Suicide

Why Many Who Attempt Suicide Do Not Have Active Suicidal Thoughts

Some pathways to suicide involve no ideation at all.

Posted July 14, 2022 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- It is commonly assumed that suicidal ideation intensifies gradually before a suicide attempt or death occurs.

- A new study shows that some suicides don't involve worsening ideation—or any suicidal thoughts at all.

- In the study, one in ten lifetime suicide attempters never experienced suicidal ideation.

Each year, nearly 800,000 people die from suicide. Though suicide is more prevalent in some countries (e.g., Guyana), among certain groups (e.g., middle-aged Caucasian men in the U.S.), and at certain times—in spring and summer, in the first week of a month, earlier in the week, and during afternoons—it can happen any time or place.

Several risk factors for suicide have been identified. These include male gender, Caucasian ethnicity, mental illness (particularly depression), psychiatric symptoms (hopelessness, impulsivity), physical or sexual abuse, loneliness, relationship conflict, financial difficulties, access to weapons, and personal history of suicide attempts.

Another risk factor is suicidal ideation (i.e. having thoughts about ending one’s life). However, a recent study by Wastler and colleagues suggests that although “some individuals who attempt suicide experience progressively worsening suicidal thoughts,” others experience only passive ideation, and some have no suicide‐related thoughts at all. The paper, published in the June issue of the Journal of Clinical Psychology, is reviewed below. (Note: Passive ideation refers to thoughts such as "I wish I could disappear.” An example of active ideation is "I should kill myself.”

Investigating the Link Between Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempts

Sample: 6,200 American adults; 51.0 percent females; 62 percent Caucasian; 41 percent between 25 and 44 years old; 45 percent with a college education.

Measures

The Self‐Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview‐Revised (SITBI‐R) was used to assess passive and active suicidal ideation. Specifically, participants were asked if they had any of these thoughts before:

- I wish I could disappear or not exist.

- I wish I could go to sleep and never wake up.

- My life is not worth living.

- I wish I was never born.

- I wish I were dead.

- Maybe I should kill myself.

- I should kill myself.

- I am going to kill myself.

To assess suicidal behavior, participants were asked if they had done any of the following:

- Purposefully hurt yourself without wanting to die.

- Been very close to killing yourself, but at the last minute you decided not to do it before taking any action.

- Been very close to killing yourself but at the last minute, someone or something else stopped you before you took any action.

- Started to kill yourself and then you stopped after you had already taken some action.

- Started to kill yourself and then you decided to reach out for help after you had already taken some action.

- Tried to kill yourself and someone found you afterward.

- Tried to kill yourself and no one found you afterward.

Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS). Participants answered to what degree they had experienced, in the previous week, positive feelings (active, alert, attentive, determined, inspired) and negative feelings (afraid, ashamed, hostile, nervous, upset).

Results

Here are some key findings:

- “The sole presence of passive suicidal ideation was associated with increased rates of both lifetime and past‐month suicide attempts.”

- “One‐third of individuals with a lifetime suicide attempt denied ever experiencing active suicidal thoughts in their lifetime and one in 10 denied ever having any suicide‐related thoughts.”

- “Half of the individuals with a recent suicide attempt denied experiencing active suicidal thoughts during the month they attempted suicide. One in five denied experiencing any suicide‐related thoughts during the month they attempted suicide.”

What these findings indicate is that the progression from suicidal thoughts to suicidal behaviors does not always involve the continuum model pathway of passive thoughts of death intensifying and resulting in more active thoughts, planning, attempt, and finally, death.

So, some people appear to “skip” stages of the continuum model (e.g., no passive or active ideation before a suicide attempt).

Takeaway

It is commonly assumed that suicide risk occurs on a continuum, meaning thoughts of death gradually intensify before a suicide attempt or death by suicide occurs. But is this true for everyone? No, according to the findings of the current study.

For instance, analysis of data showed that one in ten lifetime suicide attempters never experienced suicidal ideation—and more than a fifth of those who attempted suicide in the previous month had not experienced suicidal ideation at all during that period.

So, it appears suicidal behavior can occur without suicidal ideation. How?

Perhaps, the authors suggest, past suicide planning is “stored on a ‘mental shelf,’ which can be easily accessed and acted upon without current suicidal thoughts.”

Other possibilities include unplanned or impulsive suicidal behaviors. Or suicide attempts that occur after negative and distressing thoughts (e.g., feeling unworthy of love, feeling unable to tolerate a situation), as opposed to after suicidal ideation.

An implication of the findings is that we need to ask about both passive and active suicidal ideation in suicide risk assessment, but also to remember that some people who attempt suicide may have experienced neither.

If you or someone you love is contemplating suicide, seek help immediately. For help 24/7 dial 988 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, or reach out to the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741. To find a therapist near you, visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

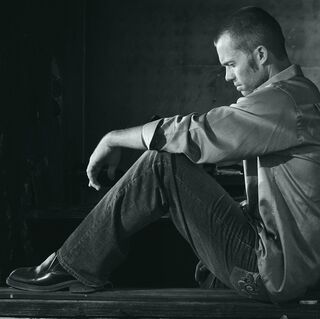

Facebook/LinkedIn image: antoniodiaz/Shutterstock