continuum of a set of centrally important cognitive and behavioral traits that underlie and determine many aspects of human functioning.29

References

1. See for example the National Institute of Mental Health's statistics on ADHD, or the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 2018 ADHD guidelines or the Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance (CADDRA)'s ADHD Practice Guidelines, 2018. Rates of diagnosis have been going up, especially in the U.S. The NIMH reports that the prevalence of children ever diagnosed with ADHD increased by 42% between 2003 (7.8%) and 2011 (11.0%). ADHD is diagnosed in more than twice as many boys as girls (15.1% vs. 6.7% in the U.S. in 2011), but it tends to be under-recognized in girls, who tend to be less disruptive than boys. It may also be under-recognized in adults. More conservative estimates put the overall prevalence of more strictly defined ADHD in children at 3-5%, and still lower (1-2%) when diagnosed with the WHO’s more restrictive ICD-10 criteria. Much of the controversy about diagnosis centers on the less severe cases and their overlap with what might be regarded as normal traits and behaviors. As one highly influential article critical of the increasing rates of diagnosis and treatment (and the influence of pharmaceutical company marketing) in the U.S. put it: “Although proper A.D.H.D. diagnoses and medication have helped millions of children lead more productive lives, concerns remain that questionable diagnoses carry unappreciated costs."

2. He added: “When people are affected in this manner, which they very frequently are, they have a particular name for the state of their nerves, which is expressive enough of their feelings. They say they have the fidgets.” [a reprint of his 1798 book chapter can be found in: Crichton A. (2008). An inquiry into the nature and origin of mental derangement: on attention and its diseases. Journal of attention disorders, 12(3), 200–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054708315137.] There was an even earlier description of an ADHD-like syndrome by a renowned German physician, Melchior Adam Weikard, in 1775 [Barkley, R. A., & Peters, H. (2012). The earliest reference to ADHD in the medical literature? Melchior Adam Weikard's description in 1775 of "attention deficit" (Mangel der Aufmerksamkeit, Attentio Volubilis). Journal of attention disorders, 16(8), 623–630. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054711432309]. Also of interest in the history of ADHD, in 1844 the German physician Heinrich Hoffmann created an illustrated children’s story including “Fidgety Phil,” which described a naughty boy with what today might be considered ADHD.

3. He believed that these children displayed a major “defect in moral control.” He defined moral control as “the control of action in conformity with the idea of the good of all.” [Barkley, R. A., & Peters, H. (2012)]. He agreed with William James’s notion that failure of volitional control is fundamentally an attentional problem. Being unable to hold an idea for a particular course of action clearly in mind, the child is at the whim of stimuli promising immediate gratification. Still observed that both parents and teachers commonly noted inattention as a significant behavioral problem. Many of Still’s patients had either a history of retardation or physical disease affecting their brain, but a number of them did not have any such history. [Connors, K: From the Editor. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2000; 3(4):173-191. https://doi.org/10.1177/108705470000300401]

[CLICK 'MORE' TO VIEW FOOTNOTES 4-29]

4. Lange, K. W., Reichl, S., Lange, K. M., Tucha, L., & Tucha, O. (2010). The history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorders, 2(4), 241–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-010-0045-8

5. Modern pharmacological treatments for ADHD are mostly stimulants. At the risk of oversimplification, you could think of these stimulants as similar to caffeine, but stronger and more effective.

6. [Bradley, 1937, cited by Lange et al. (2010)] This was a chance finding—the stimulant was given to the children for other medical reasons but was noticed to lead to a striking improvement in behavior and school performance in many of them. In addition, some decrease in motor activity was usually noted in the children, who also “became emotionally subdued without, however, losing interest in their surroundings.” The seemingly paradoxical effect of a stimulant subduing hyperactive behavior was attributed to the drug stimulating the higher inhibitory regions of the brain, thereby increasing the inhibition of behavior. We now have a better understanding of the circuitry and mechanisms, but this was more or less a correct understanding. Stimulants also directly stimulate attention and reinforce motivation.

7. Despite Bradley’s finding, stimulant prescriptions for hyperactive / inattentive children did not really increase in the next 25 years or more, perhaps partly because the syndrome was not yet clearly defined and named, and perhaps also due to the influence of psychoanalysis at that time.

8. In 1968, the second edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-II) renamed it “hyperkinetic reaction of childhood” (The APA was at that time heavily influenced by psychoanalytic thinking, which tended to assume that mental disorders were reactions to childhood psychological trauma or parent-child relational issues). Hyperkinetic reaction of childhood was defined as being characterized by overactivity, restlessness, distractibility, and short attention span, and was thought to be mostly a problem in young children.

