Anxiety

Are the Socially Anxious Good or Bad at Reading Minds?

A new study investigates two theories of social anxiety in children.

Posted September 17, 2019 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Relationships become more important to children as they grow up—especially as they enter adolescence. During this period, they regularly worry about being negatively evaluated by their peers (e.g., embarrassed, humiliated, and rejected). Some become so severely anxious that they meet the criteria for social anxiety disorder (aka social phobia).1

There is disagreement as to whether socially anxious children are great or terrible at mindreading—reading people’s feelings and/or thoughts, based on available cues like an individual’s facial expression or gaze. A study, published in the July issue of Child Development, investigates this question.2

The question concerns two theories which have been used to explain the mind-reading abilities of socially anxious children.

- The “sociocognitive deficit theory” suggests that socially anxious children, compared to mentally healthy children, have a poorer understanding of other people’s mental states. These children find social interactions unpredictable and confusing; therefore, they feel anxious in social situations.

- A lesser-known theory, the “advanced sociocognitive ability theory,” suggests the opposite, saying that socially anxious children have greater mindreading abilities compared to others. So why do they feel anxious? Because these advanced mindreading abilities, despite their benefits, are associated with a heightened awareness of and sensitivity to being evaluated by others. Such awareness results in greater self-consciousness and social anxiety.

The study reviewed below was a test of these two theories.

An investigation of mindreading abilities in socially anxious children

The sample consisted of 105 8- to 12-year-old children (44% boys) recruited from schools in the Netherlands. To participate in this investigation, these students were asked to come to the lab with their parents. In 77% of cases, they came with their mothers.

The child-parent duos then completed the Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory. A sample item from the child version of this inventory reads, “I feel anxious when I am with other girls, boys, or adults and I am in the center of attention (when everyone is looking at me).” The parental version reads, “My child feels anxious when she or he is with other girls, boys, or adults and she or he is in the center of attention (everyone is looking at her or him)” (p. 1428).2 The child and parental reports were correlated: r(95) = 0.5, p < 0.001.

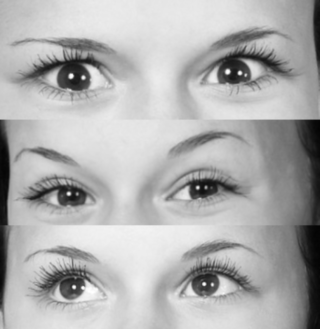

Subsequently, children completed a mindreading task called Reading the Mind in the Eyes Task. Each child sat in front of a computer screen and looked at 28 black and white pictures of eye regions showing different emotions and states of mind—interested, sad, angry, etc. (The three examples in the picture below are not from the actual test).

Each picture was presented with four statements, only one of which was a correct description of the feeling or state of mind portrayed in the photo. Mindreading ability was calculated based on the number of correct answers.

Next, children completed a task designed to provoke social anxiety: They were asked to perform their favorite song on the podium in front of a camera which supposedly recorded their performance for a “professional singer” to evaluate later.

The children’s blushing response during the first 30 seconds of this minute-long task was measured with a thermometer and a photoplethysmograph—which measured blood pulse amplitude through sensors that were attached to the children’s cheeks before the performance began.

Good or bad at mindreading?

Results showed that both poor and advanced mindreaders were more likely to be socially anxious than healthy children, though social anxiety was highest in poor mindreaders.

These findings provide support for the existence of two pathways to social anxiety in children. One pathway, as noted earlier, involves mindreading deficits, meaning misinterpreting social signals—remarks, looks, and other behaviors—as necessarily critical.

To reduce their anxiety, children with deficits in mindreading often avoid social situations. But doing so has negative consequences. For instance, avoiding social situations results in fewer opportunities to practice and improve one’s ability to read people’s minds.

The present findings also supported the theory that social anxiety arises through a second pathway, that of advanced mindreading. Of course, advanced mindreading abilities are often socially adaptive because being attuned to cues in social situations helps bonding and cooperation. However, these abilities also allow greater awareness of being evaluated by others, which increases self-consciousness.

And self-consciousness—being associated with blushing and other physiological reactions—results in discomfort in social settings and avoidance of social situations.

In this study, the skilled mindreaders who did not blush (and presumably did not feel self-conscious) showed less social anxiety. Therefore, self-consciousness seems to be a major link between advanced mindreading ability and the experience of social anxiety.

In summary, this investigation’s findings suggest that both advanced and poor sociocognitive abilities might have a negative impact on children’s social life, resulting in fear, discomfort, and avoidance of social situations. That is why, the authors note, prevention and early interventions are important: “For children with deficits in mindreading, these [prevention] efforts may focus on enhancing sociocognitive abilities, whereas for children with advanced mindreading, they may focus on tackling the excessive mindreading and dealing with heightened self-consciousness and sensitivity to others’ opinions” (1438).2

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: Author.

2. Nikolic, M., van der Storm, L., Colonnesi, C., Brummelman, E., Kan, K. J., & Bögels, S. (2019). Are socially anxious children poor or advanced mindreaders? Child Development, 90(4):1424-1441.