9. Stephen Hinshaw and Richard Scheffler, The ADHD Explosion: Myths, Medication, Money, and Today's Push for Performance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), Kindle Edition, p. 5. The amphetamine stimulant dextroamphetamine (trade name: Dexedrine), which had been around since the 1930s, was also being marketed and prescribed for hyperactivity and inattention in the 1970s.

There is a very interesting, revealing and concerning parallel history from the 1930s through the 1960s of widespread non-medical use / misuse of stimulants in the military (particularly in Nazi Germany, to power the blitzkrieg), in general culture (particularly in the U.K. and U.S., including among artists and scientists, to enhance creativity and productivity), as weight-loss medications and attempts to treat depression, in what in America has been called the First Amphetamine Epidemic.

10. In contrast to the criteria for ADD in the DSM-III (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, third edition), the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases, ninth edition (ICD-9) continued to focus on hyperactivity as necessary for the diagnosis, calling it hyperkinetic disorder. This continued in ICD-10 but is changing in ICD-11.

11. Some studies suggested that not all children with ADHD had deficits of executive function—but it partly depended on how these were defined and measured.

12. The cerebral cortex, particularly the frontal cortex (and prefrontal-striatal circuitry), has been found to be thinner in individuals with ADHD. One study in children suggested that this is merely a developmental lag, whereas other studies in adults (e.g. here and here) suggested persisting deficits.

13. In 2009, an important research paper was published by Nora Volkow and colleagues showing reduced dopamine receptors and dopamine transporters in the brain’s reward pathway in adults with ADHD. These research subjects had never been medicated for their ADHD, so medication effects could not have been the cause. This paper revived the idea that patients with ADHD may have reward and motivation deficits, not just inattention and low inhibitory control. [Volkow, N. D., Wang, G. J., Kollins, S. H., Wigal, T. L., Newcorn, J. H., Telang, F., Fowler, J. S., Zhu, W., Logan, J., Ma, Y., Pradhan, K., Wong, C., & Swanson, J. M. (2009). Evaluating dopamine reward pathway in ADHD: clinical implications. JAMA, 302(10), 1084–1091. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1308]. Nora Volkow is a research psychiatrist and Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

14. Stimulant medications increase the level of dopamine transmission and hence the brain’s sensitivity to external stimuli and reward, thereby having a focusing and motivating effect. They basically make otherwise uninteresting stimuli and boring tasks more engaging to the brain. Via these primary effects they have their secondary effects of reducing ADHD behaviors such as bored stimulus-seeking, novelty-seeking, impatience, restlessness, hyperactivity, and impulsivity.

15. Hinshaw and Scheffler, The ADHD Explosion, p. 7.

16. The effects of these medications last for up to 12 hours, compared with 3-4 hours for Ritalin and 5 hours for the other older short-acting stimulant, Dexedrine.

17. These new drugs were significantly more expensive than off-patent Ritalin and Dexedrine. Naturally, pharmaceutical companies aggressively marketed their new drugs, including encouraging doctors to recognize and diagnose ADHD more often.

18. Hinshaw and Scheffler, The ADHD Explosion, p. 9. In 2016, 9.4% had received the diagnosis according to this survey, suggesting that the increase might have plateaued (https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/data.html and https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/timeline.html)

19. Alternatively, it has been argued that ADHD is not a disease as such but rather a cluster of non-specific symptoms that are a final common behavioral pathway for a range of emotional, psychological, and/or learning problems.

20. Drug companies have also been criticized for downplaying the risks of stimulant medications. And there has been increasing concern about rising rates of inappropriate stimulant prescriptions in young adults who seek them as performance enhancers and who don’t necessarily need them. There have been alarming reports in the media of stimulant dependence, of stimulants causing serious adverse effects with tragic consequences, and of the general trend toward overuse of stimulants as performance enhancers.

21. On a bell-curve, just as when describing the population according to any other normally distributed trait, such as IQ, height or blood pressure.

22. The model implies that traits at the opposite end of the curve are also dysfunctional. And indeed, being excessively focused (and excessively self-controlled), or for that matter, being too low in anxiety, are very much associated with dysfunction and with psychiatric disorder.

23. McLennan J. D. (2016). Understanding attention deficit hyperactivity disorder as a continuum. Canadian family physician, 62(12), 979–982. https://www.cfp.ca/content/62/12/979.full

24. Faraone, S. V., & Larsson, H. (2019). Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Molecular psychiatry, 24(4), 562–575. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0070-0

25. As the continuum / bell-curve model implies, ADHD may simply be the statistical result of the way the genetic “cards” are “dealt.” While this may be the case for most individuals who meet criteria for ADHD, it is also possible that in some other cases—particularly those with more severe symptoms, ADHD may be the result of specific pathological causes. This is also what we see in intellectual disability: most people who score low on IQ simply got dealt a bad hand, and are quite likely to have inherited this trait from their parents, who may themselves score relatively low on IQ. But some individuals with low IQ, particularly the more severely affected, have specific causes for their disability, such as chromosomal disorders, metabolic disorders, or brain damage sustained at birth. To be clear, we are talking about IQ here simply as an analogy: to consider how ADHD, like low IQ, could represent one end of a normal continuum, described by a bell-curve, and yet might in addition sometimes be caused by specific diseases. It is noteworthy in this regard that certain non-genetic biological factors have been linked to an increased risk of ADHD: low birth weight, heavy maternal alcohol use during pregnancy, maternal smoking during pregnancy, and lead levels. It is also noteworthy that there is a significant comorbidity (co-occurrence) of specific learning disabilities (e.g. dyslexia, dysgraphia, auditory processing disorder) with ADHD—anywhere from 30 to 50 percent, according to some estimates.

26. There is in fact a very interesting finding showing an association between ancestral migration distance of different human populations across the globe and a genetic marker for a certain kind of dopamine receptor that is associated with novelty-seeking ADHD traits [Matthews, L. J., & Butler, P. M. (2011). Novelty-seeking DRD4 polymorphisms are associated with human migration distance out-of-Africa after controlling for neutral population gene structure. American journal of physical anthropology, 145(3), 382–389. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.21507]

27. You might wonder why evolution would favor extreme traits—the tail ends of the bell curve. I addressed this in an earlier post:

Statistically, some individuals in every generation will inherit more extreme versions of traits at either end of the spectrum. While extremes of a trait might seldom be advantageous, they are an inevitable statistical result of genetic diversity, and that diversity is certainly adaptive for the species as a whole. You can’t have a bell curve distribution of traits without the two extremes or “tails” of the curve.

From an evolutionary point of view, it is possible that in certain situations ADHD traits may have been beneficial to society as a whole, by increasing reproductive fitness and adding diversity to the gene pool, despite being detrimental to the individual.

28. Jensen, P. S., Mrazek, D., Knapp, P. K., Steinberg, L., Pfeffer, C., Schowalter, J., & Shapiro, T. (1997). Evolution and revolution in child psychiatry: ADHD as a disorder of adaptation. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(12), 1672–1681. (Dr. Peter Jensen was at that time Chief of the Child and Adolescent Disorders Research Branch, National Institute of Mental Health). See also here and here, for other examples of articles exploring evolutionary explanations for ADHD.

29. This way of understanding ADHD also fits with the National Institute of Mental Health’s Research Domain Criteria (RDoC), a long term project attempting to ultimately devise a framework for understanding mental disorders that will be fundamentally different from the current symptom-based DSM categories. The RDoC approach is based on underlying brain processes, and it conceptualizes mental disorders dimensionally (i.e. on continua) rather than categorically as discrete entities. As their website explains: “RDoC is a research framework for investigating mental disorders. It integrates many levels of information (from genomics and circuits to behavior and self-report) to explore basic dimensions of functioning that span the full range of human behavior from normal to abnormal.” A look at the RDoC matrix shows that ADHD traits include several central dimensions of brain functioning, including reward responsiveness, attention, and cognitive control (and often working memory too).

Another fundamental way of understanding human behavior is the Five Factor Model of Personality. According to this model, there are five fundamental factors / dimensions describing human personality (much of which is determined by inborn temperament). The general population is distributed on a bell-curve for each of these five factors / dimensions. Extreme traits at either end of a dimension, i.e. at the left or right hand tails of the bell curve, are maladaptive. ADHD maps onto the left-hand side of the curve for one of the five fundamental factors: the factor referred to as conscientiousness (which is further defined by a number of traits). For more explanation, see my blog post “What Makes Some People So Motivated and Self-Controlled?” Once again, we see according to this model that ADHD is not just one among a large number of very particular kinds of psychological difficulties that people can have, but rather can be better understood as one end of a continuum of an over-arching set of centrally important traits—among just a few fundamental sets of traits defining humans.